Art exhibit on Northeastern’s Oakland campus honors legacy of a renowned and beloved professor — and her living students

When internationally acclaimed artist Hung Liu asked the art museum on Northeastern’s Oakland campus to showcase the work of 13 of her female students with a special exhibit, Liu’s magnanimity came as no surprise.

“She was very, very generous” and a wonderful mentor, says MCAM Director Stephanie Hanor, who knew Liu as a tenured art professor.

Sadly, Liu never got to see the exhibit featuring her former students come to fruition.

She was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer a couple of months after the conversation with Hanor and died two weeks later on Aug. 7, 2021, to the shock of the art world and the Oakland community.

Now the art museum is honoring both Liu’s request and her memory with an exhibit called “Look Up to the Sky: Hung Liu’s Legacy of Mentoring Women Artists.”

Although Liu wanted the focus to be on her students, the exhibit running through March 24 also features three of Liu’s works, including “White Rice Bowl,” an 80-by-80-inch painting Liu gave to the museum that’s being showcased for the first time.

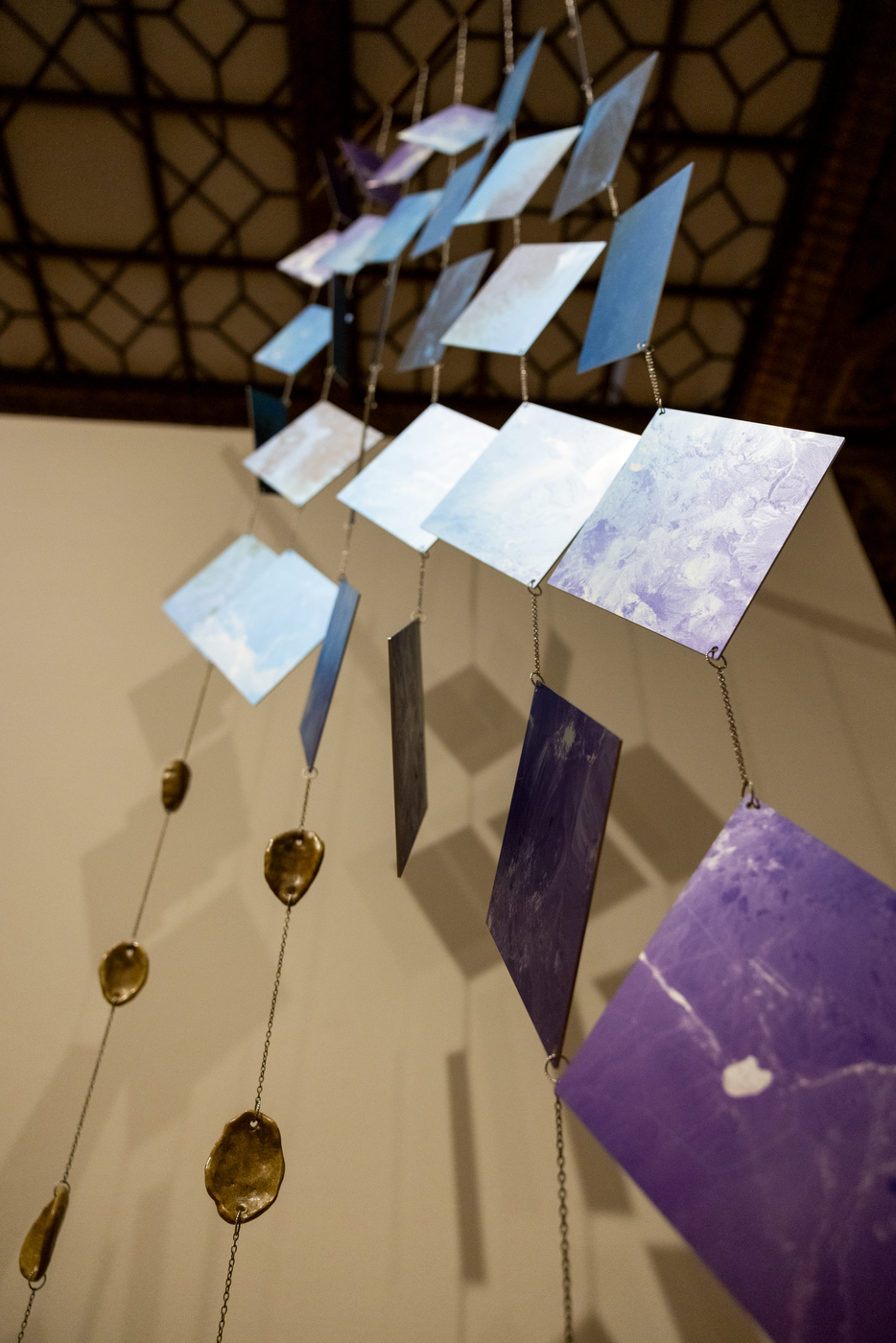

Photos by Ruby Wallau for Northeastern University

“We put Hung’s work in the center of the museum, and everybody else sort of radiates out from her,” Hanor says.

“In her version, I don’t even know that her work would have been included,” Hanor says. “But because she passed away so suddenly, it made sense to include work by Hung.”

The featured artists, who range in age from their 30s to their 80s, all passed through the college’s MFA program and were instructed by Liu.

“Hung would have been the first to say that she has really great former students who are men, but she really, really wanted this particular exhibition to be about the women,” Hanor says.

“For women, it’s much harder to get a gallery, to have shows, to be collected. Your work sells for less,” Hanor says, adding that Liu was known for advancing her students’ careers by introducing them to curators and gallerists and hiring them as assistants.

Liu’s experience growing up in Maoist China and doing years of hard farm labor as a young woman before being trained as a muralist and coming to the United States for art school also informed her empathy for individuals who struggle to be seen and acknowledged.

“She’s coming from this experience of being an immigrant artist from China to the U.S. in the 1980s, kind of finding her own way as a woman of color within that art world,” Hanor says.

Born in 1948 in Changchun, China, a year before the People’s Republic of China was created, Liu lived through the totalitarian extremes of the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution.

Her father was sent to a labor camp, and Liu did not see him for 50 years, according to a posthumous profile in ARTNews.

o by Ruby Wallau for Northeastern University

13 women students she mentored in Oakland. Photos by Ruby Wallau for Northeastern University

Liu’s own years at an agrarian re-education camp were followed by art school in China. In 1984, she made her way to California to study art, and within four years had begun two of her best known works, “Where is Mao?” and “Resident Alien,” the latter of which “re-created her own green card as a painting,” according to ARTNews.

“She was one of the first Chinese artists to come over to the U.S. and make her career here,” Hanor says.

Liu based many of her large-scale linseed oil paintings on Chinese vintage photographs as well as Dust Bowl photos taken by Dorothea Lange. Her works depict Depression-era mothers, hungry children and Korean “comfort women” trafficked during World War II.

“The content of her work was very much about championing voices that are typically excluded,” Hanor says.

“She was very much a figurative artist, working from historical photographs, interested in people and populations whose stories were not told in history and certainly not in art museums,” she adds.

The large scale of Liu’s paintings “helps give a kind of grandeur” to the individuals pictured, she says.

Liu also created public art installations, including a glass window wall at Oakland International Airport bearing images of 80 red-crowned cranes in flight.

“She does use traditional Chinese symbols in her work. She’s very much bridging this experience of being Chinese in America,” Hanor says.

Liu, who died at age 73, moved to northern California in 1990 and was a tenured professor at Mills for more than 20 years.

Still considered the most prominent female Chinese-born artist in the U.S., Liu’s work was exhibited posthumously at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., in 2022 and can be seen at the National Museum of Women in the Arts through Oct. 20.

Monica Lundy, a former Liu student whose works are included in the current exhibition, told KQED radio in 2021 that her professor “was generous and nurturing, yet firm and exacting.”

Lundy’s own works include mixed-media paintings of women unjustly institutionalized during Benito Mussolini’s regime.

The art included in the MCAM exhibition also includes oil paintings of underwater scenes by Bambi Waterman and a silkscreen by Yoshiko Shimano honoring Kiev.

“It’s been really fun to work on this show because it’s a wide range of types of art represented through (Liu’s) students,” Hanor says, adding that the featured artists have achieved considerable success.

“The through line for all the artists was that Hung was an incredibly hard worker. If she wasn’t in the classroom, if she wasn’t out in the art world doing that work, she was in her studio, all the time painting, painting, painting, painting. And all these students have that incredible work ethic.”

The other featured artists are Rosana Castrillo Diaz, Nicole Fein, Danielle Lawrence, Nancy Mintz, Sandra Ono, Susan Preston, Mel Prest, Rachelle Reichert, Gina Tuzzi and Lien Truong.

A curator-led tour of the exhibit will be held from 3 to 4 p.m. March 23. A 3-D virtual tour of the exhibition is available on the museum’s website.