Is AI the future of standup comedy? An AI George Carlin standup special says otherwise

Amid concerns about human artists being replaced by AI, experts say the hour-long special showcases the limits of AI –– and humanity’s fear of letting anything truly die.

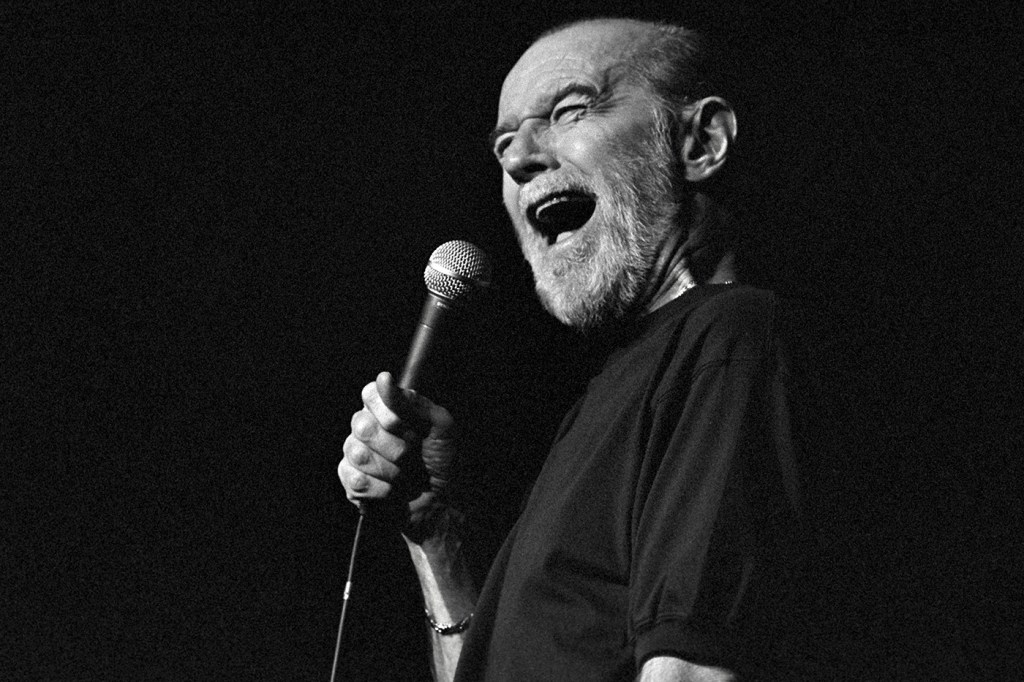

Comedian George Carlin recently dropped his first new standup comedy special in 16 years. It came as a surprise to his hardcore fans and even his family, considering the comedian died in 2008.

Generated by Dudesy, an AI that “hosts” the Dudesy podcast alongside comedian Will Sasso and podcaster Chad Kultgen, the hour-long special, “George Carlin: I’m Glad I’m Dead,” attempts to resurrect the late comedian to offer his thoughts on contemporary topics like social media, mass shootings, Taylor Swift –– and AI. It almost immediately sparked pushback from fans and the general public, including Kelly Carlin, the comedian’s daughter.

The conversation about how AI will be used ethically in the arts and beyond has been swirling since the technology started to become more publicly available over the last few years with tools like ChatGPT and DALL-E. But the AI Carlin standup special added fuel to the fire, bringing up concerns about whether AI will replace human artists.

So, is AI Carlin a sign of things and that the future of standup comedy will really be just an array of AI-generated ghosts of comedians past?

According to Michael Ann DeVito, an assistant professor in Khoury College of Computer Sciences at Northeastern University, we’re a long way off from that ever being a reality. If anything, the Carlin special proves the limits of AI, she says.

“On a technical level, there is no additional creativity whatsoever, and you can actually see that in the performance that this thing puts out,” DeVito says.

Dudesy, the AI behind the special that is operated by a company that remains nameless, likens its AI Carlin to an impression at the beginning of the special. It claims “it listened to all of George Carlin’s material and did my best to imitate his voice, cadence and attitude as well as the subject matter I think would have interested him today.”

DeVito says the AI Carlin likely correctly guesses Carlin’s views on most of the issues tackled in the special, in part because of how outspoken Carlin was. It also nails Carlin’s cadence, she says, because cadence is something “you can map out over the course of a conversation in numerical fashion.”

But when it gets to generating the underlying meaning of a standup comedian, there are still limits.

“[Carlin] told you this story that introduced a lot of characters in a surprising level of detail and then hit you with a hard truth that you may not have expected or, more often, didn’t want to hear and he felt you needed to hear,” DeVito says. “That can’t be replicated by the AI. That is too nuanced for the AI.”

“The structure of the special seems to be to put the headline of the take George Carlin would have produced and then follow that up with a lot of cheap shots and low-hanging fruit to justify it instead of the storytelling with the punch at the end,” DeVito adds. “It’s still getting to the same conclusions, it’s just getting there inartfully.”

DeVito says the special again raises questions about whether AI-generated art fits within existing copyright laws. In a statement released on X/Twitter, Carlin’s daughter made it clear she and her family did not sign off on the use of Carlin’s likeness. But even without that black mark against AI Carlin, there are lingering ethical and legal questions about the data being fed into these AI models that, in some cases, have been trained on illegal material.

For Cansu Canca, director of responsible AI practice at Northeastern’s Institute for Experiential AI and research associate professor in philosophy, stories like this raise a bigger question: Why?

Featured Posts

“Do we achieve anything or get anything from replicating the same artists?” Canca says. “Maybe an artist had a lot more to say, but we have absolutely no idea how they would have said it. Because their existing creative work does not necessarily tell us how the changes in the world would have affected their worldview and their perspective, we just don’t know what their take would have been if they continued to interact with the world in this bi-directional way. When we try to extend their work using AI, we are not actually hearing their individual perspective anymore, so what are we then holding on to?”

DeVito acknowledges that there are industry, market and labor driven reasons we’re getting an AI Carlin and that there are practical, impactful uses for AI. But she says this use of AI in the arts could all come back to something very simple and very human: grief, mortality and humanity’s attempt to put them in the rearview mirror. Beyond AI-generated evocations of celebrities, some people have already created AI versions of their loved ones for funerals.

“Humans since day one have been trying to figure out ways around grief because it is one of the most horrible things you have to plod through, and there’s no way to cheat grief,” DeVito says. “It’s one of the few things we’ve never figured out how to cheat. When we think about AI-generated dead people, it’s our attempt to stave off that grief, but it’s not going to work.”

What does closure look like when you never have to be without your loved ones or your favorite artists? What does letting go mean in a world where you can hear a new Carlin special every week?

“Let’s let the artist’s work speak for themselves,” Kelly Carlin wrote on social media. “Humans are so afraid of the void that we can’t let what has fallen into it stay there. Here’s an idea, how about we give some actual living comedians a listen to? But if you want to listen to the genuine George Carlin, he has 14 specials you can find anywhere.”