With Apple lawsuit looming, antitrust expert says tech giant might not fare well under the DOJ’s microscope

This year the Justice Department could launch a massive lawsuit against Apple for anticompetitive practices, according to the New York Times. But a Northeastern expert says the precedent for Apple’s behavior is well set.

The Justice Department could be nearing the launch of a massive lawsuit against Apple this year that would aim to target the tech giant’s alleged anticompetitive business practices, according to the New York Times.

The focus would be on how Apple has used its connected ecosystem of hardware and software to make it difficult for consumers to leave the Apple bubble and for other players in the industry to compete. Specifically, according to the New York Times report, Department of Justice investigators have been looking into three pieces of that ecosystem: how iMessage prevents competitors from using Apple’s messaging app; the Apple Watch and how it works better alongside the iPhone than other companies’ devices; and Apple’s payment systems that block competitors from providing similar financial services.

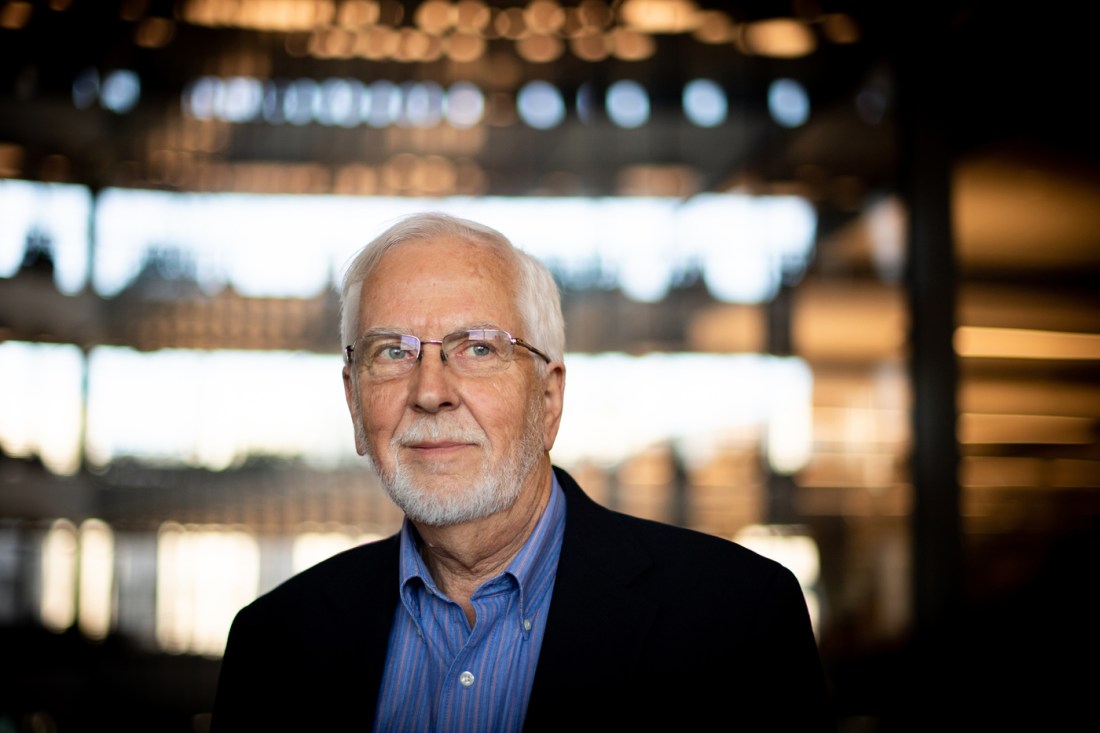

If the DOJ moves forward with its lawsuit, leading antitrust expert John Kwoka, Neal F. Finnegan distinguished professor of economics at Northeastern University, says it would be the latest domino to fall in the antitrust push against Big Tech’s biggest players. Google, Amazon and Meta, the company behind Facebook and Instagram, have all been under the antitrust microscope in the last four years.

Apple would be the biggest target yet, not only because it’s valued at $2.87 trillion but because its business model –– a “tightly integrated ecosystem” of products and services that keep customers invested, Kwoka says –– is virtually unmatched. But Kwoka says Apple is far from bulletproof.

“It’s also true that a lot of people end up paying a lot more than the cost of these goods and services and, once in, they have a tough time getting out,” Kwoka says. “It’s pretty clear Apple has a long list of potential rivals and complainants that made clear by experiences that they have been foiled in their efforts to provide alternatives to some of the package of services that Apple provides. As a result, consumers are denied some choices.”

The interlocking system of products and services Apple has created is well known for its streamlined nature and its closed-door approach involving potential competitors. In 2021, the European Commission said the company’s use of app store fees for Apple Music competitors violated its antitrust laws.

According to the Times, the scale of the DOJ’s investigation into Apple’s business practices has been sweeping. Beyond investigations into Apple Watch, iMessage and payment services, the DOJ looked into how Apple blocked cloud gaming applications, which allow people to play games by streaming them directly to their phone, on the App Store.

Editor’s Picks

Kwoka says the end result of Apple’s business model is that it offers a high-quality experience to those inside it, but it also limits consumer choice and innovation.

“This means that new products and services that might work with other parts of Apple, like the messaging service, the pay systems, and some potential innovators in that space are thwarted because they cannot access consumers,” Kwoka says.

He points to Tile, a tracking software and device company. The DOJ interviewed Tile in its investigation, and the company previously testified against Apple. In 2020, Tile claimed during congressional testimony that the tech giant hamstrung Tile’s ability to effectively operate on iPhones.

There’s a reason venture capitalists refer to the investment areas that directly compete with the Big Tech companies as the “Killzone,” Kwoka says.

“There’s evidence that VC has started to pull back on its funding for startups in the so-called Killzone where they know at the end of the day they’re simply going to get wiped out by Amazon or Facebook or Google or Microsoft or Apple,” Kwoka says.

For its part, Apple has argued that the interconnected ecosystem at the core of its business model is what makes the company competitive against its rivals. And Tim Cook, Apple’s CEO, said in testimony before a 2020 congressional antitrust committee that his company “does not have a dominant market share in any market where we do business.”

With precedent somewhat set by a 2001 antitrust lawsuit against Microsoft, Kwoka says both the DOJ and Federal Trade Commission have wisened up to this argument. It could mean Apple might not fare well under the DOJ’s microscope.

“Even if there was some truth to that, the point is it’s not product by product that one ought to look at these strategies and practices,” Kwoka says.

“The agencies are much more attuned to the complicated ways that these large companies with big footprints in a lot of businesses can use the multiplicity of their products and services to create what they call moats around their businesses and to use the linkage between them to lock customers in,” he adds.

If the Justice Department moves ahead with its lawsuit and wins, which could take years, Kwoka says the end result would be undeniably positive for non-Apple customers and the tech market more broadly. Apple’s integrated ecosystem will still be there for those who enjoy it and want it. But for Android users, who are used to picking and choosing which hardware and software they want to use together, it would open up even more options. It’s something Apple is already exploring because of the European Commission’s Digital Markets Act, which aims to crack open entrenched tech ecosystems.

“In this case, it should be quite advantageous to consumers who want to make those choices,” Kwoka says. “It will bring prices down because there will be competition for parts of the package of services.”

“These are all hugely important cases in products and services that we’re using as we speak and we use every day,” he adds. “It will make a significant difference.”