Can space travel impact female fertility? Northeastern student takes part in NASA mission to find out

Dillon Nishigaya is doing research with NASA to determine the impact spaceflight has on the female reproductive system.

When he was in third grade, Dillon Nishigaya took a school field trip to NASA’s Ames Research Center in Mountain View, California, that would set the trajectory of his life.

Built in 1939, the center is located in the heart of Silicon Valley and is where NASA conducts some of its most innovative and groundbreaking research. The agency’s fastest supercomputers, the world’s largest motion-based flight simulator and the world’s largest wind tunnel are located there.

“I absolutely fell in love. I wanted to be an astronaut. I wanted anything and everything to do with space,” he says. “As time passed, it became a passion of mine. I got a bunch of books. I would read about Neil Armstrong, and I did all my presentations in science classes having to do with space.”

Little did he know that he would one day not only intern at the center, but play a role in helping the space agency understand the impact space travel has on female fertility.

The third-year biology and pre-med major at Northeastern University has been spending his winter break in Sarasota, Florida, working hand in hand with NASA’s Space Biology Biospecimen Sharing Program team.

The group recently sent some female rodents into space to see if it could track temporary or permanent alterations to the rodents’ reproductive capabilities as part of NASA’s Rodent Research-20 (RR-20) mission.

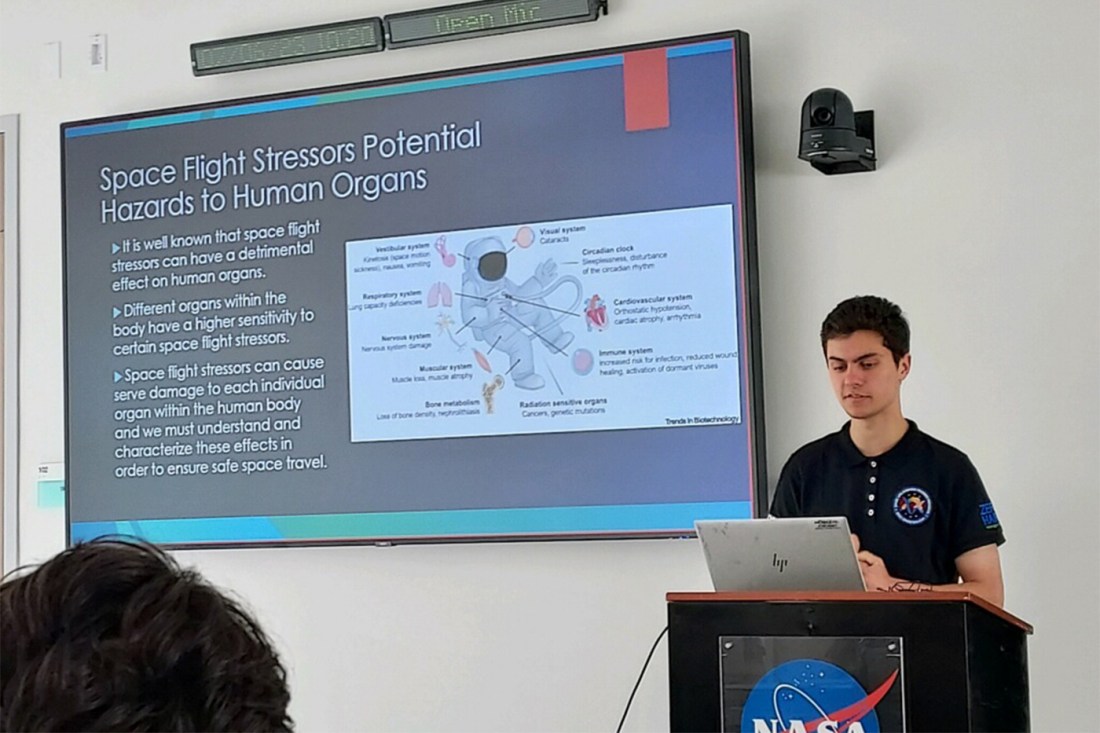

Nishigaya’s involvement builds off his co-op at NASA last summer, where he focused his research on “understanding the effects of space flight stressors on female fertility and ovarian function during deep space exploration,” he says.

Nishigaya continues on with that research in Northeastern’s Laboratory for Aging and Infertility in Boston as part of a collaboration he established between NASA and the university.

And he says participating in the RR-20 mission has helped inform his own research since there is still much to study and examine on the subject.

The rodents returned home on Dec. 22, and Nishigaya has spent the past week dissecting the specimens to help researchers study and analyze the rodents’ reproductive organs.

“It’s essentially the first step in the research process, and to be a part of this is fascinating,” he says.

There are a number of environmental factors in space that could potentially negatively affect a woman’s fertility, explains Lane Christenson, the principal investigator of the NASA RR-20 rodent mission.

Featured Posts

“Microgravity, radiation and spaceflight (launch and return) are the three main factors. All of these induce stress responses which can impact ovarian function,” he says. “Disruption of ovarian function will ultimately negatively impact fertility, but can also have impacts of the endocrine system (i.e., estrogen production) which in turn can impact a variety of physiologic systems, including cardiovascular, musculoskeletal and neurological systems in addition to the reproductive system.”

During his co-op, Nishigaya worked closely with Lauren Sanders, a staff scientist with the Blue Marble Space Institute who was contracted by NASA, to analyze some rodent ovaries that had been subjected to some “simulated space stressors.”

Those stressors included exposing the ovaries to increased levels of radiation and placing them in centrifuges with simulated microgravity.

“These are two of the most significant stressors that human astronauts experience when they go into space,” Sanders says. “These have a variety of health impacts that have been studied in different bodily systems, but their impact on female reproductive health is still being characterized.”

While working with Sanders, Nishigaya reached out to Christenson, given his understanding of the impact of female fertility in space, to help inform his work. From those conversations, Nishigaya was invited to take part in the RR-20 mission.

“He expressed interest in the project and followed through with completing the necessary training, his assistance has been very beneficial to the timely collection of samples over the last week,” Christenson says.

Nishigaya has been waking up at 3 a.m. with a crew of 15 and heading to NASA’s Sarasota facility to complete the examination of the rodents at 4 a.m. It has to be done at the time to account for the time difference on Earth between astronaut time in space, he says.

Nishigaya says he is looking forward to seeing the results of the space flight mission and how it compares to his own research, which relied on simulated experiments.

“The results will tell a lot about my findings, how accurate they are, and help us perform more experiments on Earth,” he says.