Mainstream environmental nonprofits get the most philanthropic support, at the expense of diverse organizations, research says

Environmental nonprofit organizations that have diverse leadership and work in equity-deserving communities receive considerably less philanthropic support than conventional, mainstream nonprofits, research finds.

That hurts everyone, says Jennie Stephens, dean’s professor of sustainability science and policy at Northeastern University and a 2023 Radcliffe-Salata climate justice fellow at Harvard Radcliffe Institute.

“It means that the ideas, solutions and proposed actions are oriented toward more mainstream communities,” Stephens says. “And it leads to reinforcing inequities among different households, communities and regions and perpetuates this landscape where ‘environmentalism is not for everyone.’”

Stephens, author of the book “Diversifying Power: Why We Need Antiracist, Feminist Leadership on Climate and Energy,” says governments around the world have not funded environmental action and decarbonization sufficiently.

That has led to increased dependency on philanthropy, or donations from wealthy individuals, trusts and organizations.

Unlike public funding, philanthropic resources are not allocated through democratic processes, Stephens says. Instead, they are often distributed because of connections, prior relationships and social networks.

It leads to reinforcing inequities among different households, communities and regions and perpetuates this landscape where ‘environmentalism is not for everyone.’

Jennie Stephens, dean’s professor of sustainability science & policy and director of strategic research collaborations at Global Resilience Institute

Stephens joined Christina Hoicka, Canada research chair in urban planning for climate change and associate professor at the University of Victoria, to look at environmental philanthropy for the low-carbon energy transition, using the example of Canada.

While Canada set an ambitious climate goal in 2005 of reducing greenhouse emissions by 40% to 45% by 2030, Stephens says, it has not managed to bend the curve on emissions and continues to invest in fossil fuels and approve new fossil fuel development projects.

Many studies have shown, she says, that more funds need to be invested in marginalized communities.

“So one might expect more of the funding going toward organizations that are focused on marginalized groups,” Stephens says. “But what we’ve found that is not the case yet.”

Their research demonstrates that environmental philanthropy in Canada favors a large set of established organizations. Organizations with diverse leadership from marginalized populations, which more often address issues in equity-deserving communities (that have identified barriers to equal access, opportunity and resources due to disadvantage and discrimination) are funded nearly three times less often.

Out of 462 nonprofit organizations that the researchers identified as working on a low-carbon energy transition, only 106 were led by people from equity-deserving communities such as Indigenous people, youth, low-income households, people of color and seniors.

Philanthropic organizations funded 60% of all the low-carbon energy nonprofits, while only 25% of diversity-led organizations received philanthropic funding.

Among the diversity-led organizations, about half of the Indigenous-led organizations received philanthropic funding, but many other minority-led organizations did not receive any.

Few conventionally-led organizations reported a commitment to gender diversity, low-income households, racialized communities inhabited by people from various racial and ethnic backgrounds, immigrants and refugees, northern and coastal communities of Canada, persons with disabilities or seniors.

“Reliance on philanthropy is not inclusive, it is not democratic, it doesn’t necessarily meet the public good or the needs of communities, and it can actually take away resources from the people who need them the most,” Stephens says.

“It ends up reinforcing these patterns that the research has shown are really unhelpful in terms of making society-wide change, because it prioritizes some people and excludes and disempowers others.”

For example, historically, a lot of environmental projects have focused on conservation and creating green spaces, Stephens says, and not as much on mitigating health-related consequences of climate change and environment pollution.

“Some of my team’s previous research demonstrates that when we don’t have diversity when thinking about energy and environmental issues, we tend to dismiss and disregard a lot of the health and economic injustices of our current systems,” Stephens says.

Stephens believes environmental inequity is a big problem because the scale of change needed to address climate change and move toward a fossil-fuel-free future is colossal and requires everyone’s needs to be considered.

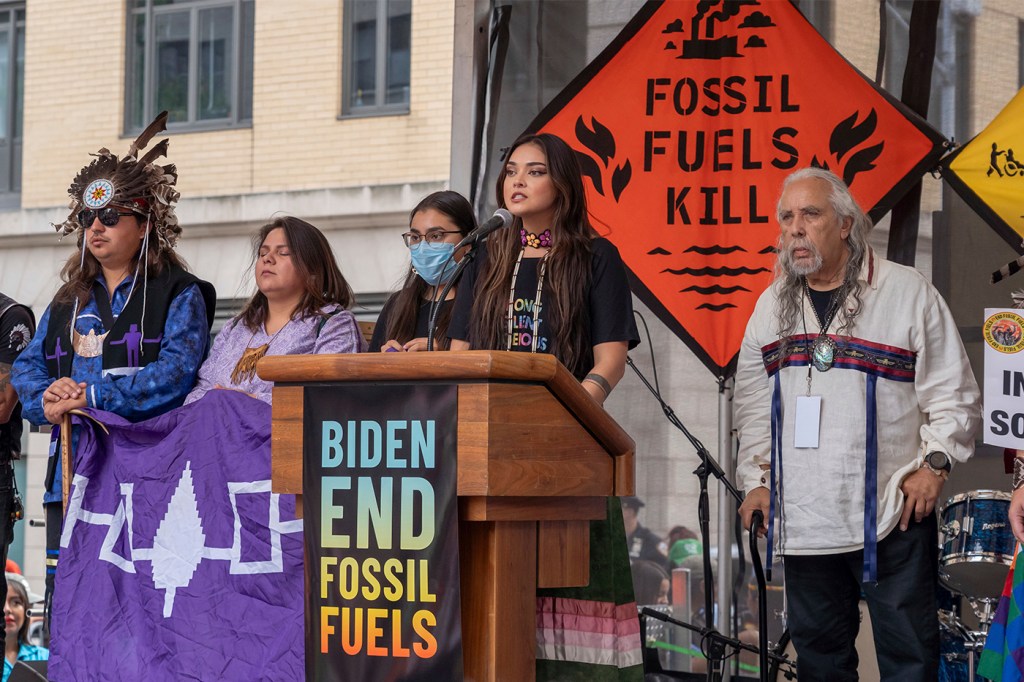

Diverse leadership is crucial, Stephens says, because women, Indigenous people and people of color have different lived experiences and bring different perspectives, priorities and principles to the leadership of organizations.

“When we support the same organizations that have been trying the same things over and over, we actually can’t expect transformative change,” she says. “We need new ideas, we need to expand the leadership base and who’s getting funded.”

Alëna Kuzub is a Northeastern Global News reporter. Email her at a.kuzub@northeastern.edu. Follow her on X/Twitter @AlenaKuzub.