Will dreaded yellow fever return to the southern US?

It’s been more than 100 years since the mosquito-borne yellow fever virus killed tens of thousands of people in epidemics that raged across the American South and into Texas.

Now scientists writing in the Oct. 19 edition of the New England Journal of Medicine warn that yellow fever could reemerge in Southern states, thanks to climate change creating suitable environments for disease-carrying Aedes aegypti mosquitoes.

There is still time to prepare for possible yellow fever outbreaks, but the U.S. needs to take action as soon as possible to prevent them, say Richard Wamai, Northeastern professor of cultures, societies and global studies, and Neil Maniar, director of Northeastern’s Master of Public Health program.

“It is inevitable that yellow fever and other vector-borne diseases will continue their march here in this country, including the march from the South to the North as temperatures shift upward,” Wamai says.

“That will happen without a question. The issue is, can we implement better controls?”

Combating yellow fever will take a combined approach, including vaccination, surveillance and control of mosquito populations, known as vector control, Wamai says.

“We shouldn’t assume that just because we haven’t had an outbreak in over 100 years of a certain illness that we may not have additional outbreaks in the future, because climate change is proving otherwise now,” Maniar says.

“Warmer months are lasting longer. We have increasing amounts of rainfall, higher levels of humidity,” Maniar says. “We’re going to see a longer stretch of the year where we have those favorable conditions for mosquito-borne illness.”

Why scientists are concerned

The New England Journal of Medicine report says mosquito-borne infections have “begun accelerating in the American South,” with Florida and Texas experiencing outbreaks of dengue, chikungunya and Zika virus infections within the past decade.

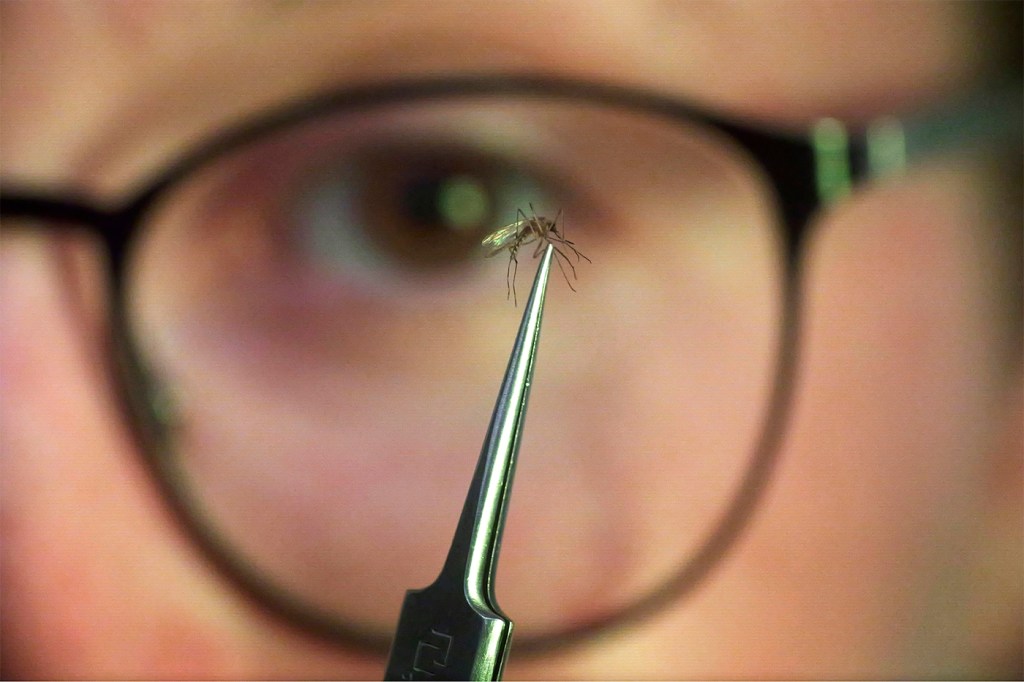

All these diseases are carried by the same aedes mosquito that also transmits yellow fever, part of the reason researchers in the New England Journal of Medicine say “there are new reasons to be concerned about a potential reemergence.”

Yellow fever has a deadly legacy in the U.S., being responsible in the 1800s for the deaths of tens of thousands of people in southern U.S. coastal cities and cities on the Mississippi River.

“An 1853 epidemic in New Orleans may have killed 11,000 people or almost 10% of the population. And over a five-month period in 1878, Mississippi Valley cities, especially Memphis and Vicksburg, saw an estimated 120,000 people become ill and 20,000 die,” the article says.

Even Northern cities have been afflicted. The American Society for Microbiology says a record heat wave in Philadelphia in 1793 caused a yellow fever outbreak that decimated the population in a matter of months.

More recently, yellow fever reemerged in Venezuela in 2019, and Brazil “experienced an epidemic nearly three times the size of any recorded in the previous 36 years” from 2016-2019, according to the New England Journal of Medicine article, which blames a warming climate that promotes diseases carried by the Aedes aegypti mosquito.

“I would be as concerned about yellow fever as I would about some other mosquito-borne illnesses in terms of the risk for an increase in the number of cases here in the U.S. or the increase in the risk for potential outbreaks in certain areas of the country,” Maniar says.

What is yellow fever

Yellow fever came to the Western Hemisphere from Africa during the forced transport of enslaved people, Wamai says. The World Health Organization says that as of this year, the disease is endemic to areas of 34 African countries and 13 countries in Central and South America.

There is no human-to-human transmission of the disease, which is caused by the bite of an infected female mosquito, Wamai says. But outbreaks often occur in heavily populated areas to which the mosquitoes are drawn.

The Centers for Disease Control says symptoms may come on quickly and include chills, fever, severe headache, back pain, body aches, nausea, fatigue and weakness.

Most people recover but the mortality rate for those with severe illness can run as high as 60%, Wamai says. “People vomit, hemorrhage. Kidney function deteriorates.”

The “yellow” refers to the jaundice that afflicts some people with the disease, Wamai says.

He says the most recent global estimate of yellow fever burden reports that in 2018 there were 109,000 critical infections and 51,000 deaths in Africa and South America, a 46.8% fatality rate.

There’s no targeted treatment but there is a vaccine

“There are no treatments for yellow fever,” Wamai says. Patients receive supportive care to manage their symptoms, including rest, fluids and the use of pain and fever-reducing medications.

“The solution is a vaccine,” which has proven very effective and only gotten better over time, Wamai says.

“Once someone has a vaccine, they have lifetime protection,” Wamai says.

The other benefit of being vaccinated is that the immunized person is no longer a potential competent carrier of yellow fever and cannot transmit the virus to biting mosquitoes, he says.

Whether the U.S. has enough yellow fever vaccine to immunize people in the event of an outbreak is questionable, Wamai says.

One solution could be to offer a “fractional vaccine,” such as a fifth of a regular dose, which might only last one year, he says.

That could buy enough time to vaccinate many more people than the number of full doses available in order to get through an outbreak while vaccine production is ramped up, Wamai says.

He says Northeastern students who have traveled to Kenya to work in his clinic for the treatment of visceral leishmaniasis have received fractional doses of yellow fever vaccine when Boston hospital travel clinics ran low.

“The bigger issue is: what if? What if there’s an outbreak of yellow fever here in the U.S.? What if we start to see more cases, then what?” Maniar asks.

“Are we prepared for that? And in areas of the world where yellow fever is endemic, (can we) make sure there is enough of a supply of vaccine to control yellow fever in those areas?” Maniar says.

Yellow fever ‘not eradicable’

Higher temperatures, rainfall and humidity help mosquitoes thrive, and so does poverty, Wamai says.

People housed in areas with bad sanitation and drainage and in homes with ill-fitting screen doors and windows are living in conditions ripe for mosquito-borne illnesses to emerge, he says.

There is a need for consistent surveillance of mosquito populations, as well as for measures to control their growth, Wamai says. The CDC says mosquito control measures include eliminating mosquito larval habitats and applying larvicides to kill mosquito larvae.

Non-human primates are reservoirs for yellow fever “so there is no way to eradicate it,” says Wamai. “You can’t kill off all the animals.”

“The way to ensure it doesn’t come back is by maintaining surveillance, maintaining vector control and ensuring readiness for vaccination and large campaigns to vaccinate people,” he says.

Cynthia McCormick Hibbert is a Northeastern Global News reporter. Email her at c.hibbert@northeastern.edu or contact her on X/Twitter @HibbertCynthia.