Does banning books really help kids? A childhood education expert weighs in

When Jaci Urbani taught early learners at the Pennsylvania School for the Deaf, one of the books she read to them was “Charlotte’s Web,” by E.B. White, a children’s novel about a pig destined for slaughter and his friendship with the barn spider who saves him.

While Wilbur is saved (spoiler alert), by the end of the book, Charlotte dies. It was at this point some of the children would start to cry.

Here is where some educators and parents would put the book away and not take it out again. Instead, Urbani approached the moment with empathy and used it to open up a discussion with students about whether they’ve experienced loss and how they take care of themselves and others when they’re sad.

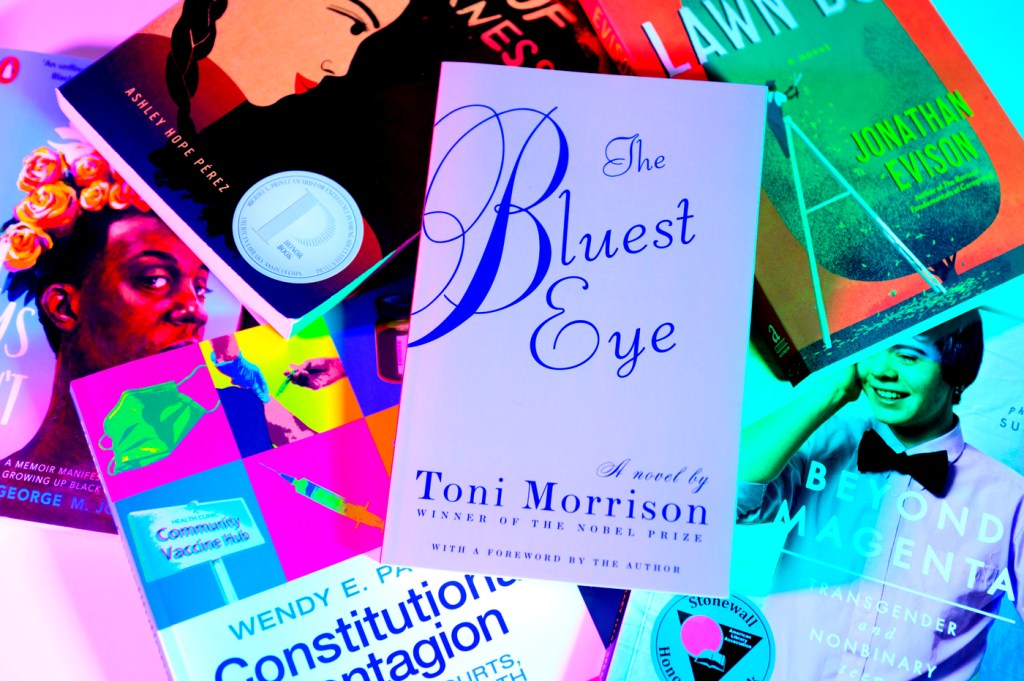

Others prefer to keep books addressing issues they find difficult out of kids’ hands, an approach that is becoming more and more common in the form of book challenges and bans in schools across the country. Many of the most frequently challenged books are being targeted for containing LGBTQIA+ and sexually explicit content, including having depictions of sexual abuse, topics some say parents should be the ones introducing to children.

But Urbani, now a professor of education at Northeastern University in Oakland and a childhood education expert, said we should be talking to children about uncomfortable topics and books allow for those conversations.

“Just because death is a sad topic doesn’t mean we shouldn’t talk about it with kids and help them,” she added. “Those are the kind of conversations that we should have around these topics we find difficult. … There’s so many things that people can learn about and if it’s handled in a mature, developmentally appropriate way, kids can learn from it.”

The American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom documented 1,269 demands to censor library books and resources in 2022 with 2,571 unique titles targeted by censors. This is nearly double the 729 attempts documented in 2021 and doesn’t account for attempts not reported or covered by the news. It’s also the highest number the ALA has seen since it began tracking book challenges over two decades ago.

The ALA found nearly half of demands were made by parents, patrons or political/religious groups. The vast majority were targeting not just one single book, but multiple titles. At least 40% of challenges targeted more than 100 books at once. In Texas, for example, there were 93 challenges to 2,349 titles.

The most challenged books of 2022 range from graphic memoirs (“Gender Queer: A Memoir” by Maia Kobabe was number one on the list) to classic literature (Toni Morrison’s “The Bluest Eye”) to popular fantasy novels (“A Court of Mist and Fury” by Sarah J. Maas). While the books may range in genre and topic, what many of them have in common is the reasons for being challenged.

“These numbers and the list of the Top 13 Most Challenged Books of 2022 are evidence of a growing, well-organized, conservative political movement, the goals of which include removing books about race, history, gender identity, sexuality, and reproductive health from America’s public and school libraries that do not meet their approval,” the ALA wrote in its 2022 book censorship data snapshot.

Some of the organizations behind these bans, like Moms for Liberty, argue they are standing up for the rights of parents and they themselves want to be having these conversations with their kids. But are these bans helping or hurting kids?

There’s so many things that people can learn about and if it’s handled in a mature, developmentally appropriate way, kids can learn from it.

Jaci Urbani, a professor of education at Northeastern’s Oakland campus

Urbani takes the stance that they do more harm than good. Instead, books addressing so-called difficult topics can open avenues for discussions between kids and the adults in their lives (topics, she adds, they are probably already exposed to through friends and other media).

“Our society doesn’t like to talk about bad things,” she said. “It’s just shut down. It’s not engaging in a conversation around it. But kids know things. They’re very perceptive. I think it’s much more harmful that they have these book bans in place because kids need this knowledge and quite frankly, the adults who are banning these books need that knowledge.”

Additionally important for parents concerned about their kids’ reading material is looking at content in context. Art Spiegelman’s graphic novel “Maus,” which depicts his father’s experiences in the Holocaust, has been challenged for its language and for having an image of a partially naked woman. But in the context of the book, Urbani said, it’s appropriate.

“There’s nothing sexy about it,” she added.

But what if a child reads a book beyond their maturity level? Is that harmful? Urbani says there is a conversation to be had about whether some books are appropriate for a child’s developmental capability. For example, you wouldn’t read John Steinbeck’s “Of Mice and Men” to a kindergarten class or dive into the brutality of slavery with a group of preschoolers.

“What we should all be engaging in a conversation together,” Urbani said. “There’s a responsibility to talk about things that are real in the world without getting into explicit detail.”

Urbani says each child will be different and she encourages parents to consider their child’s maturity level and be open to having conversations if their child reads something that confuses them or is beyond their maturity level. For educators, Urbani says looping in parents and letting them read their children’s assigned reading and encouraging them to talk about it with their students can be helpful, as can bringing in additional support in the form of a school counselor.

But what you can do instead is introduce difficult topics in an age appropriate way.

“(Enslaved people) were kidnapped from their families and their countries and their potential futures, and were forced to work to make money for somebody else in horrible conditions,” Urbani said. “I’m not going to say that to a 5-year-old. But I will talk about how we treat each other and how we want to care for each other in our classroom. That’s how you relate it. … I’m not going to talk about rape and beatings, but I will talk about the absolute right and wrong of slavery. Trying to whitewash it is just a way to lie to children because it makes adults uncomfortable.”

Erin Kayata is a Northeastern Global News reporter. Email her at e.kayata@northeastern.edu. Follow her on Twitter @erin_kayata.