How are people with aphasia actually using language? Award-winning researcher moving from the lab to the real world

People who have a stroke or traumatic brain injury sometimes experience aphasia, a disorder that affects a person’s ability to express or understand language.

Research by Northeastern University assistant professor Erin Meier aims to better comprehend how people with aphasia use language in their daily lives.

“I’m really interested in how people with aphasia are actually using language in the real world, and how their recovery affects their ability to communicate in real world environments,” says Meier, who is director of the Aphasia Network Lab at Northeastern.

Meier has received a prestigious national research award in recognition of her work in language and cognitive recovery after stroke.

Meier, an assistant professor of communication sciences and disorders at the Bouve College of Health Sciences, received an Early Career Contributions in Research Award from the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association—a national professional, scientific and credentialing association.

The award honors researchers who are within five years of receiving their terminal degree or completing postdoctoral work. Meier will accept the award at the association’s annual meeting, which is held in Boston this year.

Meier’s research stems from her time as a speech pathologist at an outpatient day therapy program where she focused on stroke survivors, traumatic brain injury survivors as well as people with neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s disease and multiple sclerosis, many of whom had aphasia. Aphasia is a disorder that affects a person’s ability to express and understand written and verbal language and often occurs after a stroke or brain injury.

Meier explains that typical aphasia research is done in a lab with tests—often written—asking patients to identify pictures of objects. But people with aphasia often experience what Meier describes as “extreme tip-of-the-tongue,” where they understand what an object is, recognize it, but just can’t think of the name of it.

Moreover, Meier says there is “just so much variability in how people respond to therapy,” particularly depending on the setting.

“Some (of the patients in the day therapy) would do great in the clinic, and then completely break down in a real-world setting,” Meier says.

So, Meier is embarking on three research projects that moves aphasia research from the lab to the real world.

She and professor Stephen Intille of the Khoury College of Computer Sciences are conducting a study where participants are asked to identify objects that appear on smart watches the people with aphasia wear as they go about their daily lives, doing laundry, going grocery shopping, etc.

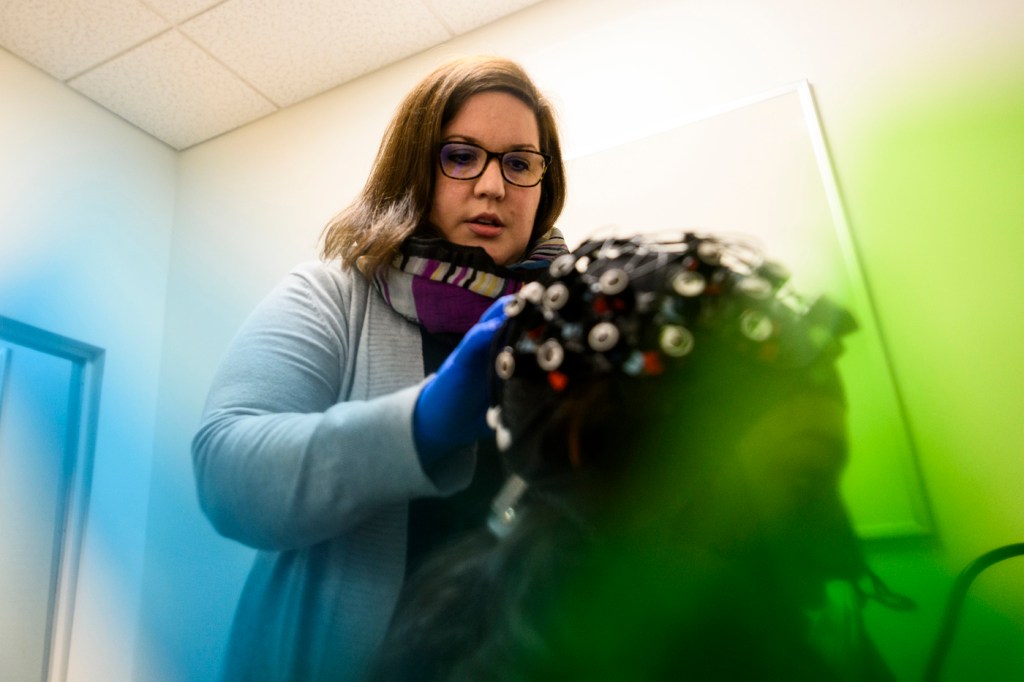

Meier is also working on a study that analyzes brain activity of people in the early stages of aphasia. Again, the setting is non-clinical; the brain imaging method—called functional near-infrared spectroscopy—is portable and wearable, so that it can be used in the patients’ home.

“It fits into the broader scope of research of trying to understand brain research in more naturalistic settings,” Meier says.

Finally, Meier and Josh Stefanik of Bouve and Qianqian Fang of the College of Engineering are using the same technology to analyze brain activity in younger and older healthy adults who are using a treadmill and communicating—basically examining what happens to people when they “walk and talk” at the same time.

“Erin is the quintessential rock star assistant professor that every department wants,” Emily Zimmerman, associate professor and chair of the Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders, says. Zimmerman nominated Meier for the award.

“Her research is so impactful that grant funders and community members all want to be involved, and I think that really speaks to the importance of Erin’s work,” Zimmerman continues. “I think Erin really embodies the outside-the-box thinking that is aligned with Northeastern’s vision.”

Cyrus Moulton is a Northeastern Global News reporter. Email him at c.moulton@northeastern.edu. Follow him on Twitter @MoultonCyrus.