World’s largest undersea science station will provide one-of-a-kind co-op experience

Imagine a co-op experience in which Northeastern University students live for weeks at a time in the world’s largest undersea science station, venturing into the surrounding Caribbean waters on daily scuba dives.

This type of experiential learning is one step closer to reality thanks to an agreement between Northeastern and the developer of the underwater station, Proteus Ocean Group.

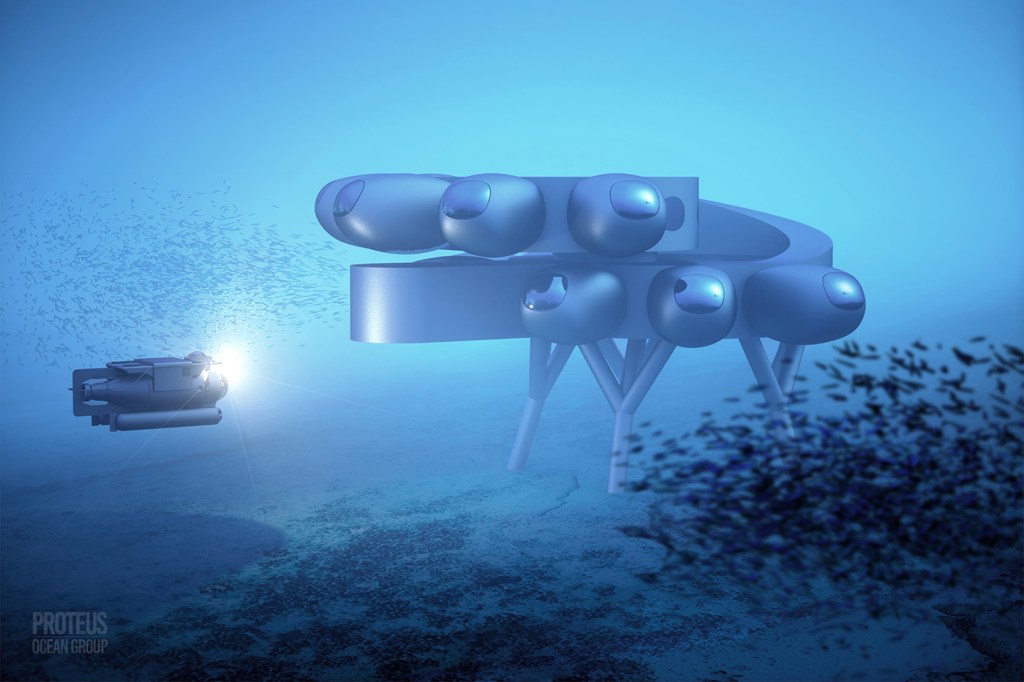

Founded by Fabien Cousteau, grandson of famed ocean explorer Jacques Cousteau, Proteus plans to have a modular underwater habitat observatory and lab installed off the coast of Curacao, possibly by the end of 2025.

Marine scientists Brian Helmuth and Mark Patterson are Northeastern’s chief science advisors for the Proteus project. Both work at the Coastal Sustainability Institute of the Marine Science Center in Nahant, Massachusetts.

“This formalizes Northeastern as the go-to institution,” Helmuth says.

“Because of the tremendous research and educational value that this habitat will provide, our ambitions on the Northeastern side are really to involve students at all levels,” says Patterson, who directs the field robotics laboratory at Northeastern.

It won’t be just the students in marine science going to Curacao, Patterson says.

“It will be engineers and health sciences students,” he says, “because so much of what Proteus will enable will be not just marine science, but training for going into outer space and the effects or isolation and extreme environments on humans working together.”

“It really could be a university wide game changer once it’s up and running,” he says.

Patterson and Helmuth joined Cousteau at potential underwater station sites in Curacao at the end of April, completing nine dives at eight sites. Curacao was picked as a location because it is out of the path of seasonal hurricanes and has the support of the island government.

The requirements for the final site require that it be ecologically interesting, not harm coral reefs in its construction, be safe for divers and allow construction at the right depth, Helmuth says.

Cousteau’s vision is to house 24 aquanauts at a time at a depth of up to 60 feet. Anything deeper would require the use of a specialized mixed gas instead of standard air for breathing, Helmuth says.

Unlike a sealed pressurized system such as a submarine, the pressure inside and outside the underwater station will be equal—which means the aquanauts can scuba dive outside for eight or more hours a day without having to take a break to decompress.

Normally scuba divers descending as far down as 60 feet have to resurface within 56 minutes before they risk a life-threatening situation known as the bends.

Living in a Proteus module underwater means scuba divers can wait to pack all their decompression into a 24-hour period at the end of their stay, says Helmuth, who calls it “the gift of time.”

Proteus Ocean Group also has signed memorandums of understanding with the government of Curacao and NOAA, the latter of which signals the federal agency’s interest in returning to undersea exploration and a source of possible future funds for the underwater station, Helmuth and Patterson say.

“It’s rare for NOAA to engage at this level with the university and with Proteus Ocean Group,” Patterson says.

“They view Proteus as the International Space Station of the sea floor,” Helmuth says.

Patterson says, “It’s all about the new emphasis on public/private partnerships with the U.S. government, which is a big initiative as well of the National Science Foundation.”

The Proteus Ocean Group also anticipates developing partnerships with NASA and using the underwater station as a training site for astronauts from NASA and private industry.

“It’s the closest analogue to being in outer space in terms of living in a confined location. You are living in a different world, and you can’t just hop up to the surface to return home,” Helmuth says.

“Having neutral buoyancy in the water outside lets you simulate spacewalks,” he says.

Patterson says NASA is already using the world’s only existing underwater science station, the Aquarius Research Station in the Florida Keys, for once a year astronaut training.

The exact size of Proteus has not been established yet, but it could be as large as 2,500 square feet—far larger than the 400-square-foot, 37-year-old Aquarius station run by Florida International University, Patterson says.

There will also be plenty of land-based student research opportunities associated with the Proteus Ocean Group, the scientists say.

Northeastern Ph.D. student Angela Jones, who is working on carbon sequestering, and master’s degree student Reena John, who has an interest in ocean acidification, are already listed as interns on the Proteus Ocean Group’s website.

In addition, two other Northeastern students have worked on underwater station-related topics of sustainable aquaculture and using marine organisms to make anti-cancer drugs and antibiotics.

“The sea, in particular coral reefs, are probably going to be our best hope for finding new things,” Patterson says.

Cynthia McCormick Hibbert is a Northeastern Global News reporter. Email her at c.hibbert@northeastern.edu or contact her on Twitter @HibbertCynthia.