Scientists discovered the largest ever cosmic explosion. What’s the big deal about this big bang?

Astronomers have discovered the biggest cosmic explosion ever witnessed, a massive burst of energy 2 trillion times brighter than our sun and 10 times more powerful than the most powerful supernova.

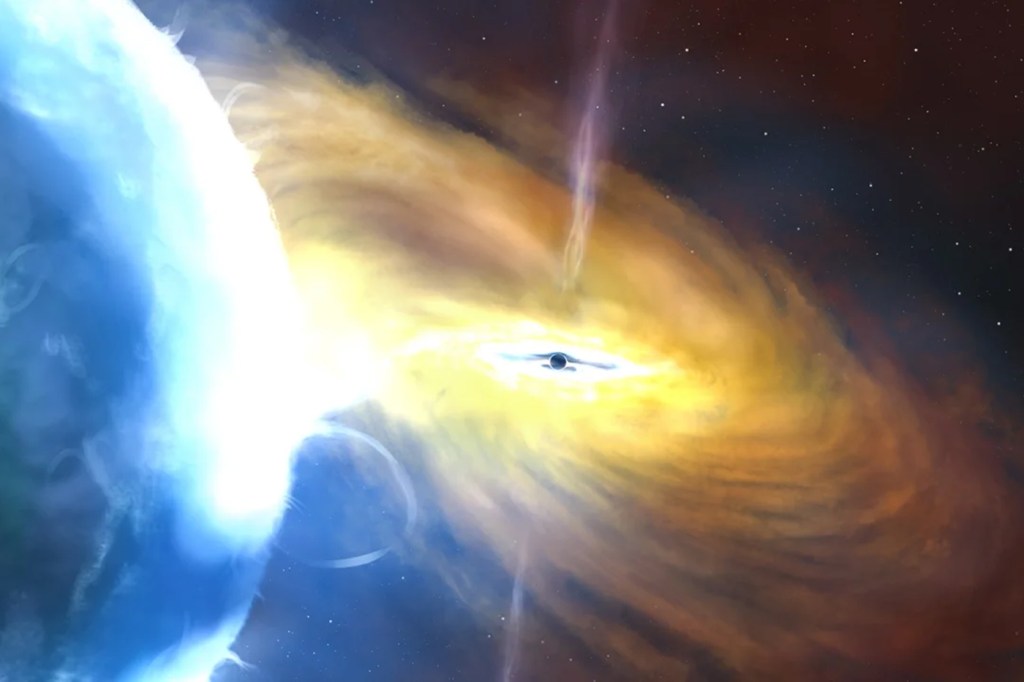

The explosion, which occurred 8 billion light years away from Earth billions of years ago, has been erupting for three years without any signs of slowing down. Although scientists at first struggled to determine the cause of the cosmic blast, which they have named AT2021lwx, they now think the culprit is a supermassive black hole that came in contact with a gargantuan cloud of gas. That’s according to findings recently published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Stretching across a space that is 100 times the size of our solar system, the black hole formation is currently giving off 100 times more energy than the sun will emit over the course of its entire 10-billion-year lifetime.

The explosion itself is far from Earth, but its discovery could help scientists better understand black holes, which sit at the center of many galaxies, including our own.

“It really seems like, especially when they have time to do some more modeling, this will be an important step in understanding what’s happening in the middle of galaxies,” says Jonathan Blazek, a physics professor at Northeastern University.

Astronomers at the Zwicky Transient Facility in California originally discovered AT2021lwx in 2020 but struggled to suss out the exact cause of such a massive explosion. AT2021lwx was emitting too much light for too long to fit any known category of astronomical phenomenon, whether it was a supernova, aka an exploding star, or a tidal disruption, which occurs when a star has been pulled into a black hole and destroyed.

Eventually, NASA’s Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory, Chile’s New Technology Telescope and Spain’s Gran Telescopio Canarias were all brought online to aid in studying AT2021lwx. With all these telescopes pointed at AT2021lwx, astronomers eventually identified the black hole-related explanation they have settled on in their findings.

Blazek says the astrophysical qualities of a black hole definitely are primed to cause an explosion at this scale. Once a black hole gets large enough, it creates such a gravitational whirlpool that it starts sucking in anything that’s close to it, growing in the process. Anything that crosses the event horizon, the point of no return, and falls into the black hole is gone––it will never be seen or heard from again. That includes light.

So, how does a black hole cause an explosion with enough light to be seen billions of light years away by scientists on Earth?

“Because these are such big, extreme objects, you can have some pretty big, extreme things happening just outside the event horizon,” Blazek says.

The pull of a black hole is so strong that anything caught in its wake gets accelerated to the point where it’s moving near the speed of light, creating swirling, rapidly moving particles that are bumping into each other.

“You get really, really, really hot material outside the event horizon of the blackhole, and this really hot material can emit a lot of energy,” Blazek says. “It turns out the most efficient way to get energy out of mass is to drop it into a black hole.”

According to Blazek, there is a whole class of active galactic nuclei (AGNs) that are powered this way. Mass falls into a black hole, it gets shredded at high velocities and emits a ton of energy. But typically those kinds of events create a steadily increasing amount of energy and light that scientists can observe. That wasn’t the case here.

“They can find no evidence that this was active before, so their best theory is that this was a blackhole about a billion solar masses [large] that was just sitting there quietly because nothing was around to fall in,” he says. “Then, they think a big mass of gas got too close and pretty quickly got shredded and fell in.”

Blazek says this explosion has similarities to other cosmic phenomena, like AGNs, but it’s the differences that make the discovery so exciting.

Blazek says understanding more about the nature of black holes could help with his own work, which involves using galaxies and the movement of mass through the universe to map the cosmos. Black holes are instrumental in moving all kinds of matter through outer space. Although astronomers have learned a lot about black holes, there is still much that isn’t known about how supermassive black holes are created. By further studying an event like this cosmic explosion, scientists could unlock even more about these powerful cosmic forces and the nature of our galaxy as well.

“We don’t fully understand how these things grow, especially early on in their lives,” Blazek says. “If we see an event where a cloud of more than 1,000 solar masses is falling onto a black hole, in the sort of event we didn’t know could happen, that could be an important piece of this puzzle.”

Cody Mello-Klein is a Northeastern Global News reporter. Email him at c.mello-klein@northeastern.edu. Follow him on Twitter @Proelectioneer.