New Ruggles Station exhibit features work of pioneering Black architects who helped shape Northeastern’s footprint

Thousands of commuters visit the Ruggles train station every day without realizing how the transportation hub, designed by pioneering Black architects, united Boston’s neighborhoods and helped Northeastern University grow into its current footprint.

A new public exhibit at Northeastern’s School of Architecture in Ryder Hall explains all that and more, says Amanda Reeser Lawrence, an architectural historian and associate professor in the College of Arts, Media and Design.

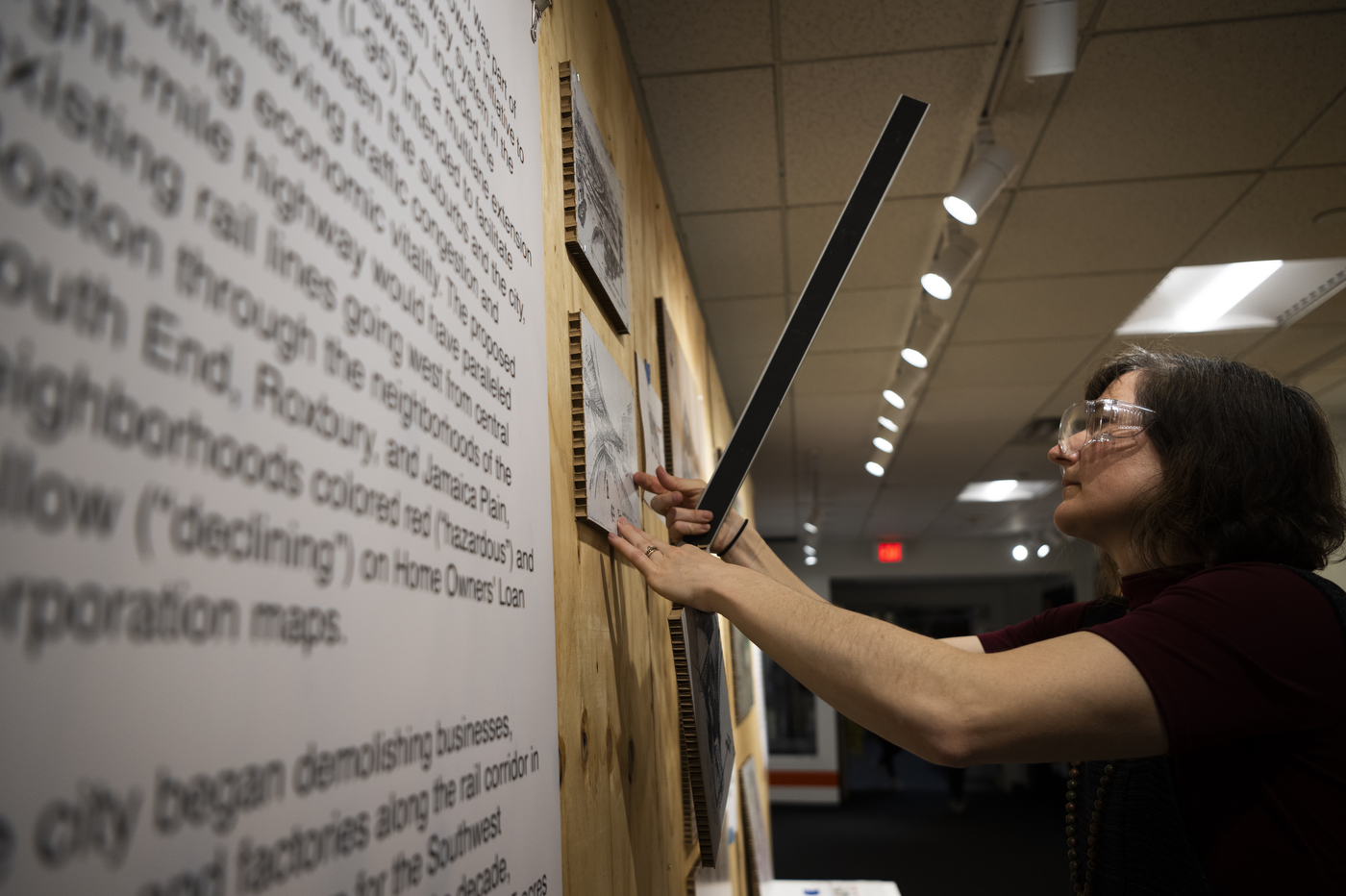

The hope is that “Ruggles In Dialogue” inspires the next generations of architects to see how community activism can literally transform neighborhoods. The exhibit opened Friday, April 7, and runs through the fall.

“In this exhibition you learn about how the design of the Ruggles station was shaped by anti-highway activism, community participation, government and redlining,” Lawrence says.

“The station is a conversation starter to talk about a lot of things,” says Mary Hale, an associate teaching professor in the School of Architecture and lead exhibit curator with Lawrence and associate professor Lucy M. Maulsby.

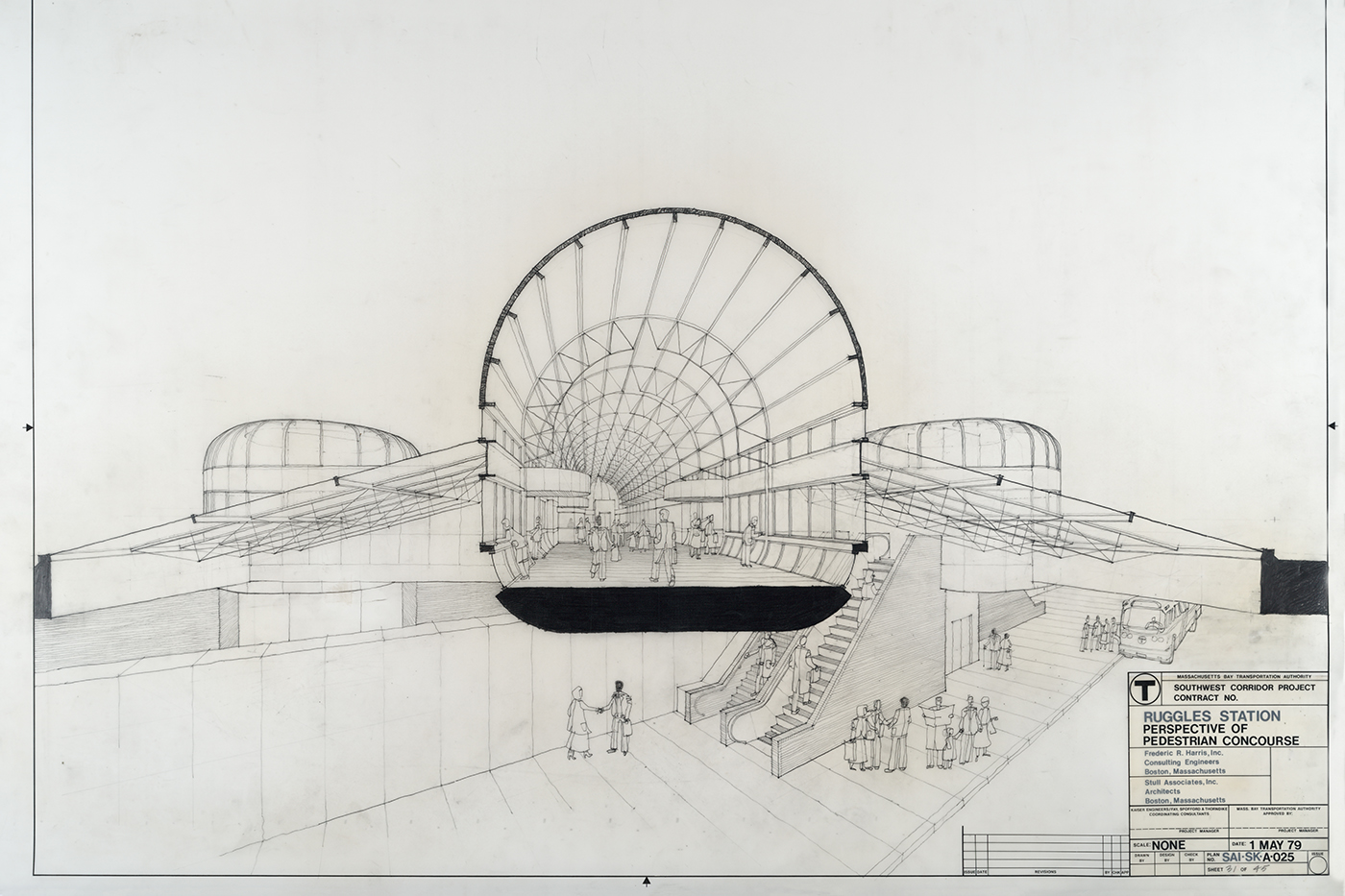

The exhibit features reproductions of architectural drawings by architects M. David Lee and the late Donald L. Stull, whose original papers are held by Northeastern’s Archives and Special Collections.

Because the exhibit is in a public gallery space at Ryder Hall, the curators decided to use reproductions rather than the actual archival materials of the pioneering Black architects.

The architectural firm, Stull and Lee, designed not only the Ruggles station, but also Northeastern’s John D. O’Bryant African American Institute, Roxbury Community College and the Boston police headquarters at Roxbury Crossing.

They were also lead architects for the Southwest Corridor Park that abuts Northeastern’s campus.

“They have projects all over the city,” Hale says.

She says when Stull, who died in 2020, founded the firm in 1966, it was a time when “there were only a handful of Black-owned architecture firms in the country.”

“They were very concerned with elevating minorities and women in their practice, which was unique among architecture firms at the time,” Hale says.

Right: Northeastern professor Mary Hale hangs a piece in Ryder Hall for the exhibit. Photo by Alyssa Stone/Northeastern University Bottom: Northeastern students check out the architecture exhibit in Ryder Hall on Ruggles Station and the role of Lee and Stull in unifying area neighborhoods and shaping the footprint of Northeastern. Photo by Alyssa Stone/Northeastern University

The vaulted concourse of the Ruggles Station, inspired in part by grand European rail stations of the 19th century, serves commuters passing through the elevated station that links Roxbury with Northeastern, as well as downtown, Huntington Avenue and the Fenway, Lawrence says.

When it opened in 1987, Ruggles aimed to unite neighborhoods that had been separated by embankments and rail lines.

“It’s a bridge in both directions across an embankment that had historically divided communities,” Maulsby says.

With Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority subways, commuter rail and buses using Ruggles Station, it is more than a bridge—it is a connection to Boston and beyond, she says.

“It’s about who has claims to the city, who is participating in the life of the city,” Maulsby says.

Ruggles Station was the fruition of an anti-highway movement that directed resources originally intended for the construction of a 12-lane highway to mass transit, community development and a public park, the professors say.

Stull and Lee used the momentum created by the anti-highway movement to engage neighborhood members and community activists in generating a vision for Ruggles Station, they say.

“Stull and Lee helped to realize a project that had many, many voices,” Maulsby says.

“They were part of a process that was really decades in the making” that included Gov. Francis W. Sargent’s 1970 moratorium on highway construction within Route 128.

“Stull and Lee really built on that work, harnessed the ideas that came out of the process and drew together a wide range of professionals, not just architects and engineers, but also landscape architects and graphic designers to really think about this project as a coordinated system,” Maulsby says.

One of the results was the creation of the Southwest Corridor Park that stretches 4.1 miles alongside the Orange Line route from Back Bay to Forest Hills.

The linear park was created out of land already cleared for the failed highway project and includes green spaces, garden plots, tennis courts, and walking and bicycle paths among city spaces.

Maulsby called it a contemporary response to Frederick Law Olmsted’s Emerald Necklace.

“It truly was a community process where they gathered feedback from community members and folded it into the design of the park,” Hale says.

“It wasn’t like the original highway plan, which was very top down, imposing something on the community.”

The Ruggles exhibit features not only architectural drawings but also documentary footage, aerial photos of the Northeastern campus and pamphlets from and photos of community meetings and anti-highway protests, Lawrence says.

“We have a fun interactive piece at the end” that asks people what they think of Ruggles Station and how they interact with the Southwest Corridor Park, she says.

Hale calls Ruggles “the physical embodiment of an absolutely incredible story.”

“It’s not a campus building, but we use it a lot,” she says.

Cynthia McCormick Hibbert is a Northeastern Global News reporter. Email her at c.hibbert@northeastern.edu or contact her on Twitter @HibbertCynthia