‘The DeafBlind community is an underserved community.’ Northeastern engineering students are designing more accessible doorbells

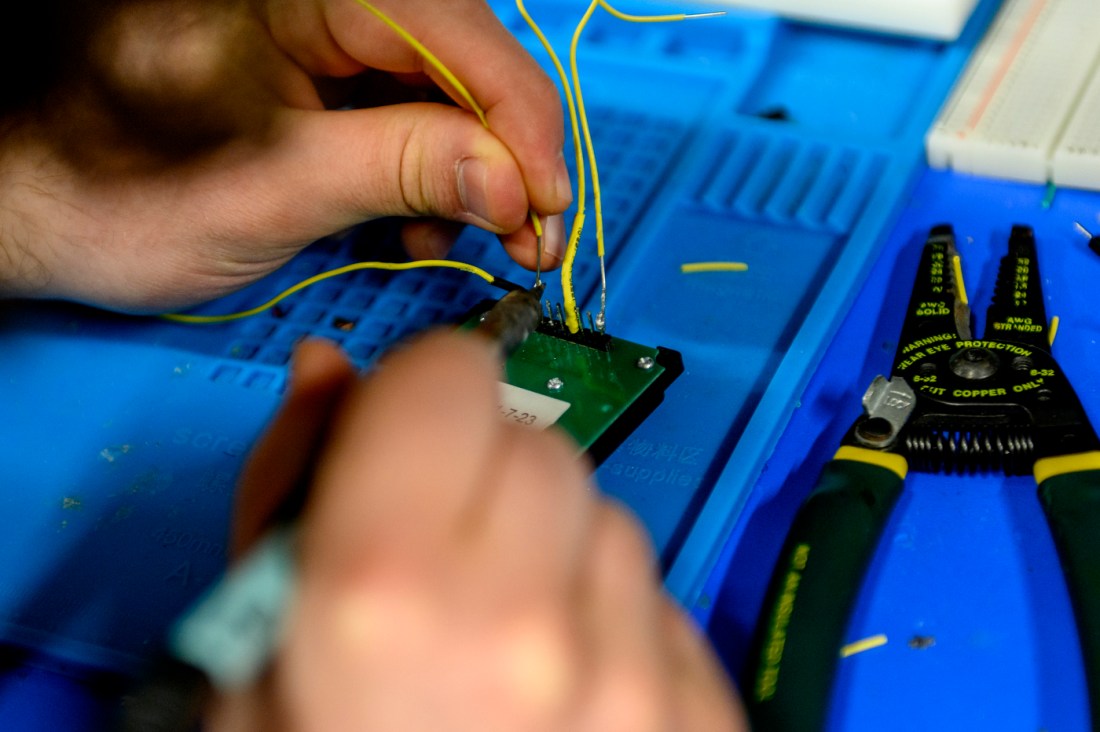

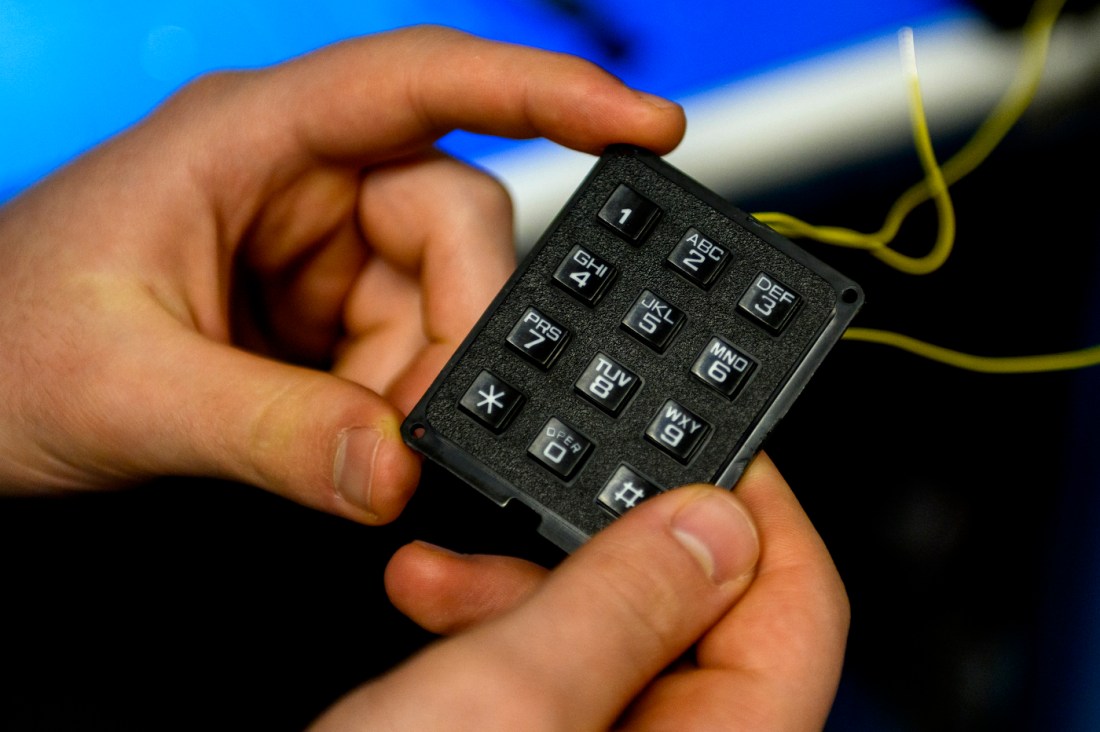

Hunched over a soldering table with safety glasses and deep intent on his face, Nick Scaperdas, a third-year bioengineering student at Northeastern University, focuses on the task at hand. Electrical wires stick out of an electric keypad in front of him, like the grasping tentacles of an octopus, as he connects yellow wires to what will eventually be a functioning doorbell.

But this isn’t an ordinary doorbell. Paired via Bluetooth with a bracelet, this doorbell literally helps open the door for people with concurrent hearing and vision loss, known as deafblindness.

“The way it’s going to work is we’re going to use Bluetooth to send a signal from the doorbell to the bracelet,” Scaperdas says. “The bracelet will receive the signal, and there’s a motor inside it that will vibrate and tell the person that someone’s there.”

It’s an ambitious project, but Scaperdas is not alone. He’s one member of a nine-student team that’s working as part of Generate, a student-led product development studio in Northeastern’s Sherman Center. Every semester, Generate engineers and designers form into teams and work with industry clients to design and develop products with real-world impact, all within a six-month semester.

In this case, Samantha Johnson, a Northeastern graduate and founder of Tatum Robotics, came to Generate with an idea. When DeafBlind people have helpers or family that need to get into their house, more often than not the solution is to leave the door unlocked, says Matias Dermond, a fourth-year mechanical engineering student and project lead. That presents some clear safety concerns.

In December, Johnson came to Dermond with the basic idea for the project––a wearable device with a motor that would connect via WiFi to a remote doorbell––but wanted to take it to the next level. Dermond was immediately all in.

“We’re talking about more than just a contextual project where we’re helping people become safer,” Dermond says. “The idea is bigger because the DeafBlind community is an underserved community. Bringing attention to this is a very, very important part of the project.”

Over the last few months, the team of Northeastern students expanded the scope of the project significantly. It’s still a bracelet, but it now uses Bluetooth technology instead of WiFi, giving it the same range with a longer battery life. The doorbell itself has a passcode-enabled keypad as well as a more traditional doorbell. And the whole system is designed with vibration variability, which is key to make the device more accessible for DeafBlind people.

“If this is somebody that is known at the door, it will vibrate in a certain pattern that the DeafBlind person would recognize … and they would feel safe to open [the door],” Dermond says. “If they got a package or somebody that they don’t know is at the door, the second scenario is [someone] would press the button if they don’t know the code, and the DeafBlind person would get a different [vibrating] pattern.”

The goal is to create a wearable device the size of an Apple Watch that doesn’t come with the Apple Watch price. Dermond says currently the bracelet and doorbell are functioning, but the remainder of the semester is all about making it cheaper, more comfortable and more functional for the DeafBlind community.

Every member of the team has had to learn new skills, some more than others. Scaperdas, who works on the electrical engineering side of the project, admits he came in with little experience when it comes to soldering or sourcing electronics.

“I already feel like I’ve learned so much,” Scaperdas says. “I concentrate in medical devices technically, so this is basically what I want to do out of school. … In my classes so far I’ve learned a lot of conceptual stuff, so it feels cool to actually be able to see it come to life in person and actually do that hands-on work that needs to go into it.”

It’s all in service of a project that Dermond hopes will leave an impact long after he’s graduated from Northeastern.

“This is the seed of an idea that can grow much bigger because this is an underserved community, and we see an opportunity to make change,” Dermond says. “That is why I’m super passionate about this project and I would consider this culmination of my whole Northeastern experience.”

Cody Mello-Klein is a Northeastern Global News reporter. Email him at c.mello-klein@northeastern.edu. Follow him on Twitter @Proelectioneer.