‘The practice was nowhere near the policy.’ History of segregation in Boston schools examined

Lindsa McIntyre, high school superintendent of Boston, describes the first high school she attended as an “annex.”

“The cafeteria served as the gymnasium. The windows were cracked, broken or peeling,” she said. “The books were old, the room was cold.”

McIntyre spoke about her experiences attending both segregated and desegregated Boston schools during a panel talk, “Racial Inequality and Struggle for Equity in the Boston Public School System,” on Wednesday at Blackman Auditorium on Northeastern’s Boston campus.

Part of the university’s Myra Kraft Open Classroom series, the panelists discussed school segregation and the fight for racial equality in the school system from the 19th century to the present. The panel talked about issues that Boston still faces today, issues that can be applied anywhere else.

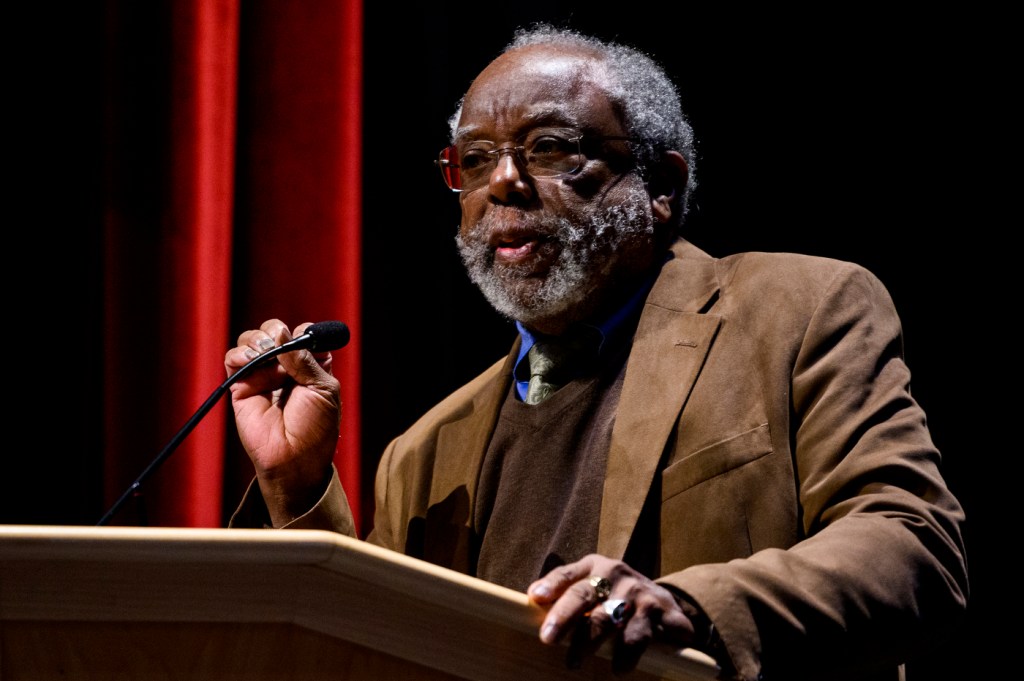

“What we have experienced in Boston takes place everywhere else in the world,” Northeastern distinguished professor and panel moderator Ted Landsmark said. “And as often as not it took place around who has access to education, and who doesn’t.”

Panelist Rev. Stephen Kendrick kicked things off with a little-known but consequential story from the 19th century.

He told the audience about Sarah, a 4-year-old Boston girl who in 1847 became the subject of a court case around school segregation. Sarah had to walk past several white schools to get to a Black school each morning. So her father, a printer named Benjamin Roberts, sued the city of Boston on her behalf.

Roberts v. City of Boston made it to the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, where the family ultimately lost—Sarah was denied access to white schools in 1850. The case would set the precedent for “separate but equal” in the United States, established by the Supreme Court in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896).

The case had other implications for the future, however: Attorney Charles Sumner’s argument that segregation had to end anticipated the Brown v. Board of Education decision. “He warned the whole nation that segregation had to be ended, or there was a dark future for all of us, together,” Kendrick said.

The case was part of a larger abolitionist movement in Boston, one that led to the peaceful desegregation of Boston schools in 1854. But, Kendrick warned, “The story is not over … in many ways, we have ground to make up.”

Over 100 years later, Boston would face another challenge in the form of the busing crisis. Those who watched the news at the time may remember images of violent encounters on the street. But, as Jim Vrabel, author of “A People’s History of the New Boston,” said, there was far more to it than that.

“History is more than images, as powerful as they are, and sometimes as accurate as they are,” he said. “History is also about decisions and details.”

By detailing the policy decisions that went into establishing court-mandated busing in Boston in 1974, Vrabel said, he illustrates that history could have taken a very different course.

“It’s not inevitable that desegregation and busing failed in Boston,” he said. “It might have succeeded, if individuals in positions of authority at the time … had done a better job. It might have worked. And instead of dividing the city and its people, it might have brought them together.”

“All of what we heard, I’ve experienced,” said McIntyre as she rounded out the panel. “The policy said, ‘desegregate.’ But the practice was nowhere near the policy, and it hurt. It hurt to raise your hand to want to answer a question that was asked by your teacher and to be invisible. It hurt to be ignored.”

McIntyre ended up going to a private high school, she said, but she returned to her local school for her final year and “found all my friends failing.” “They all had tremendous potential, but it was ignored or stifled,” she said.

She discussed how this experience informs how she approaches her current position as superintendent, from helping students to feel accepted, to making sure their needs and their safety is at the center, to making sure they are engaged in discourse, to bringing joy into the classroom.

“Our students have historically been marginalized, and traditionally been underserved,” she said. “Our mission around equity and action is to eliminate the achievement gap, to provide equitable and excellent student outcomes.”

In this way, history is informing the present and the future, something Vrabel emphasized in his talk.

“We still have trouble talking about it, but we must because we need to learn from history. Especially because history has a way of coming back around at us,” Vrabel said. “We need to learn from the lessons of the past mistakes of the past so we can confront the challenges of the present in the future.”

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.