How will Ukraine survive winter if Russia decides to ramp up infrastructure attacks?

As Russia partially withdrew its troops from the Kherson region in the south of Ukraine, Northeastern experts worry that President Vladimir Putin might return to attacking municipalities and critical infrastructure, pushing the power grid to a breaking point.

Russia announced on Nov. 9 that it would be withdrawing its troops from the Ukrainian city of Kherson and the west bank of the Dnipro River to protect the lives of civilians and “preserve the most important thing–the lives of our servicemen and the overall combat capability of the grouping of troops,” according to top military commander Gen. Sergey Surovikin.

Two days later, the Russian military completed the retreat from the area it had occupied since the early days of the invasion and that Russia formally declared its territory at the end of September.

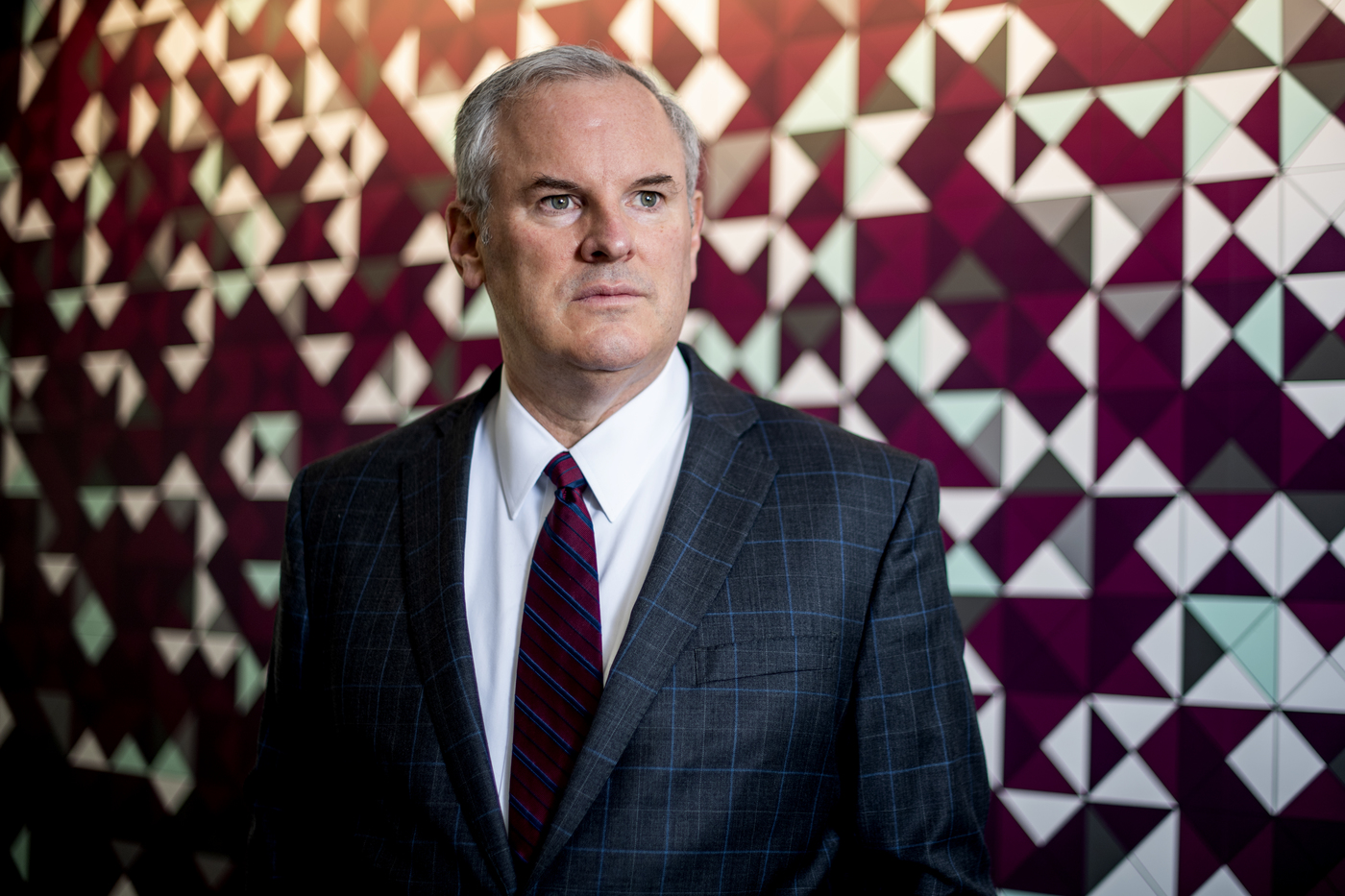

“It [the withdrawal] reflects the deteriorating ability of the Russian military forces to combat Ukrainian armed forces,” says Stephen Flynn, professor of political science and founding director of Global Resilience Institute at Northeastern University. “Now, it’s almost taken for granted that the Ukrainians are a far better fighting force than the Russian forces.”

However, this strategic setback may result in Russia stepping up its attacks on civilian infrastructure, he says, which it unleashed in October, using missiles and Iranian-made kamikaze drones to strike power plants and substations, cutting electricity, heat and water across several Ukrainian regions far from the front lines.

The line between a military target and a civilian target has always been blurred in large scale warfare, Flynn says.

“But what is certainly relatively new is using these drones, a relatively recent technology in terms of warfighting, to surgically attack civilian infrastructure,” he says. “In the U.S. context, a lot of our infrastructure is certainly vulnerable to that kind of attack as well.”

In the first part of the war, Russia was not targeting the civilian-critical infrastructure, because they expected a rather quick victory, Flynn says.

“They didn’t want to have to rebuild what they would have won,” he says.

As the war moved to a stalemate and even some reversals in the Russian military gains, Russia decided to weaken the resolve of Ukrainian people, especially, with winter approaching.

“If history is any judge though, that doesn’t really work very well,” Flynn says. “The notion here is that somehow the population will not support the war, when placed under duress. It almost always has the opposite result—the population becomes even more committed.”

Mai’a Cross, professor of political science, international affairs and diplomacy and director of the Center for International Affairs and World Cultures, views attacks on municipalities and infrastructure as a sign of desperation as Russia is not doing well in the war, she says.

“In order to be able to score some sense of a victory, Putin is essentially directing the military to target civilians, and particularly to try to damage infrastructure on a wide scale,” she says.

According to the Ukrainian authorities, Russian attacks destroyed 40% of the country’s energy supply system and affected 4.5 million people.

“Things could get pretty dire,” Flynn says. “In the wintertime, you are faced with likely needing to evacuate the cities.”

Destruction of the power grid does not just mean the inconvenience of the lights going out or refrigerators going idle, Flynn says. It snowballs and impacts all the other critical foundations that make for modern life.

Absence of power leads to lost supply of water and wastewater management issues that can affect the health of a city. It also affects telecommunications, most transit systems or electromechanical systems.

The damage puts at risk operation of gas lines, as compressor stations that push fuel down the line require power. The infrastructure distraction can further cause shortages of food and other supplies, Cross says. It already affected Ukraine’s revenue from electricity exports to neighboring countries along the country’s western border.

Currently, the Ukrainian government introduced rolling blackouts and is working on creating warming stations and places where people can go to stay safe and warm.

“There’ll be limits to what they can do with that,” Flynn says. “The open question is when will Russia push the energy infrastructure to the breaking point? It’s obviously very close now.”

The International Monetary Fund, European politicians, and G-7 diplomats promised to help Ukraine protect and fix its infrastructure to avoid disaster. Flynn says it is not entirely certain how much the European countries can help, given the short timeline before winter. Plus, the European equipment has to align with the equipment that Ukrainians have, which sometimes is older.

If Russia continues to attack the substations and the other key points to the power grid, the West won’t probably be able to keep pace with the destruction, Flynn says.

Due to Russia cutting off natural gas and other disruptions to supplies to Europe, there’ll be a lot less energy products around for sale, Flynn says, which will translate into higher energy prices. Europe might face rolling blackouts this winter as well.

“As we’re seeing in our home, in the U.S. context, when gas prices go up, it has some political implications,” Flynn says.

So far, most of the countries nearest to Ukraine can imagine themselves in Ukraine’s position, he says. They are willing to make some sacrifices in order to avoid the worst-case scenario of Russia expanding itself further, should Ukraine fail.

“As you get further away from the front line, then it becomes more of an issue,” Flynn says.

Change in the makeup of the U.S. Congress in 2023 may have some impact on the level of U.S. support, as well, which has a potential to cause a domino effect in that commitment by European countries, he says.

Cross is more optimistic.

“I do firmly believe that Western powers, the United States, Europe and other countries beyond that will continue to stand by Ukraine, and they will do everything in their power to prevent Ukraine from losing,” she says. “I don’t think that support is going to go away.”

A failure of Ukraine in this war is basically not an option for the West, she says. Although the West had no motivation to get into some kind of conflict with Russia, at this point it is about a response to Russian aggression in the region to discourage Putin from attacking another country next.

“Ukraine is an important Western ally that will, from now on [and] indefinitely into the future, look towards the West as the home of its future trajectory,” she says, noting that this war is symbolic of a greater clash between authoritarian powers that seek to destroy democratic powers and the meaning of the liberal international order.

Getting through the winter will be challenging, but it is doable, Cross says.

“Sending over civilian experts who can help repair infrastructure is something that actually the EU has quite a bit of experience with,” Cross says.

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.