Stroke survivor empowered by Fetterman, but Northeastern expert says campaign missed opportunity to raise awareness

Early in his post-stroke recovery, Kevin Bowen, 75, of Dedham, Massachusetts, overheard someone saying, “Oh, isn’t that sad that the fellow can’t speak.”

The person was talking about Bowen, a Vietnam War veteran, a poet and a former director of the William Joiner Center for the Study of War and Social Consequences at the University of Massachusetts.

“I couldn’t speak, I was enormously frustrated because of that,” Bowen says. “And I was ready to hit him.”

The stroke locked Bowen “in the prison house of language,” he says.

Bowen suffered the stroke in March 2019 after a planned surgery on his left carotid artery at Massachusetts General Hospital. His brain was deprived of oxygen for quite a while, he says.

“I was largely unable to function after the surgery. I don’t remember much,” Bowen says about the first five months of his life post-stroke.

He spent almost a year in the hospital and various rehabilitation facilities before he was able to go home.

The damage done to his body was extensive: Bowen has partial vision loss, his right arm is paralyzed, and he lost sensation in his right leg. He spends a lot of time in a wheelchair, although he is practicing to walk in a brace.

Bowen has done a lot of physical and speech therapy. But it took him years to find out that his problems with language had a name—aphasia, an acquired communication disorder that impairs a person’s ability to process language, but does not affect their intelligence.

Today, Bowen can converse both in-person and on the phone, despite some lingering language difficulties, which makes him very sympathetic to the struggle of John Fetterman, who won the U.S. Senate seat in Pennsylvania in the 2022 midterm elections despite concerns over his health.

Fetterman suffered a stroke in May 2022, days before the Pennsylvania primaries. He chose to continue the race, saying that he did not suffer any cognitive damage in a statement issued from Penn Medicine Lancaster General Hospital. However, after an interview with NBC in October and a debate with his Republican opponent Mehmet Oz, it became apparent that Fetterman had trouble processing speech and expressing his thoughts.

“I can relate to almost all of that, all of the things that have to do with speech,” Bowen says. “Being unable to articulate, that must be really frustrating for a man with the intellect of John Fetterman.”

Bowen points out that Fetterman has made a remarkable recovery in only five months and can speak better than him. He says he admires Fetterman for his determination to continue with the race.

“I am heartened by it. I am empowered by it,” Bowen says. “It is great to spread awareness of different people’s situations [after a stroke].”

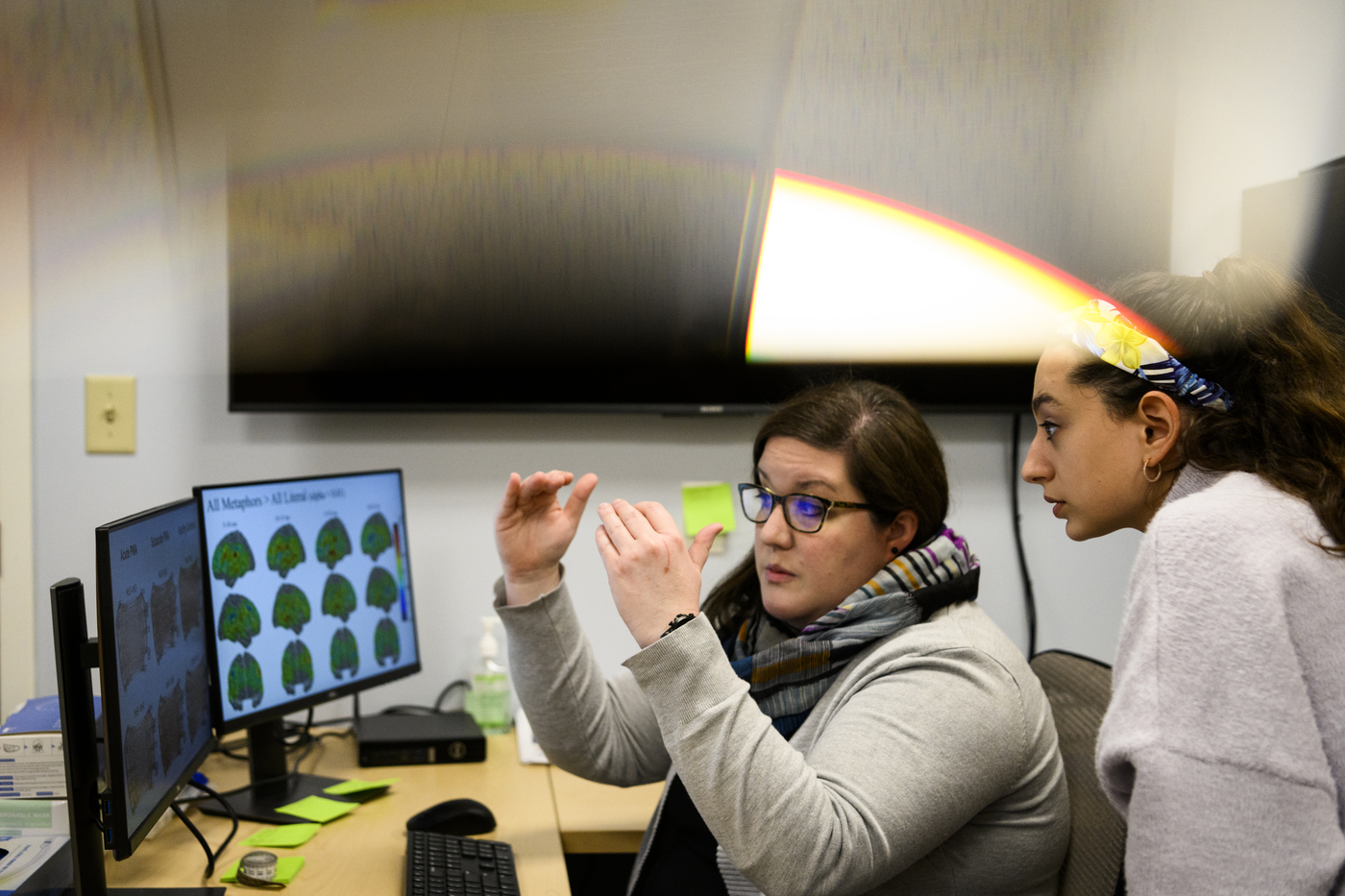

When Bowen learned that he had aphasia, he enrolled in a study program at Northeastern conducted by Erin Meier, assistant professor at Bouvé College of Health Sciences and director of The Aphasia Network Lab.

Meier believes that Fetterman has aphasia and by choosing to call his condition “an auditory processing disorder,” his campaign team might have missed an opportunity to educate the public and raise awareness that “aphasia is loss of language, not intellect,” she says.

“In all my years working clinically, I would never call that an auditory processing disorder,” Meier says. “It’s ‘You have spoken language deficits, which is part of your aphasia.’”

According to the National Aphasia Association, more than 2 million Americans have this disorder. It is one of the most common consequences of a stroke in the left hemisphere of the brain, Meier says, which for most people is a more language dominant area, but not many people have that word in their lexicon.

Besides stroke, aphasia can manifest itself after a traumatic brain injury, Meier says. There is also a progressive form of aphasia, a type of dementia that has an insidious, or gradual, onset and gets worse over time. Meier suspects that this is what the actor Bruce Willis has.

“For many stroke survivors, it is the opposite,” she says. “You recover over time.”

The most recovery after a stroke happens in the first six months, but people can continue to improve drastically well into the chronic phase of recovery after six months to years after stroke.

The unfortunate situation with Fetterman, Meier says, is that people are not used to seeing someone struggle with understanding what they are hearing or taking time to come up with words, or occasionally using the wrong word, especially, a politician whose bread and butter is his language and speaking.

Meier finds inspiring the fact that Fetterman has publicly acknowledged his stroke and is persevering.

“I think that messaging is really important and the fact that somebody can have a stroke and can return to a job that is really challenging,” she says.

He is not doing the work in a vacuum, though, she says. His team has found strategies that work for him. While Fetterman’s spoken language comprehension is impacted, he is using written language comprehension with closed captioning as a buoy.

“Having those kinds of strategies and being able to use them effectively is one path where somebody could certainly have a really hard job [like] being a politician and succeed at it and still have this disorder,” Meier says.

There has been more acceptance for people with disabilities in politics, Meier says, as U.S. Rep. Tammy Duckworth, D-Illinois, who lost her legs and partial use of her right arm in 2004 while deployed in Iraq, became the first woman with a disability elected to Congress. But voters mostly expect a senator to be able to walk, talk and move like an able-bodied person would do, she says.

Fetterman’s disorder is not well understood and invisible compared to a physical disability, Meier says. She doesn’t blame people who were concerned about his ability to do the job because of the lack of understanding about how our higher order thinking skills are represented in the brain.

“But at the same time, it’s just kind of a sad thing for our society that there’s not more variety between the folks who we have in political office in terms of their ableness,” she says.

As for Bowen, he continues to work on his speech and walking. He is aware that being a veteran provided him with access to a lot of opportunities through the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. He worries about people who founder without health insurance and proper resources for recovery from a stroke or aphasia.

Bowen attends a book club in which 18 stroke survivors read news, fiction, nonfiction books and discuss opportunities for research participation. At home, when he is not reading, he listens to podcasts, practices Buddhism, watches birds in the side garden and spends time with his wife, Leslie Bowen, and their two dogs.

“My wife is a miracle worker. I can’t say enough for how much she has encouraged me and has given me every opportunity to grow, and she is basically my inspiration,” Bowen says. “This is the reason I keep going and living with aphasia. People without aphasia cannot appreciate how deeply affected your soul can be and you have to reach down hard to lift yourself up again and that’s a struggle but it is worth it.”

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.