Will an opposition leader emerge in Iran protests? Outrage over injustice defies violent crackdowns

Despite violent crackdowns, anti-government protests in Iran continue to persist.

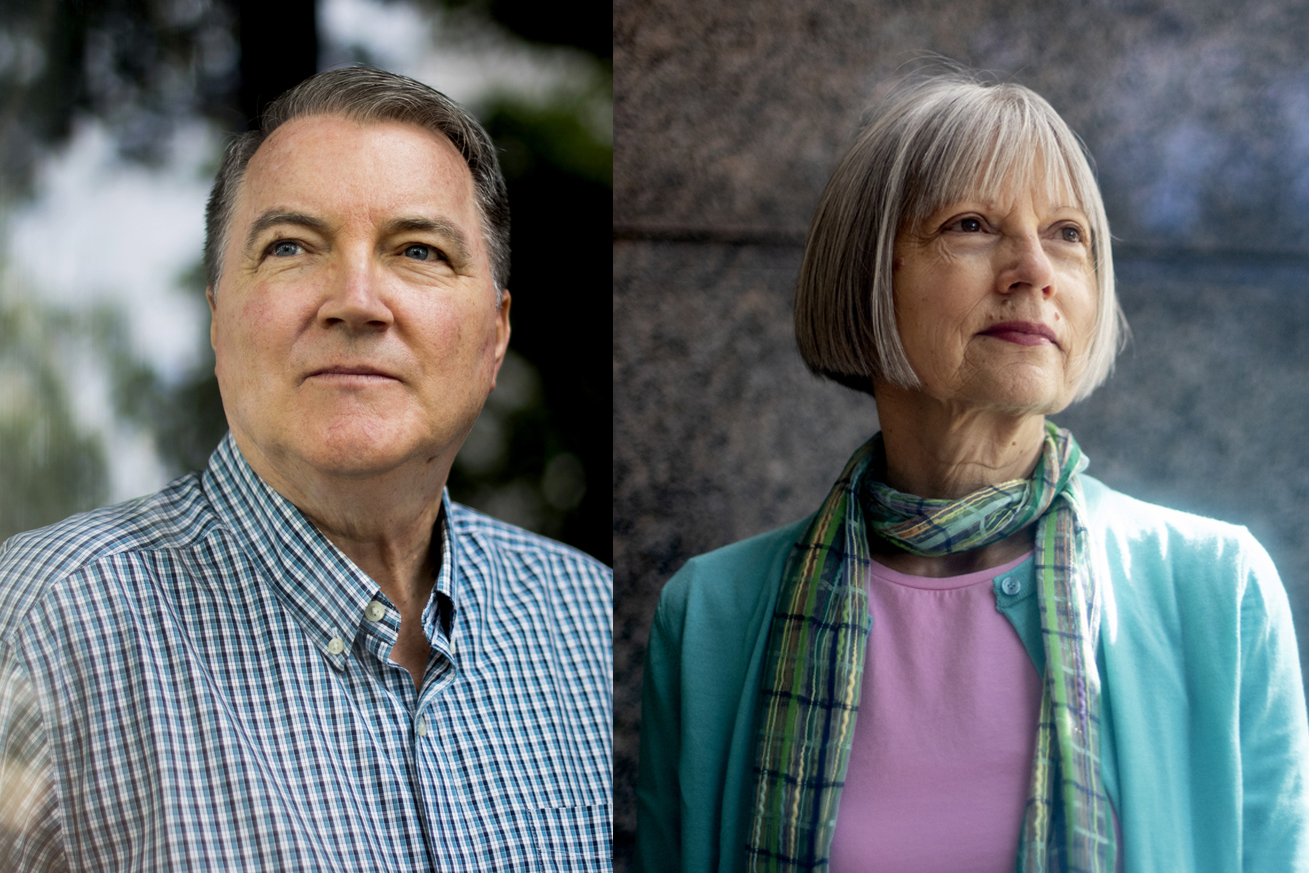

As country-wide demonstrations enter the fourth consecutive week, Northeastern University experts weigh in on the regime’s uncompromising response, the role of students who joined the protests at the beginning of October, and what is important for any protests to succeed.

There appears to be no organizing force or leadership behind the current Iranian protests, says Gordana Rabrenovic, associate professor of sociology and director of the Brudnick Center on Violence and Conflict at Northeastern, and that could be problematic in terms of accomplishing change.

“Protest by itself doesn’t mean you are going to be successful,” she says.

To achieve change, protesters need to build a movement with infrastructure, goals and strategies for moving from dissatisfaction to transformation, she says. They need to understand exactly what they want to get out of the protests, what will happen if they win, and how the transformation should take place.

Protests are a collective action that allows people to express their agency and grievances by coming together, Rabrenovic says.

The more people with similar concerns join in, the more visible the issues become. Participation in a protest reassures people that they are not alone, Rabrenovic says.

The 2022 protests in Iran started on Sept. 17. They were ignited by the outrage of Iranian women over the death of a 22-year-old Kurdish woman, Mahsa Amini, in police custody after she was detained on Sept. 13 for allegedly violating the country’s hijab (headscarf) rules.

Since then, the protests have spread across the country, social classes, religious groups and gender. In the third week, students at more than 20 universities across the country and even high school students joined in, according to the Iran Human Rights organization, based in Norway.

Iranian students protest out of the sense of righteous duty, says Denis Sullivan, professor of political science and international affairs at Northeastern.

“It is this sense of outrage over injustice that they take to heart and act upon, perhaps, even more readily than their elders do,” Sullivan says. “They feel obligated to right the wrongs of the society, especially the wrongs that come down on their generation.”

Amini was one of them, Sullivan says.

“They don’t want to live like this another year,” he says, whether it is due to economic collapse, a stolen election or the religious police “who are just brutal and murderous. If not now, when?”

This is not the first time Iranian students united to protest against the government of the Islamic Republic of Iran. Students widely engaged in the protests against the shah (the king of Iran) in 1977 and during the Iranian revolution of 1978-1979. But the demands of students have not been met after the revolution, when the IRI was established and Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the first supreme leader, came to power, Sullivan says.

In July 1999, student protests, or so-called “student movement,” grew into the most violent demonstrations in the early history of IRI ignited by the closure of the country’s leading reformist newspaper Salam and further restrictions on the freedom of speech. After that, major protests erupted in Iran every 10 years, in 2009 and 2019, Sullivan says, and students were always a part of them.

When joining the protests, individuals weigh the cost of participation versus the cost of non-participation, Rabrenovic says. Sometimes the cost of participation can be imprisonment or even death.

Some might argue that young people, especially students, have less to lose by participating in protests than older, working people with families. But in some societies the cost of non-participation is also high, Rabrenovic says.

In those types of situations a person might be thinking, “I am going to be killed doing nothing. [If I protest] at least I am going to be killed doing something,” she says. If someone’s life is in danger no matter what, then action becomes empowering and gives them a sense of agency.

The Iranian government chose to condemn the protests and use violent, relentless force to stop them from the very beginning. Video clips and photographs posted on social networks online as well as protesters’ accounts of the events show that the security forces are using live ammunition, tear gas, anti-riot water cannon trucks and violent arrests.

At least 185 people, including women and children, have been killed across 17 provinces of Iran, according to the Iran Human Rights, while the Women Committee of the National Council of Resistance of Iran reports as many as 400 killed and 20,000 arrested.

Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, expressed his full support of the security forces, claiming last Monday that the unrest had been instigated by foreign powers, including the U.S. and Israel. He blamed protesters for the violence.

“The ones who attack the police are leaving Iranian citizens defenseless against thugs, robbers and extortionists,” he said.

That is why, Rabrenovic says, it is really important for any protests to be nonviolent. The moment protesters turn to violence or respond to a provocation from the government forces, it is easier for the regime to justify using violence against them to “preserve order.”

Violence by governmental forces is used to show power and to deter more people from participation, Rabrenovic says. But it is also bad for public relations as it shows the government in a bad light.

The regime’s violence can legitimize the demands of the protesters in the eyes of the domestic audience and the international community, which is happening in Iran’s case.

On Oct. 3, President Joe Biden announced that the U.S. will be imposing further costs on perpetrators of violence against peaceful protestors. The U.S. is facilitating Iranians with access to the Internet, Biden said, and will hold accountable Iranian officials and entities like the morality police for employing violence to suppress civil society.

The European Union is also expected to decide on sanctions on Oct. 17, according to Reuters.

Protesters need to organize and establish what they want to happen, Rabrenovic says. Toppling the regime is not the end result, she says. If there is no clear understanding of what’s next, some group with their own agenda might hijack the movement for their own benefit.

The regime might also give promises and an appearance of change, she says, but in reality everything will stay the same.

It is hard to predict what the current protests in Iran will lead to, Sullivan says.

He believes that the first sign of the protests succeeding would be when the security forces stop killing people against the explicit orders of the regime to crack down on them.

“That’s how the Shah fell, basically, when it became too much for the Iranian military just to kill people in 1978-1979,” Sullivan says.

The Iranian regime currently has the upper hand due to the sheer amount of power, force and violence it uses against the demonstrators, Sullivan says.

“The only thing I would probably predict is that it won’t take another 10 years for them [protests] to come back,” Sullivan says. “Even if they are stopped now, they’ll continue again at some other point.”

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.