How the Jim Crow South encouraged racial policing by those with ‘no legal authority’

If a Black person wanted to ride a public bus in the Jim Crow-era South, they would have to climb into the front of the bus to pay, then exit the bus and walk to the rear entrance.

Segregation, codified under the South’s so-called Jim Crow laws, meant that Black passengers couldn’t even walk through the white section at the front of the bus.

And the white bus driver making sure passengers used the correct entrance? He might very well be carrying a firearm.

“Jim Crow was the legal system of the Southern states for at least 60 years. Jim Crow was the law,” says Northeastern University Distinguished Professor of Law Margaret Burnham.

But the enforcement of Jim Crow wasn’t just entrusted to what we would consider traditional law enforcement today.

“It was actually enforced by individuals who had no legal authority, but who were nevertheless recognized as proper enforcers of Jim Crow norms and rules,” Burnham says.

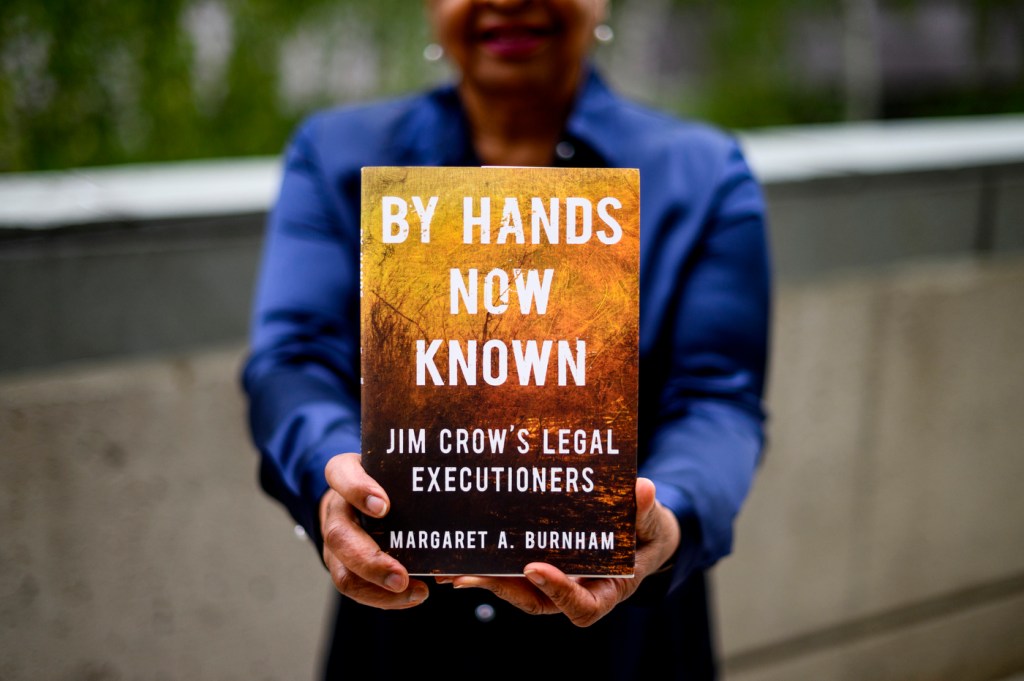

In her new book, “By Hands Now Known: Jim Crow’s Legal Executioners,” Burnham looks at how the standard responsibilities of white bus drivers, teachers, librarians and many others included monitoring the Black public for violations of Jim Crow laws and ensuring the continuation of segregated practices.

The violation of these segregated, racist norms often meant violence against Black people, and the machine of Jim Crow—sometimes legislated, sometimes condoned through inaction—would reinforce the idea that any white person could commit racially motivated violence with impunity.

While this isn’t a new argument, Burnham says, “By Hands Now Known” looks at the problem with new historical evidence, much of which comes from the Civil Rights and Restorative Justice Project, which Burnham also founded and directs.

“By Hands Now Known” begins by investigating cases that involve the rendition of escaped slaves: When an enslaved person would escape from a state in the South to a state where slavery had been abolished (or had never been legal), legal battles would break out over which state had authority.

Burnham draws a line from these pre-abolition cases to similar cases in the 20th century, when individuals accused of committing a crime in the violently anti-Black South would cross into states without the same Jim Crow legislation.

These “latter-day” runaways, if returned to the South, “would either face extralegal violence or court proceedings that would be unjust,” Burnham says.

Another example Burnham provides regards the effective decriminalization of kidnapping, at least when it came to white perpetrators and Black victims.

The legal standing of the South, Burnham says, was that the Black body was “subject to the will of white directives.”

In the wake of these oppressive laws, which encouraged a kind of “quotidian violence,” a national Black, legally informed community came together, a community that included lawyers, activists and everyday people.

Burnham uses these stories of Black resistance, especially from the 1940s and early 1950s (before the classic Civil Rights era, which began in 1954), “to illustrate the depth and character of resistance during this time,” she says.

Burnham closes the book by presenting the debate for repair, redress and reparations. The chapter makes a “contemporary imperative to address past wrongdoings, especially where judicial proceedings are no longer available” or possible, Burnham says.

Burnham’s hope for the book is to make visible this living history for the communities that have been touched by it, “in whatever way is best suited to engage in discourse and memorialization and repair,” she says.

“By Hands Now Known” has already received a Publisher’s Weekly star and is a finalist for the 2022 Kirkus Prize in nonfiction. The book comes out on Sept. 27, and Burnham will begin her book tour that night at the Brattle Theatre, in Cambridge, Mass.

The Civil Rights and Restorative Justice Project will have a public launch, with a celebration and conference, on Oct. 6-7.

The book will join other tools that communities can use to engage in conversations around the United States’ violent history, reparations and where to go from here.

While the Civil Rights Movement achieved some important milestones in the name of equality, Burnham says that the inequities that it sought to address have persisted in the long haul. “Now we have the facts,” she continues. “The question is, what does it mean for us today?”

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.