Now banned by TikTok and others, Andrew Tate rode wave of online misogyny, says Northeastern expert

As summer break ends and students return to their desks, some teachers have noticed a disturbing trend.

“Andrew Tate has made his debut in my class,” wrote one teacher on Reddit. “I hear some nonsense about women cheating more than men and the young man cited ‘Dr. Tate.'”

“The rise of Andrew Tate is ruining my freshman boys,” wrote another teacher. “They’re addicted to his content. Just this week I had to have 6 convos with families about their sons saying shit like ‘women are inferior to men’ [and] ‘women belong in the kitchen Ms____.'”

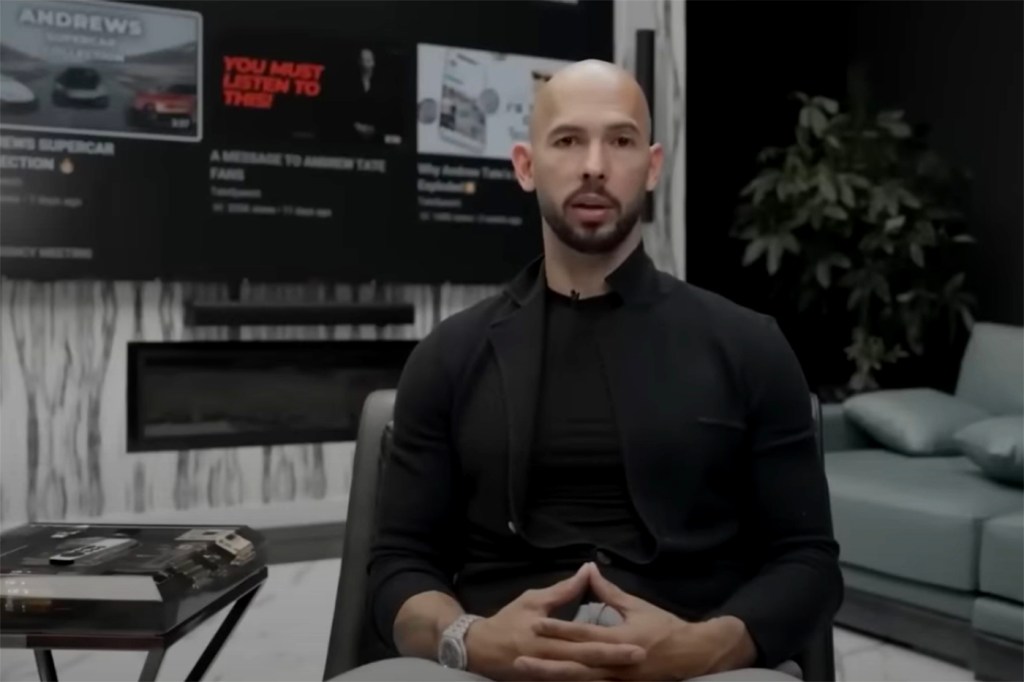

Tate, a British-American social media influencer, is well known for making misogynistic comments in his videos, which have been removed from TikTok but at one point had billions of views. In the videos, Tate referred to women as property, described how he would attack a woman who accused him of cheating, and said he doesn’t believe that depression is real (Tate says his comments were taken out of context).

Following a public outcry, last week he was banned from YouTube, TikTok and Facebook. But experts say that Tate is not acting in a silo; in fact, online misogyny has been on the rise for years, and social media platforms are not built to handle it.

Tate’s rise to online prominence began in 2016, when the former kickboxer appeared on the reality TV show “Big Brother.” He was removed after a video emerged of him hitting a woman with a belt (he says the encounter was consensual).

In 2017, Tate was banned from Twitter for the first time when he said that women should “bare [sic] some responsibility” for rape. Now, his bans have become so widespread that they’ve become a meme. However, copycat accounts and fan accounts still spread his messages, and Tate has moved on to other social media platforms.

How did Andrew Tate get such a large following? His rhetoric is actually part of a trend, says Margo Lindauer, director of Northeastern Law’s Domestic Violence Clinic. Lindauer says that misogyny has been growing online over the past decade, but especially in the last six years. The #MeToo movement, which gained prominence in 2017, may have something to do with this.

“A lot more women gained the confidence to speak about their truth and assert their own power,” she says, “and I think a lot of cisgender men felt very vulnerable.”

Economic insecurity may also be a factor that draws some men to influencers like Tate, says Brooke Foucault Welles, associate professor at Northeastern’s College of Arts, Media and Design. “If men are meant to believe that their value in society is being providers, and you enter a time of real economic distress, which I think we’re in right now, then men start to feel like they’re losing their value,” she says.

As an influencer, Tate’s lifestyle offers an enticing alternative. On his website, Tate refers to himself as a “World Champion Kickboxer & Multi-Millionaire.” The website shows the muscular Tate driving convertibles, shooting guns, stepping off a plane onto the tarmac, riding a Jet Ski, and laying out on a yacht. In one video on the site, he blows cigar smoke in a woman’s face.

Tate offers to teach other men to mirror his lifestyle on his website. “I grew up broke and now I am a multi millionaire. I teach the deserving the secrets to modern wealth creation,” it reads. Before it was shut down this month, participants paid $49.99 a month for the Tate-founded Hustler’s University, which brands itself as an “online money-focused community providing education and coaching,” that was taught by 12 “multi-millionaires,” though none of the teachers listed have last names or clear job descriptions. The site encourages men of any age to join. Followers earned money through referrals, prompting speculation that it was a pyramid scheme, something Tate denies.

Tate’s misogynistic rhetoric does not take center-stage on the website or in most of his posts. However, even if the promise of wealth and prosperity, and not his attitudes toward women, is what brought people to his content, those messages still come through, Lindauer says. “They’re getting it no matter what,” she says.

Lindauer compares him to former president Donald Trump and how his lifestyle has become aspirational for some, despite his rhetoric and how it translates to harm he has allegedly committed against women. Tate, for his part, is under investigation by Romanian authorities for human trafficking and rape, The Guardian reports; he denies the allegations.

“What’s being exalted is really problematic,” Lindauer says.

Unfortunately, Welles says, “there’s evidence that it works. When you can exploit some group that is less powerful than you in society, it does in fact work to make you more economically successful.”

It’s not surprising that Tate’s message was able to spread on social media; in fact, platforms like TikTok are the perfect place for it to thrive due in part to their origins.

“We know that communication media of all kinds, but particularly online media like social media platforms, are predominantly designed by and for men,” says Welles.

While four out of nine members of Meta’s board of directors are women, only two out of eight members of the management team are women, and just over a third of all employees were women in 2021. In the tech industry as a whole, meanwhile, women make up just over a quarter of the workforce.

“I don’t think that many people at these organizations set out to create toxic, misogynistic places,” Welles says. Still, the absence of diversity at every level of an organization makes it more likely that there will be oversights when it comes to protecting vulnerable users, she says.

Instead, platforms become safe spaces for people spreading messages of hate. “When we decide not to protect women or trans folk, or people of color, whoever it is that we’re not protecting, we’re implicitly making a choice to protect someone else,” Welles says. “So someone else’s user experience is more valuable than the people that we’re choosing not to intervene for.”

The sophisticated algorithms that customize each user’s experience may exacerbate this problem; as one Guardian investigation found, TikTok’s algorithm may make it more likely for young men to see misogynistic posts. Interaction with a post makes it likely that more like it will appear in the future.

But isn’t this all just talk?

Lindauer says no. “I think it absolutely has real-world consequences,” Lindauer says. “There’s an explosion of misogyny in all facets of the internet that can be incredibly toxic and very harmful because it absolutely has consequences in terms of how people relate to one another, how people speak to one another, how people treat one another.”

Violent social media content can be especially harmful for young people who are learning how to navigate relationships for the first time, and may be out of practice with socializing due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Plus, young people are particularly susceptible to messaging: The prefrontal cortex of the brain is not fully developed until 25, Lindauer says, meaning images are more likely to stick. And when images and messages are repeated, they are more likely to be perceived as facts, says Welles.

But, Lindauer says, social media platforms do not consistently take responsibility for content, despite the fact that feeds are heavily customized. “Are these sites just platforms like they argue, or are they more responsible for the information they’re sharing?” she says.

If screening content worked more like copyrighting, Welles says, this would go a long way. Copyright protection is generally very fast and efficient: if a clip from “Game of Thrones” is used in a TikTok video, it doesn’t take long for it to be taken down. But for misogynistic content, “It’s just not a priority in the same kind of way,” Welles says. If it were, and people who are abusive on the internet were banned, and content was screened, it could help give educators and parents more time to have conversations with young people.

Of course, fixing social media doesn’t get rid of misogyny. “I would love to be able to say yes, if we just lock down or figure out the social media problem, then misogyny, racism, and homophobia would go away, but that’s not true,” Welles says.

And banning Tate doesn’t get rid of misogyny on the internet. As one teacher wrote on Reddit, “the kids will forget him quickly enough and we will have another fly to swat.”

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.