Will the FDA’s proposed nicotine regulation spell the end for smoking in the US?

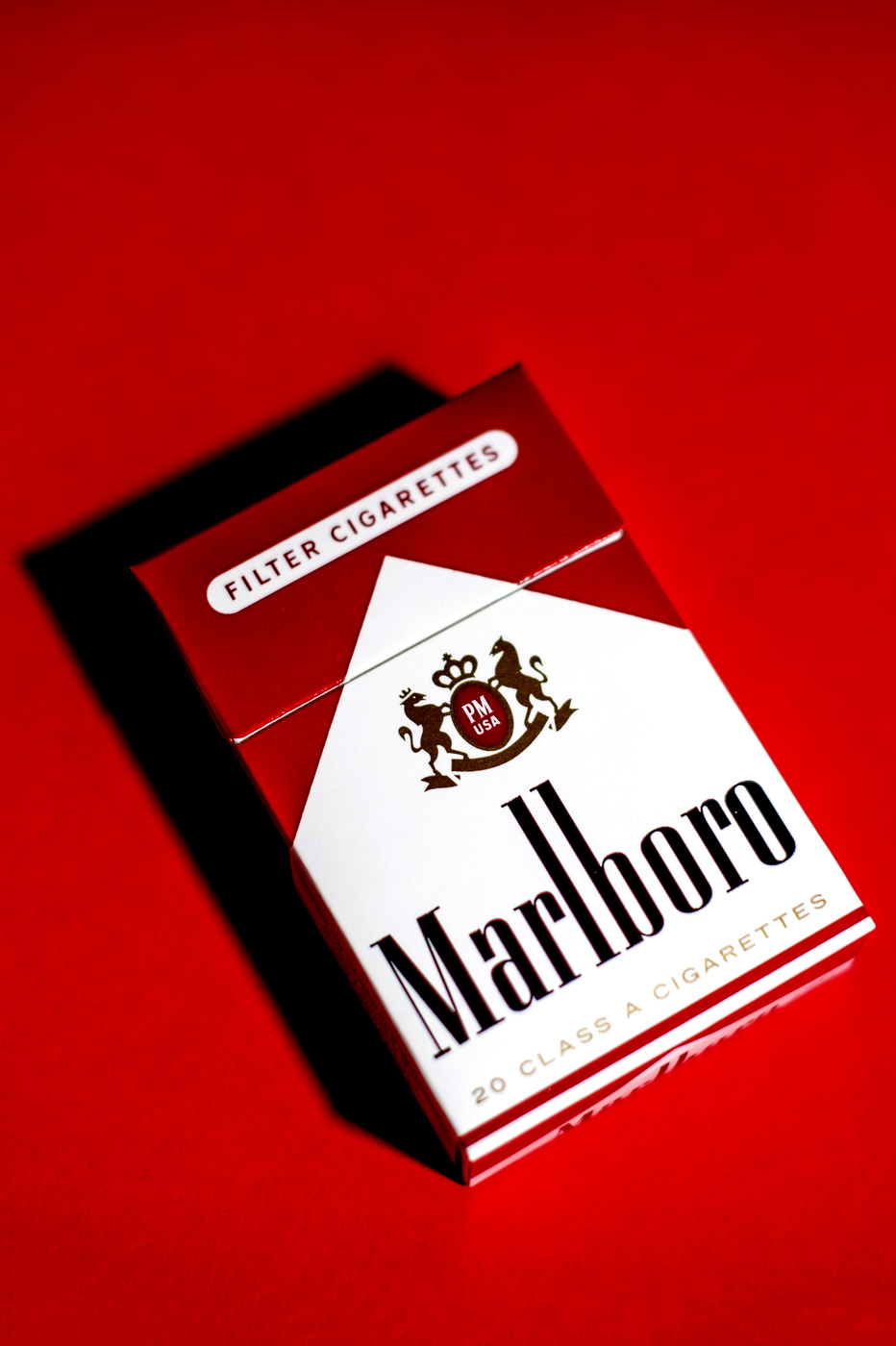

Earlier this month, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration proposed regulations that would establish a maximum nicotine level for cigarettes and other tobacco products.

By requiring companies to reduce nicotine in cigarettes to non-addictive levels, the regulation would be one of the most significant efforts to reduce smoking in the U.S. in decades and would deal a significant blow to the $95 billion tobacco industry.

“Nicotine is powerfully addictive,” Robert Califf, commissioner of the FDA, said in a statement. “Lowering nicotine levels to minimally addictive or non-addictive levels would decrease the likelihood that future generations of young people become addicted to cigarettes and help more currently addicted smokers to quit.”

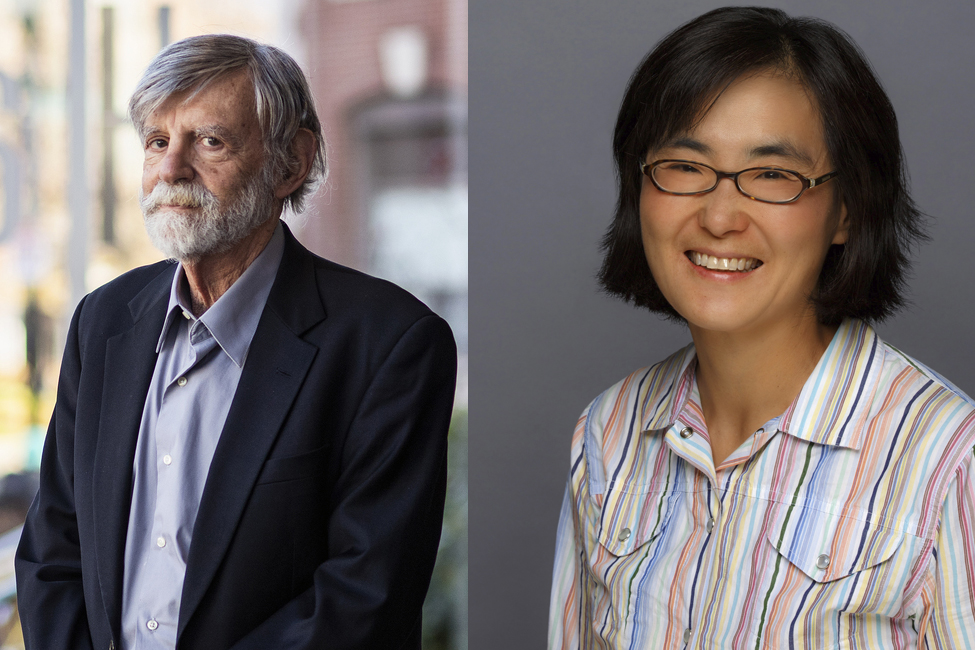

The FDA has stated its intent to issue the rule by May 2023, but the process of adopting a rule like this requires a years-long process of public comments and courtroom action. Richard Daynard, Northeastern distinguished professor of law, anticipates the proposal will become law by 2027, but he says the tobacco industry will not go down without a fight.

“They ain’t gonna like it,” Daynard says of the cigarette companies.

“Cigarette companies, their initial response is, ‘Well, it’s not really a cigarette. Nobody will smoke the damn things,’” says Daynard, who has been engaged in tobacco litigation for years and now serves as president of the Public Health Advocacy Institute at Northeastern. “Well, that may be true, but the question is do they have a right to sell a dangerous, deadly, addictive product on the theory that if it’s not dangerous, deadly and addictive nobody will use it? I don’t think that’s a good argument.”

Although nicotine itself is not directly responsible for cancer or lung disease––those are the result of carcinogens released by the combustion of the tobacco leaf––the highly addictive nature of nicotine keeps people smoking, increasing their risk of negative side effects. According to the FDA, smoking is the leading cause of preventable disease and death in the U.S. Every year, 480,000 people die prematurely from a disease related to smoking, more than AIDS, alcohol, illegal drug use, homicide, suicide and motor vehicle crashes combined, according to the FDA.

“This is a truly game-changing proposal that would accelerate declines in smoking and save millions of lives from cancer and other tobacco-related diseases,” Matthew Myers, the president of Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, said in a statement. “But these gains will only be realized if the Administration and the FDA demonstrate a full-throated commitment to finalizing and implementing this proposal.”

The number of smokers in the U.S. has been on the decline, and by slashing nicotine levels, the FDA hopes that number will decrease even further––and it has good reason to believe it will work.

FDA-funded research found that smokers who used cigarettes with 95% less nicotine than a normal cigarette, which contains 10 to 15 milligrams of nicotine per gram of tobacco, smoked fewer cigarettes and became less dependent. They were also more likely to try quitting, which about 55% of adult smokers currently attempt to do, according to the FDA. Only 4 to 7% are successful. The FDA is not at the stage where it has announced what the maximum nicotine level would be, but the World Health Organization has found that cigarettes with 1 to 2 milligrams per gram of tobacco are minimally addictive.

“Cigarettes are the most addictive out of all the nicotine delivery systems,” says Miki Hong, assistant adjunct professor of public health and health equity at Mills College, which is expected to merge with Northeastern on July 1. “It’s a big deal because if they limit the amount of nicotine, [cigarettes] won’t be as addictive. And if they’re not as addictive, then, ultimately, it comes down to profit because that will mean less cigarettes smoked, [more] lives saved and, ultimately, less profit for tobacco companies.”

The research, which was published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2018, projected that by 2100, if the regulations were adopted, more than 33 million people would avoid becoming regular smokers and there would be about 8 million fewer tobacco-related deaths.

But reducing nicotine levels in traditional cigarettes is not the only tactic the FDA needs to take in order to combat smoking. The tobacco industry has made marketing, designing and selling cigarettes into an art, Hong says, and companies have found ways to target every conceivable market.

“These products, these nicotine delivery systems, these cigarettes, they’ve been specifically designed, engineered and marketed to enhance the addiction,” Hong says. “They’ve gone into overdrive creating the perfect cigarette for every single market they can think of for their profit. When you take that nicotine away from all the markets, what’s going to be left for them?”

The FDA is already looking to outright ban menthol cigarettes, which represent more than a third of cigarette sales in the U.S. menthol cigarettes also accounted for 81% of the cigarettes used by Black smokers in 2020 and have been “culturally tailored” for Black communities, Hong says. Menthol’s minty taste, aroma and cooling sensation eases irritation in the mouth and throat, making them easier to smoke, especially for young people and first-time smokers. The most recent U.S. surgeon general’s report revealed that 87% of adult smokers start smoking before they are 18 years old.

At the same time, the FDA is focused on cracking down on e-cigarette use. Earlier this month, the FDA rejected e-cigarette maker Juul’s application to sell its products and ordered the vaping company to take its products off the U.S. market. Juul appealed the FDA’s decision in a federal appeals court and won a temporary stay.

Daynard predicts the tobacco industry will fight tooth and nail at every step of the process to stop the FDA from passing these regulations. He says companies will likely use some of the same arguments they have been using for years: that such a drop in nicotine levels will force smokers to go cold turkey, preventing smokers from making a choice to quit.

“Their defense in legal litigation is often, ‘The smoker made a choice [to smoke],’” Daynard says. “Well, OK, anybody who keeps smoking their cigarettes [after this regulation is passed] will actually be making choices. The idea that ‘Oh my god, you can’t take away the nicotine because that gives smokers the ability to make a choice’ is not going to sound very good.”

The FDA will have to contend with a billion-dollar industry that is constantly lobbying policymakers and concocting new ways to sell to smokers, but Hong says the regulation is worth fighting for. Likening it to the first statewide indoor smoking bans, Hong says the FDA’s latest regulation would make a seismic impact on the country’s public health.

“When they made that shift between second-hand smoke exposure in the workplace and restaurants … back then it was a big deal to inconvenience the smokers,” Hong says. “It’s the same idea. The fallout will be significant from this nicotine lowering [policy].”

For media inquiries, please contact Shannon Nargi at s.nargi@northeastern.edu or 617-373-5718.