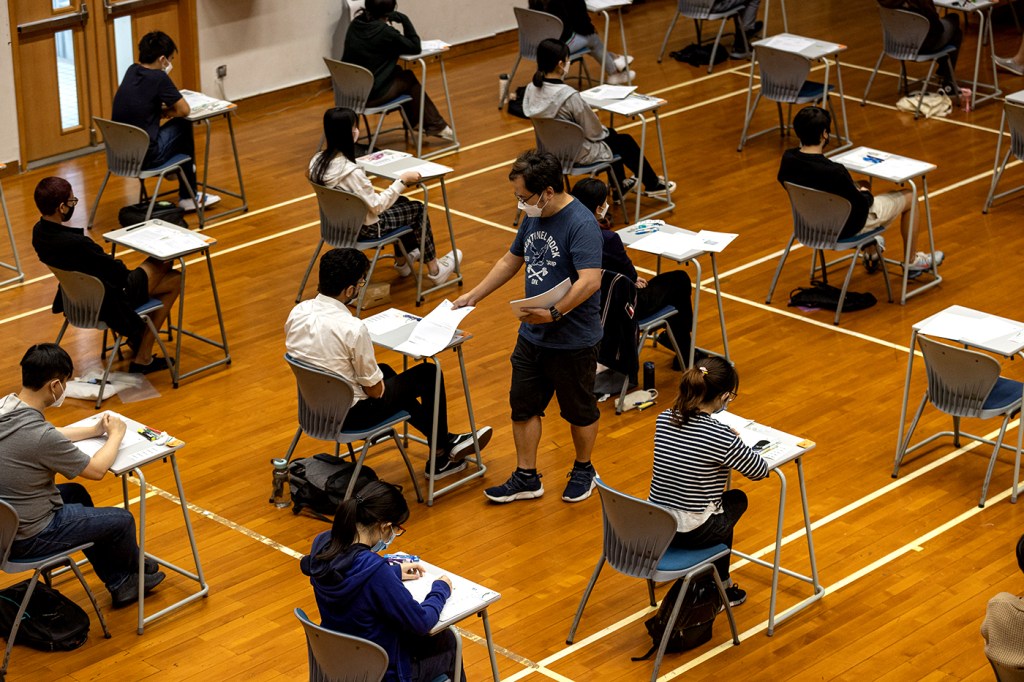

New textbooks will teach that Hong Kong was never a British colony. Is China trying to rewrite history?

Hong Kong is preparing to roll out new textbooks that will teach students that the city was never a colony of the British Empire, the New York Times reports. Northeastern experts say that by revisiting the interpretation of Hong Kong’s British past, China is not trying to rewrite history, but rather reassert something that has always been true for the Chinese government: Hong Kong is a part of sovereign China.

“There is a lot of interpretation in history,” says Philip Thai, director of Asian studies and a historian of modern China and modern East Asia.

While modern American scholars have moved toward writing a more inclusive history, which incorporates various perspectives and is not as cut and dry, the Chinese government is pushing a state-centered narrative, Thai says, which is: British Hong Kong has always been illegitimate; Hong Kong was occupied by the British, but it was never a colony.

This overarching position of Beijing is not new, says Xuechen Chen, assistant professor in politics and international relations at Northeastern’s New College of the Humanities in London. It is supported by the fact that after the People’s Republic of China (PRC) became a UN member in 1971, it successfully lobbied for the removal of Hong Kong and Macao, a Portuguese territory from 1557 to 1999, from the UN’s list of colonies in 1972. The removal prevented them from stepping on the pathway to self-determination brought about by the UN’s 1960 Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples.

As a result, the PRC can claim that if Hong Kong was a colony, it should have remained recognized in the UN declaration to have an opportunity for self-determination, Thai says. Since Hong Kong was removed from the declaration, it was never a colony but rather a territory occupied by the British; thus, it has always belonged to China.

The understanding that Hong Kong is an integral part of China delegitimizes not only what the British had done there, but also delegitimizes any protest for more rights, more self-determination, or any alternative interpretation of laws that differs from the Chinese government’s, Thai says. As a result, it supports the PRC’s handling of Hong Kong protests in 2014 and 2019.

The official position of the PRC is that due to a misunderstanding of Hong Kong’s British past, modern Hong Kong society is disordered and confused, Thai says; to fix it, China has to assert the truth as defined by the Chinese Communist Party. That is why China has been making greater efforts internally to consolidate and reinforce the ruling party’s legitimacy, Chen says, especially since 2019.

Chen also notes an external shift in China’s self-image.

“Even a decade ago, China used to highlight its semi-colonial past to build up its international identity as part of the Third World or as part of the developing countries that really suffered from the imperial past,” Chen says.

China used to present itself as a victim of imperialism and foreign intervention that was experiencing a national rejuvenation after centuries of humiliation. However, the implementation of new textbooks demonstrates an incremental shift in China’s domestic narrative and international identity, Chen says.

“As China gains more economic and political weight in regional and international affairs, China starts to see itself as a big power, as a great power,” Chen says. “[It] no longer wants to emphasize this identity as a norm taker, as a weak kind of international actor, or as a victim in global affairs. What China wants to do is to create a more coherent narrative, both internally and also externally.”

Although the U.S., U.K. or other European countries may perceive reports about Hong Kong textbooks as some kind of concerning signal, Chen says, they also should try to understand why this is happening and look into a more nuanced position from Beijing.

“China has consistently emphasized the principle and the norms of respect for sovereignty,” Chen says.

There has been an ongoing debate and concern in the West around human rights or the democratization process in Hong Kong, Chen says, but from a Chinese normative perspective its handling of domestic issues should be respected because of its sovereignty.

Thai shares the same sentiment, saying that national sovereignty will always trump any international agreement for the Chinese government, including the Sino-British Joint Declaration, under which the British government agreed to transfer Hong Kong to China in 1997 on the condition that the social and economic systems would remain unchanged for 50 years.

At the same time, the PRC argues that it has been “unswervingly” implementing the “One Country, Two Systems” policy since 1997, under which people of Hong Kong have enjoyed a high degree of autonomy.

“Practice has fully proven that One Country, Two Systems is the best institutional arrangement for Hong Kong’s long-term prosperity and stability,” reads an op-ed published on June 20 online in People’s Daily, the largest state-run newspaper. “The Central Government will continue to ensure that the policy of One Country, Two Systems remains unchanged, is unwaveringly upheld, and in practice is not bent or distorted.”

There has also been a shift in how Europe approaches China, Chen says. During her research, she has noticed that in the 1990s or early 2000s Hong Kong issues were barely mentioned in official documents and press releases in the context of China relations. In recent years, the E.U. and U.K. keep flagging Hong Kong issues to create more pressure on China, Chen says.

“There has been a trend of politicization,” Chen says. “In many cases, the Hong Kong issue and also the whole situation in Xinjiang has been actually used as a bargaining chip.”

If Western countries previously hoped to transform the PRC with multilateral or bilateral trade deals into a democratic country long-term, these days they seem to have realized that that was an illusion, Chen says.

“They no longer have such kind of hope—to transform China,” Chen says. “And that basically made many Western countries adopt a hostile and much more aggressive stance on these issues. But to what extent [can] they really resolve the problem?”

Chen points out that there has definitely been a deterioration of relations between China and Europe in the past few years. She believes that Western countries are concerned that the expansion of China’s political influence will eventually create a fundamental threat to the Western-dominated liberal, democratic international order.

It remains to be seen whether the divergence between the West and China will keep growing. But the real tragedy, Chen says, is that Hong Kong is trapped between the two sides, and the city and its citizens have lost their own agency in this narrative.

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.