What’s changed since abortion rights were last before the Supreme Court?

Legal experts are all but certain that the U.S. Supreme Court is poised to cut back or even strike down abortion rights in its review of Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization this term and render a decision that could prove to be among the court’s most consequential in decades.

During the presidency of Donald Trump, conservatives added Justices Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett to the bench, shifting the high court’s ideology firmly to the right. Now, with a 6-3 conservative supermajority, the court appears ready to dismantle Roe v. Wade, which established that people have a constitutionally protected right to an abortion.

It’s not the first time a conservative-led bench threatened to restrict abortion rights. Notably, parts of Roe v. Wade were upheld in Planned Parenthood v. Casey in 1992—the first time the landmark 1973 decision was directly challenged. But then, as now, advocates and legal experts contend that Roe’s core holding is in grave danger. And some experts argue that the 1992 ruling signaled the impermanence and eventual dismantling of abortion rights.

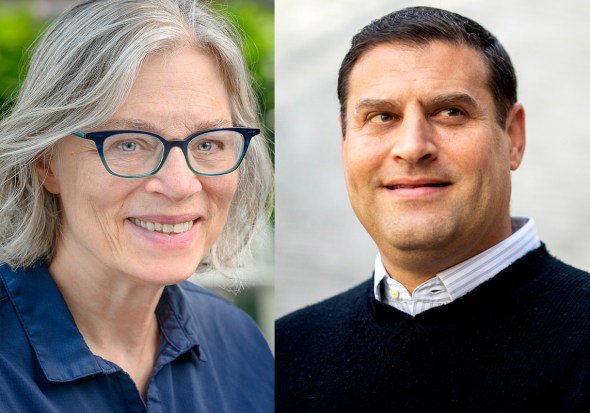

Left to right: Distinguished Professor of Law and Associate Dean for Experiential Education at Northeastern, Martha Davis; and Daniel Urman, director of hybrid and online programs in the School of Law, and director of the Law and Public Policy minor. Courtesy photo and Photo by Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University

“We all expected that Roe would be overturned” then, says Martha F. Davis, university distinguished professor of law at Northeastern, who teaches constitutional law and human-rights advocacy. “And in fact, people talk about the end of Roe now, but Roe ended in Planned Parenthood v. Casey, as far as I’m concerned.”

Instead of overturning Roe, the court in Planned Parenthood v. Casey established an “undue burden standard” used to assess state abortion laws. The court’s opinion, authored by Republican-appointed justices Sandra Day O’Connor, Anthony Kennedy, and David Souter, preserved Roe’s “essential holding” while making it easier for states to impose restrictions. Justice John Paul Stevens and Harry Blackmun, both of whom were in favor of striking down the state law, signed on to the compromise, creating a majority opinion.

As expected, the decision did pave the way for more draconian state abortion laws, Davis says.

“We knew, following the ruling, that this standard was not going to be particularly protective” of abortion rights, Davis says.

There was good reason to think Roe wouldn’t survive the 1992 challenge, which scrutinized a Pennsylvania abortion law that required women seeking abortions to, among other things, obtain consent from their husbands, and which implemented a 24-hour waiting period before the procedure. Anti-abortion activists believed they would be handed a decisive victory, not least because eight of the nine justices on the bench at the time had been appointed by Republican presidents.

But that’s not what happened. Although the Rehnquist Court—legal wonks often refer to Supreme Court cohorts by the chief justice’s name—upheld most of the restrictions imposed under the Pennsylvania law, it reaffirmed that women have a right to an abortion before fetal viability without undue interference from the state. Davis says the decision came as a surprise to many reproductive-rights advocates.

“The way it survived was stare decisis,” or the principle that courts adhere to precedent, Davis says.

What shocked observers about the ruling was Kennedy’s siding with O’Connor and Souter, many have said. Chief Justice William Rehnquist and associate justices Clarence Thomas, Antonin Scalia, and Byron White dissented, expressing a desire to see Roe overturned.

But the Casey decision hardly put an end to the abortion debate in U.S. In some ways, it only emboldened anti-abortion activists, whose persistence—thanks to the rise of the evangelical right—elevated the cause into the main platform of the Republican Party, where it can still be found in phrases such as “culture of life.”

Thirty years later, Republicans have another conservative supermajority, engineered this time to avoid the kinds of surprise compromises that justices on the Rehnquist Court managed to concoct, says Dan Urman, who teaches constitutional law and the modern U.S. Supreme Court at Northeastern.

“I really think that the biggest change [since 1992] has been the careful vetting by the Republican Party of judges,” Urman says. “That those five justices voted the way they did was cause for the Republican Party’s taking judicial nominations even more seriously today.”

That kind of judicial vetting has now given the Republican Party an opportunity to overrule Roe in the case challenging a Mississippi abortion ban. Justice Kavanaugh has suggested as much, even after pointing out that Casey was “precedent on precedent” during his controversial confirmation hearing.

The conservatives “probably have five votes from justices who don’t care about precedent anymore,” Davis says. “However, ignoring precedent would strike a blow to the legitimacy of the court for years to come.”

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.