Should I report my at-home COVID-19 test results?

With hundreds of millions of free rapid-result COVID-19 tests being mailed out to homes, a common question people are asking is: Am I required to report a positive result to local health authorities?

No, says the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, but the federal agency recommends that people isolate and inform their health-care providers. Some states, such as Washington, have set up a reporting hotline, while local health departments such as Marin County, California, and Tompkins County, New York, have online self-reporting forms.

Washington, D.C.’s health department also has an iPhone feature and Android app.

But a newly released national survey of nearly 11,000 people finds that 31% of those who tested positive at home for the virus that causes COVID-19 did not follow up with a more accurate polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test at their doctor’s office or a testing facility, and thus are likely not captured in official data.

‘Younger people are engaging in more interactive behaviors, and they are at lower risk of dying if they get sick, but they are at higher risk of getting sick,’ says David Lazer, distinguished professor of political science and computer science. Photo by Adam Glanzman/Northeastern University

Researchers discovered that hours-long waits for testing coupled with the fact that some health-care facilities actually discouraged people from coming in are some of the causes for people not following through.

Still, wouldn’t it be better if the government had more accurate data on positive case counts? Yes, says David Lazer, university distinguished professor of political science and computer science at Northeastern, and one of the study’s authors, but the data was already messed up to begin with.

“Early in the pandemic, people who were sick couldn’t get tested at all, and there were a lot of asymptomatic people,” he says. “Better information is better for sure, but our data was already so screwed up.”

The fact that nearly 3 in 10 people didn’t report their positive results didn’t faze Lazer. “I was surprised that it wasn’t higher, honestly,” he says. For one thing, antigen tests tend to lean toward a false negative—meaning someone has the virus but the test didn’t pick it up. For peace of mind, some people may choose to visit a testing facility or a doctor.

“They end up testing positive at the doctor’s office and then they enter into the official system that way,” he says.

The U.S. study was conducted nationally by the Covid States Project, a collaborative effort by researchers from Northeastern, Harvard, Northwestern, and Rutgers universities The online poll lasted about a month, starting shortly after Christmas during the omicron surge.

Home antigen tests flew off pharmacy shelves as an alternative to standing in hours-long lines at local testing sites for PCR tests, results of which can come back from a lab in a day or two—sometimes longer.

Among those who did get a follow-up test, 88% received confirmation of a positive result while 12% got a negative result. Researchers noted in the study that they did not distinguish between antigen or PCR testing in the subsequent test, so they couldn’t estimate what proportion of the 12% might have indicated that the original test was a false positive.

Thus, it is possible that both results could be correct.

With the prevalence of skewed data, the study calculated that official counts may underestimate positive COVID-19 cases by about 6%, partially alleviating concerns that official case counts are only capturing the tip of the iceberg because of the growing prevalence of home testing.

“I expected that figure to be higher,” Lazer says. He thought that rapid tests would be more common than going to the doctor or a testing facility. In fact, antigen tests have been used less as a proportion of all tests because they’re expensive, he adds.

Hundreds of millions of free tests have begun heading out to people’s homes under a plan announced by President Joe Biden. The U.S. went from 24 million home rapid tests on the market in August to 375 million in January, according to the White House.

Their use is particularly frequent with people 18 to 24 years old, city dwellers, Democrats, and the well-educated, the Northeastern study found.

Researchers surmise that younger people just don’t go to the doctor as much and are more inclined to favor home tests. Higher usage among young adults also could be traced to the possibility that the coronavirus has been spreading more among younger people, or that they’re more likely to be exposed to it.

“In general younger people are engaging in more interactive behaviors, and they are at lower risk of dying if they get sick, but they are at higher risk of getting sick,” Lazer says.

On the flip side, people 65 years and older were least likely to use home tests, as were Republicans, and rural residents.

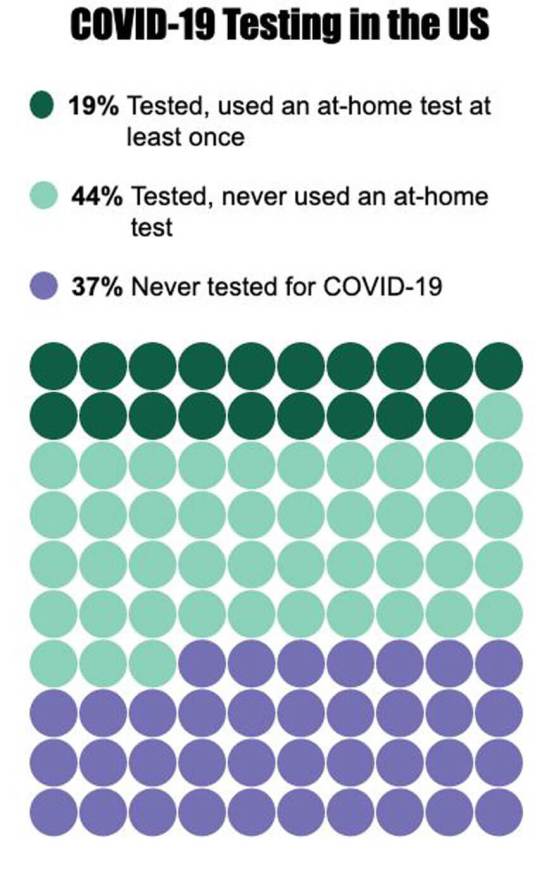

In all, 19% of survey-takers used a home test at least once, but that is expected to ramp up sharply in the weeks ahead, Lazer predicts.

Nearly two years into the pandemic, researchers hit upon a key finding—37% of people said they had never taken a COVID-19 test of any sort, antigen or PCR. This was most prevalent among men, Asian Americans and white people, rural residents, and people 45 years and older, the study found.

“I was really surprised that so many older people haven’t been tested given they’re at higher risk,” says Lazer. It raises questions about access and overall attitudes about getting tested, he adds. “There’s a good chunk of the country in general that doesn’t go to the doctor unless absolutely necessary because it’s a big sociological and psychological barrier.”

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.