80 years after Pearl Harbor, US and Japan show how enemies become allies

On the 80th anniversary of the Pearl Harbor attack, which launched the U.S. into World War II after years of isolationism, the memory of the event “still has an important and maybe even a renewed significance today,” says Risa Kitagawa, an assistant professor of political science and international affairs at Northeastern.

Assistant Professor of Political Science and International Affairs Risa Kitagawa

“Moments of crisis … are profoundly ripe for fear and moral outrage and anger to turn into fear mongering and paranoia,” she says. Kitagawa notes that after Pearl Harbor, Japanese Americans—many of whom were U.S. citizens—were seen as an “internal enemy,” forced from their homes and interned in prison camps for the duration of the war. It wasn’t until 1988 that the U.S. formally apologized to the Japanese Americans who had been treated that way, including those who were drafted or volunteered to fight for the U.S. in Europe during World War II.

Fears of danger from outsiders have emerged at other times in U.S. history, too, including after 9/11, during the Trump administration’s efforts to create a so-called “Muslim ban,” and during an uptick in anti-Asian crimes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Concerns about similar stereotyping arose as recently as last month, when the appearance of the omicron variant of the coronavirus prompted some countries, including the U.S., to ban travel from southern Africa.

As communities and countries seek healing from such xenophobia, perhaps the reconciliation—albeit delayed—after Pearl Harbor can serve as example.

Eighty years after an attack intended to cripple not only the U.S. military but also public morale, “these two countries form one of the strongest alliances” in the world, reinforced by economic cooperation and mutual geopolitical interests in east Asia, says Kitagawa, who studies how governments’ apologies affect public opinion, both in their own nations and around the world.

In October, a statement from President Joe Biden called the alliance between the U.S. and Japan “the cornerstone of peace, security, and prosperity in the Indo-Pacific and the world.”

“These historical grievances don’t disappear overnight,” Kitagawa observes. But she says that improved relations can be “built on generations of political work [and] also generations of public opinion” shifting to accept collaboration, and even friendship, among former enemies.

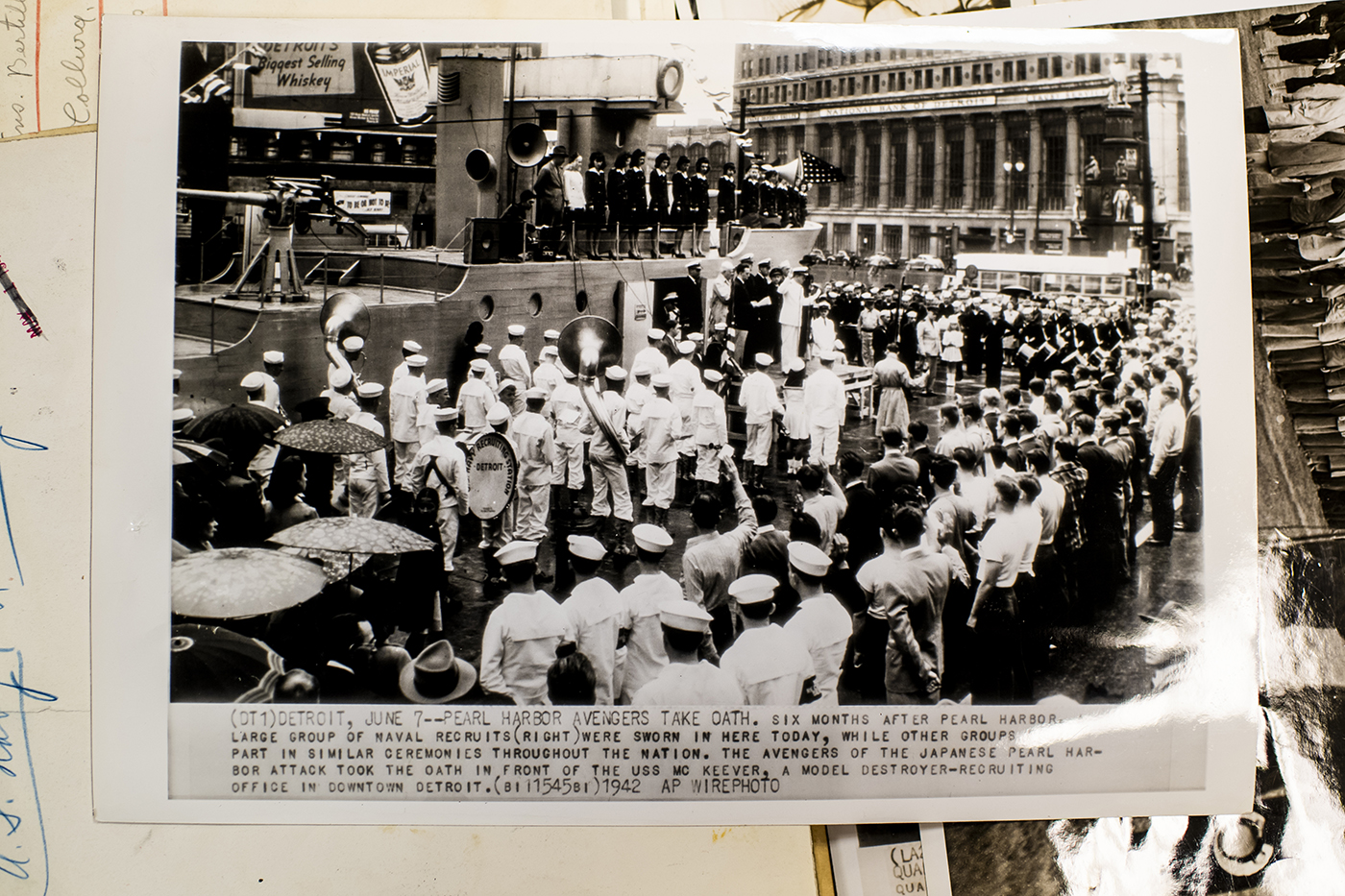

At Pearl Harbor this year, about 30 survivors, reportedly in their late 90s or older—including one who is 101—are expected to attend a service slated to include a moment of silence at 7:55 a.m., the time the attack started, in memory of the more than 2,400 U.S. servicemembers and civilians killed that day.

In a proclamation declaring Dec. 7 National Pearl Harbor Remembrance Day, Biden recognized those who died, those who fought in the war that followed, and pledged to “carry[] forth the ensuing peace and reconciliation that brought a better future for our world.”

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.