The Push for Facebook Regulation Gathers Momentum

Since Frances Haugen, a former Facebook employee, came forward with troubling information about the far-reaching harms caused by the company’s algorithms, talk of potential regulatory reforms has only intensified.

There is now wide agreement among experts and politicians that regulatory changes are needed to protect users, particularly young children and girls, who are vulnerable to mental health problems and body image issues that are tied to the social media platform’s algorithms. Several changes have been bandied about, from amendments to Section 230 of the federal Communications Decency Act—the law that governs liability among service providers, including the internet—to transparency mandates that would give external experts access to the inner workings of tech companies like Facebook.

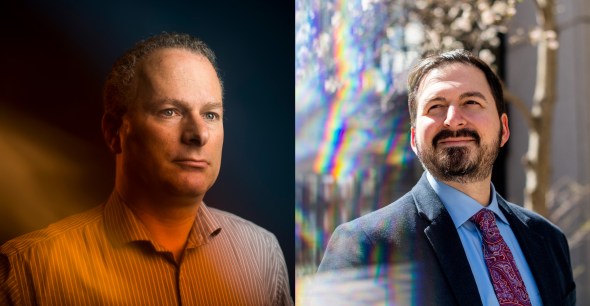

David Lazer, distinguished professor of political science and computer and information science, and Woodrow Hartzog, professor with joint appointments in the School of Law and the College of Computer and Information Science, pose for portraits. Photos by Adam Glanzman/Northeastern University and Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University

But, given the expectation of free speech online, lawmakers will have to get creative. One potential solution is to create a new federal agency charged with regulating the social media companies, as was done with the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, but it raises questions about how the political process, and the parties’ different ideas about privacy and free speech, would come to bear on such an effort, say several Northeastern experts.

“I wonder whether the parties would ever agree to create a special agency, or to augment the [Federal Communications Commission] in ways that provide more regulatory power to the federal government,” says David Lazer, university distinguished professor of political science and computer sciences at Northeastern.

A new agency could help offload some of the regulatory burdens facing the Federal Trade Commission, but it might also prove to be a dangerous political weapon that neither party would want the other to have, Lazer says.

Either way, there needs to be “more mechanisms to make Facebook more transparent,” he says.

“The problem is, once you have transparency, everyone sees something different,” Lazer says.

Testifying before Congress last week, Haugen helped shed light on how Facebook, which also owns Instagram and WhatsApp, devised algorithms that promoted hateful, damaging, and problematic content at the expense of its users. Documents Haugen shared with the Wall Street Journal last month showed that the tech giant knew its algorithms were harmful from internal research, but chose to keep the information secret.

Over the weekend, a top Facebook executive said the company supports allowing regulators access to its algorithms—and greater transparency more broadly.

It’s important to “demystify” how these technologies, which have been hidden behind a veil of secrecy for years, actually work, says Woodrow Hartzog, a law and computer science professor who specializes in data protection and privacy.

It’s been known for years, for example, that Facebook’s algorithms amplify, or optimize for, content that generates outrage. Revelations in the Wall Street Journal showed that Facebook’s own research has shown that its Instagram algorithms feed insecurity and contribute to mental health problems, promoting content that glorifies eating disorders, for example, to young female users.

Rather than ban algorithmic amplification, Hartzog says there should be mandated safeguards that monitor the deleterious effects of the juiced algorithms, adding “there are such things as safe algorithms.” The real question, he says, is can we have safe algorithmic amplification?

“They should be obligated to act in ways that do not conflict with our safety and well-being,” Hartzog says. “That’s one way we could approach this problem that won’t outright prohibit algorithmic amplification.”

Hartzog also suggested that regulators could draw on the concept of fiduciary responsibility, and impose “duties of care, confidentiality, and loyalty” on the tech companies, similar to the duties doctors, lawyers, and accountants are bound by vis-à-vis their clients and patients—only here it would be in relation to end users.

The problem lies with the financial incentives, Hartzog argues, which is why the idea of making the tech companies into “information fiduciaries” has gained traction. State and federal lawmakers are examining the information fiduciary model in legislation under review.

“What I would like to see come out of this… is a deeper and broader conversation about how to fundamentally change the incentives that are driving all sorts of harmful behavior related to the collection and use of private information,” Hartzog says.

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.