Why do we need booster shots for COVID-19 vaccines?

Booster shots are coming.

Top U.S. public health officials announced on Wednesday that booster shots of both the Moderna and the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccines would become available the week of Sept. 20, starting 8 months after a patient’s second dose. The Biden administration and public health officials say the decision to encourage coronavirus booster shots was made after reviewing data showing that vaccine-produced immunity to milder infection decreases over time.

Although officials expect that a booster shot will be needed for the single-dose Johnson & Johnson vaccine, it was originally authorized for emergency use later than the two-dose vaccines and so officials are still reviewing long-term efficacy data.

“You want to stay ahead of the virus,” White House medical adviser Anthony S. Fauci said during a news briefing Wednesday. “You don’t want to find yourself behind playing catch up.”

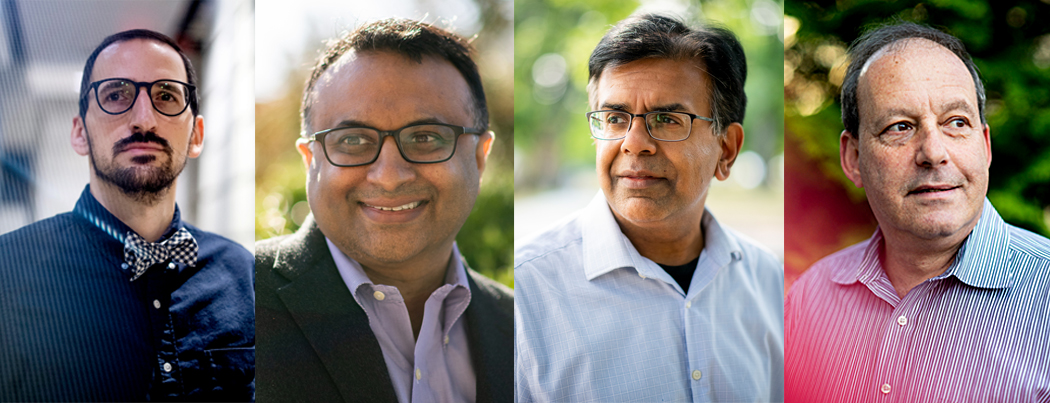

The news does not come as a surprise to public health experts such as Neil Maniar, professor of public health practice, associate chair of the department of health sciences, and director of the master of public health program at Northeastern.

“One of the hallmarks of the approach to addressing the pandemic,” he says, “is that as we get new information, as the data provides new clues and a new direction in terms of what we need to do, we have to then respond accordingly. The boosters are just another step in that process.”

Three research studies reveal that vaccine protections against SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, began to decline in the middle of the summer when the Delta variant was sweeping through the nation. Those reports, published Wednesday in the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s scientific digest, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, swayed the Biden administration to develop a plan for booster doses.

“Examining numerous cohorts through the end of July and early August, three points are now very clear,” CDC director Rochelle Walensky said at a news briefing Wednesday. “First, vaccine-induced protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection begins to decrease over time. Second, vaccine effectiveness against severe disease, hospitalization, and death remains relatively high. And third, vaccine effectiveness is generally decreased against the Delta variant.”

So what can a booster shot of the same vaccine do to boost someone’s immunity?

The mRNA vaccines work in two ways, explains Mansoor Amiji, university distinguished professor of pharmaceutical sciences and chemical engineering at Northeastern. First, it teaches the body to produce antibodies to block the virus from attaching to and infecting a cell.

“The second part is what’s called a cellular response, which makes our immune cells almost soldier-like in that if they see a virus-infected cell in our body, they go after that cell and kill that cell so that the virus from that infected cell cannot infect other cells.”

But over time, the concentration of those antibodies goes down. That is typical in biology, Amiji says. At the same time, variants are emerging that might look a bit different than the original virus that the vaccine taught the body to attack. So those antibodies might not be as good at blocking the variants from infecting the cell.

Booster shots of the same vaccine can still help, Amiji says. That’s because if you produce more antibodies, even if they aren’t as good at attaching themselves to the virus, a bunch of antibodies together can still coat the viral particle to prevent it from attaching to the cell.

Antibodies circulating in the body aren’t the only way that a vaccinated body generates immunity, however, says Todd Brown, vice chair of the Department of Pharmacy and Health Systems at Northeastern. There are immune cells that can remember the recipe to generate antibodies. If a person is infected with the virus, and those memory cells recognize it from when the vaccine trained them, then the immune system will start making more antibodies.

But, Brown says, those memory cells don’t work as well in older people. The new booster shot plan specifically articulates the need to administer booster shots to nursing home residents and other seniors.

The trio of studies published by the CDC show that vaccines do continue to be effective in reducing the risk of severe disease, hospitalization and death. The vast majority of so-called breakthrough cases, in which fully vaccinated individuals test positive for COVID-19, have been mild or asymptomatic.

That has led some experts—including officials with the World Health Organization—to criticize Biden’s move toward booster shots for the already vaccinated population while so many people around the globe remain waiting for even a first shot.

“I think it’s coming from good intentions. It certainly does boost antibody levels and there’s likely to be little harm,” says Brandon Dionne, associate clinical professor of pharmacy and health systems sciences at Northeastern. “The bigger question is, what’s our goal?”

“We have enough vaccine stockpiled in the U.S. right now to give people a third booster dose. But I don’t think that’s necessarily the most effective use of the vaccine,” he says. “I think the bigger bang for your buck is going to be finding a way to get those people [who are unvaccinated or partially vaccinated] vaccinated” in order to prevent hospitalization and deaths, and further reduce the spread of the virus around the world.

Timing may be part of the calculus behind Wednesday’s announcement, suggests Brown.

“There’s going to be some lag time,” he says, between when public health officials are sure that immunity from the vaccines wanes significantly enough over time to justify booster shots, and when those booster shots “actually go into people’s arms.” As the original vaccine rollout showed, the logistics of vaccinating such a large population can take time.

“The CDC is clearly trying to be one step ahead and has taken this as a preemptive measure,” Brown says. “The CDC is in a little bit of a tough situation where they want to rely on data to formulate and justify their recommendations, but if they wait too long, then people are going to die needlessly.”

That’s not to say efforts to vaccinate the unvaccinated should stop, says Maniar. “We want to reduce as much as possible the proportion of the population that is susceptible to the virus,” he says, and that means maintaining immunity in the already vaccinated population as well as increasing immunity in the unvaccinated or partially vaccinated population around the world. “We need to do both.”

For media inquiries, please contact Marirose Sartoretto at m.sartoretto@northeastern.edu or 617-373-5718.