What’s driving inflation? Prices for goods and services just hit a 13-year high.

U.S. prices for goods and services, which include everything from washing machines to car repair, grew in June at the fastest pace in 13 years as the economic recovery from the pandemic plowed ahead, according to the latest reading of the Labor Department’s Consumer Price Index. Excluding the food and energy sectors, where prices tend to fluctuate often, prices rose the most in 30 years. What’s going on? Why does everything seem so expensive?

News@Northeastern spoke with Paul Chiou, associate professor of finance, to find out.

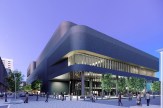

The prices of items such as cars may come back down to Earth when the microchip shortage is alleviated, says Northeastern finance professor Paul Chiou. But the costs of other items such as food and real estate may remain elevated. Photo by Alyssa Stone/Northeastern University

Sticker shock is real. Even hot dogs are way up. What’s going on here?

The increase in prices is determined by the invisible hands in an economy—demand and supply. The increase in prices varies from sector to sector and from goods to goods. Hot dogs can be one of the examples. What policymakers care about is the overall price level, such as the consumer price index (CPI).

There are several factors that we may want to pay attention to—the slower restart of domestic production lines in the U.S. and the restructuring of the global supply chain, which is causing a recent surge in shipping costs. Domestic production lines are still below the pre-pandemic level due to the shortage of imported materials and rising labor costs.

There is also higher demand for certain products such as cars, real estate, and food, that contribute to inflation.

To what degree did stimulus funds earlier this year contribute to a 13-year high in the Consumer Price Index?

Since the start of the pandemic, total Fed spending is roughly $3 trillion since April 2020. That includes loans and stimulus checks to individuals. Consider that total GDP [Gross Domestic Product] in the United States is about $21 trillion in 2020, which is about a loss of 5 percent due to the pandemic, fiscal policies actually injected a net 10 percent of GDP in the U.S. economy.

Federal funding helps maintain the liquidity of businesses and people and keeps them above water, but more money was invested by the federal government than the loss of GDP caused by the pandemic. Thus, the impact of the stimulus programs on inflation cannot be ignored.

Who benefits and who hurts from inflation?

The biggest winners of high inflation are borrowers and asset owners. They include the U.S. Treasury—the number one borrower in the world—investors in equities and real estate, as well as homeowners with mortgages. On the other hand, higher inflation hurts cash-savers, retirees, and workers with fixed wages. Companies with strong pricing power can benefit as the prices of their products and services can adjust rapidly with little concern about decrease in demand. Conversely, businesses whose customers are especially sensitive to prices, like restaurants and food manufacturers, hurt more and usually respond to inflation by shrinking their products, like making smaller hamburgers without lowering prices.

When do you think prices will return to Earth?

If you ask me the exact time, the question is above my pay grade. But overall, the answer depends on assets. The prices of some products, like used cars, possibly will decrease when the shortage of microchips and/or the shock of the Hertz bankruptcy relax. But due to the increase in the cost of materials and labor, real estate and food are unlikely to drop.

And remember that prices in certain sectors, like healthcare, have never stopped rising any time in the past two decades. We probably will live in a world of elevated inflation.

If the central bank doesn’t take its foot off the accelerator gradually now—and keep interest rates low—do you think it will have to slam on the brakes later with higher rates?

Like most developed countries, the central bankers in the U.S. always pay close attention to the balance sheet of the Federal Reserve to ensure the stability of the financial system. The last time the Fed raised rates to control inflation was in the early 1980s when Paul Volcker was chairman. The Fed aggressively increased interest rates by about 9 percentage points in about two years, leading to a recession with a 10 percent national unemployment rate.

Currently, as financial and housing markets are much bigger and sensitive to interest rate hikes, it is questionable for the Fed to raise rates rapidly and significantly again. The economic picture is very different today than 40 years ago. Inflation then was much higher due to the energy crisis and the federal government borrowed less—35 percent of GDP in 1980 vs. 130 percent in 2021.

As we learned from past quantitative easings to respond to the Great Recession of 2008, the Fed will gradually begin tightening monetary policy and shrink its balance sheet. But if we read between the lines of Powell’s July testimony, the Fed may not act until the labor market has strengthened further.

What are some of the economic outcomes in the United States if the virus rages back?

The world economy will of course be negatively affected again but would not be at the same degree as it was at the outbreak of the pandemic in 2020. Most investors realize that we may need to live with the COVID-19 virus forever, and have developed the knowledge and resources, like vaccines, telework skills, and so on, to respond.

Given the high vaccination rate in the U.S., the impact of the next pandemic wave on domestic economic activities will be diminished. But for industries related to international travel, like airlines and cruise ships, the impact may be significant.

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.