How afraid of COVID-19 variants should we be?

More than four million.

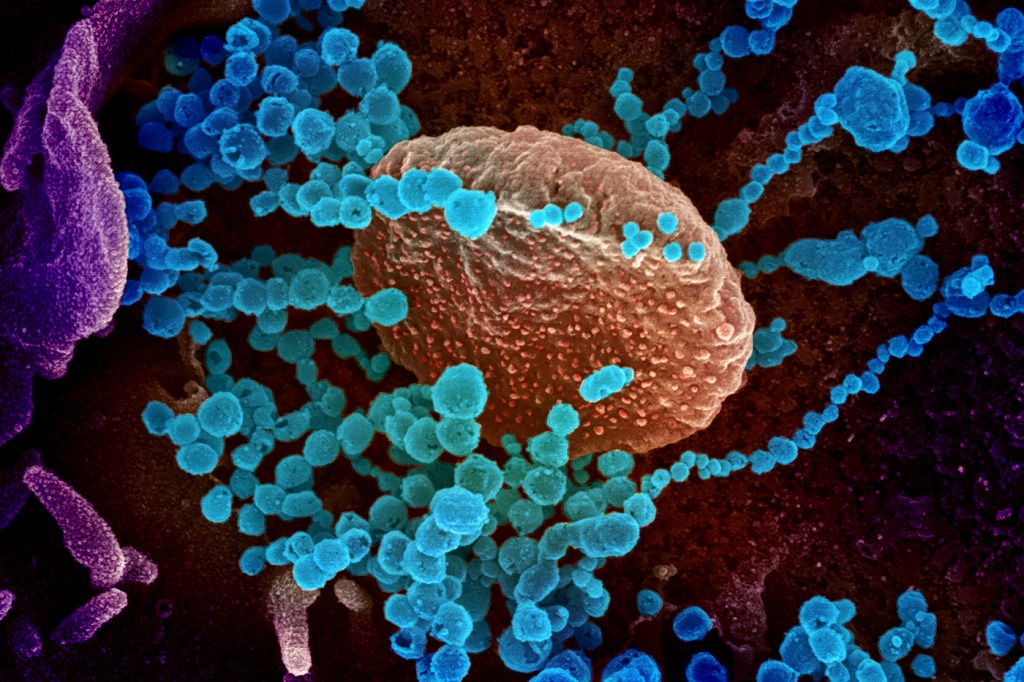

That’s how many people have been killed by COVID-19 globally as of Thursday. At least, that’s the officially reported number. As SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, continues to spread, it is mutating. It is those new strains of the virus that are largely driving the latest surges in unvaccinated populations around the world.

As dangerous variants of the virus emerge, public health officials are increasingly concerned about the capacity of the virus to mutate into versions that fully vaccinated people might not be protected from. Vaccines are still providing high levels of protection against the known variants, and are particularly good at preventing severe illness in fully vaccinated people—the vaccines’ infection-blocking mechanism has remained effective, for now.

Left to right: Mansoor Amiji, university distinguished professor and chair of the department of pharmaceutical sciences; Brandon Dionne, assistant clinical professor in the department of pharmacy and health sciences; and Neil Maniar, professor of public health practice and associate chair of the Department of Health Sciences and director of the Master of Public Health program, all in the Bouvé College of Health Sciences at Northeastern. Photos by Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University

“The worst case scenario is that a variant develops that can escape the protection from the vaccine,” says Brandon Dionne, assistant clinical professor of pharmacy and health systems sciences at Northeastern. “That’s what we’re really worried about.”

That’s already happening to some extent—although not to a concerning level yet, Dionne says. There have been more breakthrough cases of COVID-19 reported in fully vaccinated people since the Delta variant has been circulating than when earlier versions of the virus were dominant.

Still, Dionne says, the risk of variants adds to the sense of urgency around vaccination efforts, particularly in communities and countries where vaccination rates are low.

A higher level of vaccination rates could tamp down on the emergence of variants because of the conditions that a virus needs to thrive and mutate, explains Mansoor Amiji university distinguished professor of pharmaceutical sciences and chemical engineering at Northeastern. A virus survives by replicating itself, and a “virus in itself is not able to replicate,” he says. “It needs a host cell to replicate. And if you give a cell to this virus, it will figure out a way to make copies of itself.” And as it makes copies, it can make mistakes. Some of those changes can yield more dangerous variations of the virus.

If an infected person is surrounded by people who are immune, then the virus can’t find more hosts to continue that process, Dionne says. “The larger the pool of people who can become infected, the more likely we are to see mutations and then see new variants develop,” he says. “And then eventually one of those variants could evade the immune response from the vaccine.”

That usually doesn’t happen overnight, however. Rather, Amiji says, these mutations are usually very small. “And, in some ways, that’s good news for us.”

“Think about how the virus infects. The coronavirus enters through the nose and then it basically tries to find its receptor on the various surfaces of cells that are part of our upper respiratory tract. The virus binds to that receptor through the spike protein part of the virus. This is the mode of which the virus can access the cell,” Amiji says. “It’s almost like a lock and key mechanism. The virus finds that particular lock and it has that key in the spike protein, and it’s able to engage.”

Vaccines train the immune system to identify the coronavirus spike protein and block that lock-and-key match from happening. The fully vaccinated immune system can create antibodies that bind to the spike protein of the virus and neutralize it to prevent it from entering the cell. And, Amiji says, the vaccines code for the entire protein, so when one or two amino acids in the protein change when the virus replicates and mutates, the antibodies are still largely able to recognize and attack the virus. “Now, if the virus changes the entirety of this protein, then these vaccines will not be effective anymore,” he says. “But that hasn’t happened yet.”

So why, then, are we seeing more breakthrough cases with new variants (like Delta) but public health officials are saying the vaccines are still quite effective?

These small mutations can allow some viral particles to sneak past the antibodies undetected, Amiji says. So the concern is that as more and more of these mutations accumulate in the spike proteins, the antibodies will have a harder and harder time identifying them.

That’s what causing breakthrough cases in fully vaccinated individuals. But those breakthrough cases tend to be a lot less severe, even with the Delta variant, and generally fully vaccinated people who contract it are asymptomatic or essentially have a cold, says Neil Maniar professor of public health practice and associate chair of the Department of Health Sciences and director of the Master of Public Health program at Northeastern. “I think that’s pretty effective.”

But that’s not a reason to sit back on our laurels if we’re vaccinated, Maniar says. “The Delta variant has shown what this virus can do. And viruses are going to continue to mutate. And they will mutate to their advantage, not to our advantage.”

The Delta variant also seems to be the most transmissible and infectious version of SARS-CoV-2 to spread around the world yet. It now accounts for more than half of all new infections in the U.S., if not more, and is the dominant strain globally.

As the coronavirus has shown time and time again, the disease and its variations spread globally quickly. “Viruses, like the coronavirus, don’t require a passport or a visa to go to different parts of the world,” Amiji says, so vaccination efforts must take a global approach. “When this infection remains in any part of the world, no one is ever going to be 100 percent safe in any part of the world.”

Still, he says, “It’s not about being scared. But it is still with us, and we have to be vigilant.”

For media inquiries, please contact Jessica Hair at j.hair@northeastern.edu or 617-373-5718.