The myths and the realities of mass shootings in the US today

In the United States, mass shootings have never garnered as much attention as they have over the last decade. From the massacre at Sandy Hook Elementary in 2012 to the Atlanta spa shootings this past March, incidents of gun violence involving multiple casualties are now accompanied by endless media coverage and analysis, suggesting that such violence is occurring more frequently than ever before.

But are mass shootings involving four or more fatalities on the rise in America?

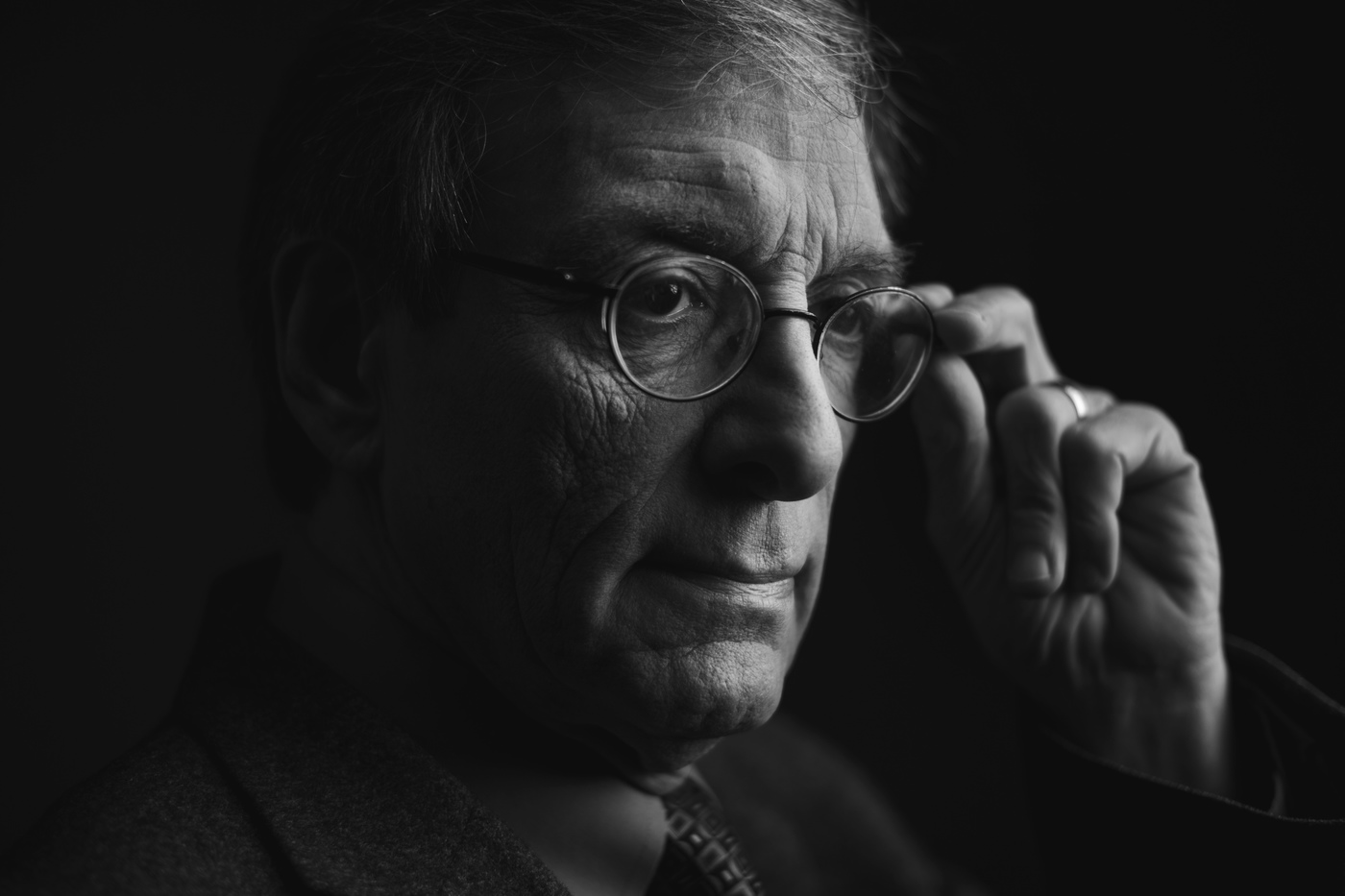

James Alan Fox, the Lipman Family Professor of Criminology, Law, and Public Policy at Northeastern. Photo by Adam Glanzman/Northeastern University

James Alan Fox, a criminologist at Northeastern University and an international expert on mass murder, says there’s been little change in frequency over the last few decades, with about two dozen occurring per year on average.

Polling and survey data shows that people in the U.S. are increasingly fearful of mass shootings—a perception that Fox, through his research and writings, has been trying to counter for years. Three-quarters of U.S. adults in one recent survey, for example, said they are stressed out by mass shootings, with one-third saying their fear of such shootings causes them to avoid certain public places and events. Another survey found that nearly half of U.S. residents fear being the victim of a mass shooting.

This widespread fear has far outgrown the actual threat posed by public mass killings, Fox says. While these public killings are, by their very nature, terrifying—particularly when they involve the indiscriminate slaughter of people in places like supermarkets, movie theaters, concerts or restaurants—they are still quite rare, Fox says.

“There’s no epidemic of mass shootings in my mind,” Fox says. “Really there is an epidemic of fear.”

The problem, he says, is the confusion generated over “mass shootings,” which may not involve fatalities, with “mass killings,” where there are deaths, but not necessarily by guns. In the wake of a deadly shooting with four or more deaths, reporters have sometimes cited statistics on mass shootings, of which there are typically hundreds per year; but only one person dies on average during a mass shooting, and nearly half are family massacres in private homes, Fox says.

“Another significant share are gang-related shootings, drug-related, or armed robberies,” Fox says. “Very few are the random indiscriminate public slaughters that everyone is afraid of.”

Criminal Justice professor Jack McDevitt. Photo by Adam Glanzman/Northeastern University

For example, there were 610 mass shootings in 2020—and 21 “mass murders”—but only 20 percent occurred in public settings, according to Fox. And as it relates to mass killings, which are tracked by the AP/USATODAY/Northeastern University Mass Killing database, about one-quarter don’t even involve guns, Fox says.

But researchers at Northeastern have been tracking a trend in mass shooting events that lends itself to this discussion—that is, the use of guns in hate crimes. Historically, fewer than 1 percent of hate crimes are committed with guns, but that appears to be changing, according to Jack McDevitt, who directs the Institute on Race and Justice at Northeastern.

“There have been a series of shooting incidents lately that are bias-motivated,” McDevitt says.

And a number of these mass murders where McDevitt says hate could be a strong motivator have been among the deadliest in recent memory. In 2016, a shooting at the Pulse nightclub—considered a haven for the LGBTQA community—in Orlando, Fla. left 49 people dead and another 53 injured.

Earlier this year, a shooting spree in several Atlanta spas left eight dead, six of whom were Asian. The Pittsburgh synagogue shooting involving the killing of 11 Jewish congregants in 2018, and the Charleston church massacre in 2015 in which a shooter killed nine Black churchgoers, are two more examples of incidents linked to hate, McDevitt says.

Like Fox, whose research informs the AP/USATODAY/Northeastern database on mass killings, McDevitt has long worked to improve the reporting and investigating of hate crimes, authoring a report in 1998 on the subject that was soon after adopted by the U.S. Justice Department.

But the long-term data on how hate and bigotry inform gun violence is still sparse, McDevitt says.

“It could be a turning point in hate crimes if we start to see offenders arming themselves with guns,” McDevitt says. “In the area of hate crimes, guns were seldom a weapon of choice.”

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.