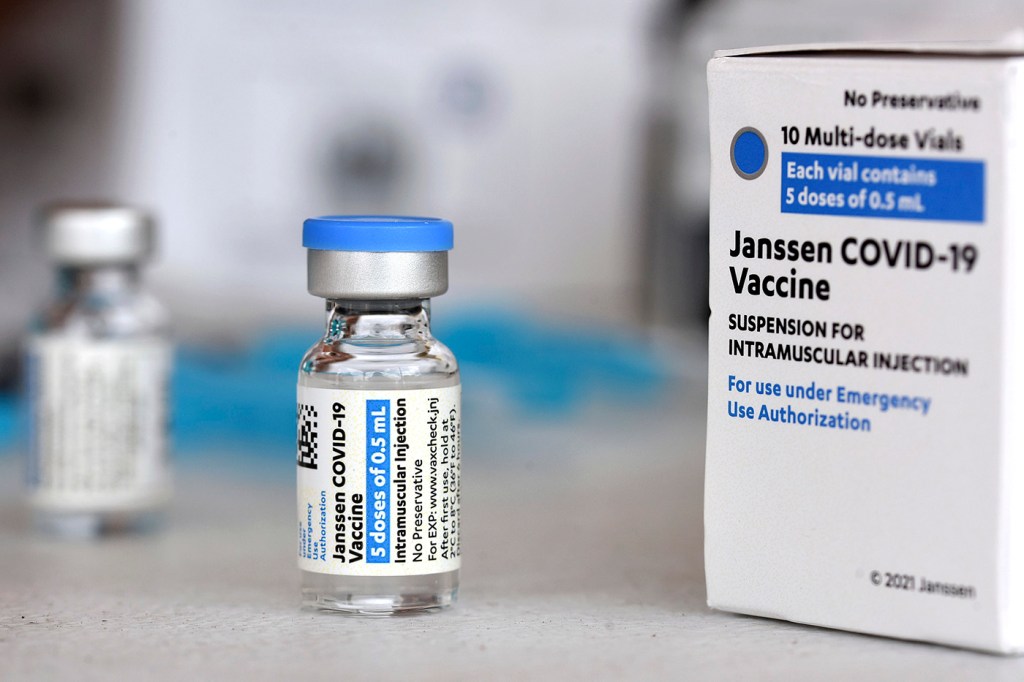

With the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine pause, getting the message right is critical

As the distribution of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine remains on hold while federal health officials review a potential blood-clotting side effect, public health authorities and scientists find themselves in a delicate position when it comes to the messaging about the safety and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines to the United States public, two Northeastern scholars of public health law and communications say.

Last week, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Food and Drug Administration said they were reviewing reports of six cases in which women who received the single-shot vaccine developed a rare, dangerous blood-clotting disorder. It’s not clear yet whether the vaccine is related to or caused the health condition, and the CDC recommended pausing its distribution “to be extra careful,” according to the announcement.

Left, Susan Mello is an assistant professor of communication studies. Right, Wendy Parmet, Matthews distinguished university professor of law and director of the Center for Health Policy and Law at Northeastern. Northeastern file photo.

Public health officials and Northeastern researchers Wendy Parmet and Susan Mello are concerned that the pause, if it’s not communicated clearly, might be the tipping point for members of the public who were already hesitant about getting a COVID-19 vaccine to decide not to get inoculated against the highly contagious disease.

“I think regulators have to thread a very fine needle, and they’re doing so in a moment that is very fraught,” says Parmet, Matthews distinguished university professor of law and director of the Center for Health Policy and Law at Northeastern.

“We have a pandemic that is still very much raging in some parts of the country, we have a very active anti-vaccination movement and a significant percentage of the population outside of the movement who are hesitant of vaccines in the first place,” she says. “We’re in a pickle here.”

Such an effect could have widespread consequences as the U.S. races to vaccinate enough of the population to reach herd immunity—the threshold at which enough people are immune to a disease to suppress its spread and protect more vulnerable populations.

“This is exactly what you didn’t want to happen, in terms of potential side effects,” says Mello, assistant professor of communication studies whose research includes risk perception and health communication.

But, she says, there are early indications that public health officials are successfully navigating this communications quagmire.

Mello says that both health authorities and journalists are stressing the rarity of the blood clots—6.8 million doses of the vaccine have been administered and only six cases of clotting have occurred, making the odds more than one in a million.

“People will often think of themselves as that one, though,” Mello says, which is why it’s also important that officials stress the relative risk.

The odds are significantly higher that people who use oral contraceptives will develop similar blood clots, “and people have been taking birth control for years,” Mello says. And the odds of developing blood clots after being hospitalized for COVID-19 are roughly one in five.

“What we’re seeing is that you’re much more likely to contract COVID-19, and then much more likely to experience blood clotting from the disease than you ever are from getting the vaccine,” Mello says.

Anthony Fauci, considered among the top infectious disease doctors in the U.S., expects Johnson & Johnson to get its vaccine “back on track” shortly, after which it would become available to the public once again, although perhaps to a more specific portion of the population, if the instances of blood clotting in young women is associated with the vaccine.

Because it’s likely to be back, Mello says the use of the word “pause,” instead of something more finite, was a good choice.

After all, Parmet says, public opinion on matters related to health aren’t as crystalized as they may have become on other social and political issues.

“There’s a significant portion of the population who may have inclinations and questions, but what studies have shown is that people can change their minds over the course of engagement with medical information provided by their doctors,” she says.

“The stakes are high right now,” Parmet says. “We want a vaccine that is safe and we want to save lives, but we don’t want to give a vaccine to subpopulations that may be particularly vulnerable to it if we have other choices for them.”

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.