Why Trump-era immigration rule likely is impacting Hispanic inoculations

A “stigmatizing” Trump administration immigration rule that determined health benefits for green-card applicants and others is not being enforced by the Biden administration. But lingering fear of it may be hampering vaccination rates among immigrants.

“It is incredibly stigmatizing and was designed to create fear,” professor Wendy Parmet says of the so-called “public charge rule,” created in 2019 but since vacated by President Joe Biden’s administration. It “was not in keeping with our nation’s values,” Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas said in a statement.

U.S. vaccination records are not kept according to a person’s immigration status, explains Parmet, the Matthews distinguished university professor of law and director of the Center for Health Policy and Law. “There’s good reason for that—immigration fears can deter people from getting vaccinated,” she says.

“Immigration fears can deter people from getting vaccinated,” says Wendy Parmet, Matthews distinguished university professor of law. Northeastern University file photo

Congress should consider removing the public-charge provision entirely from the larger Immigration Act, which dates back to 1882, as one avenue to remove some of the deep-rooted unease, Parmet recommends. The government also should mount a public-relations campaign through community groups to let immigrants know it isn’t enforcing the rule.

Obtaining concrete vaccination data will be complicated, she adds. “To what extent fear of the public-charge rule and immigration is thwarting vaccinations is hard because people are very afraid to talk about these things.”

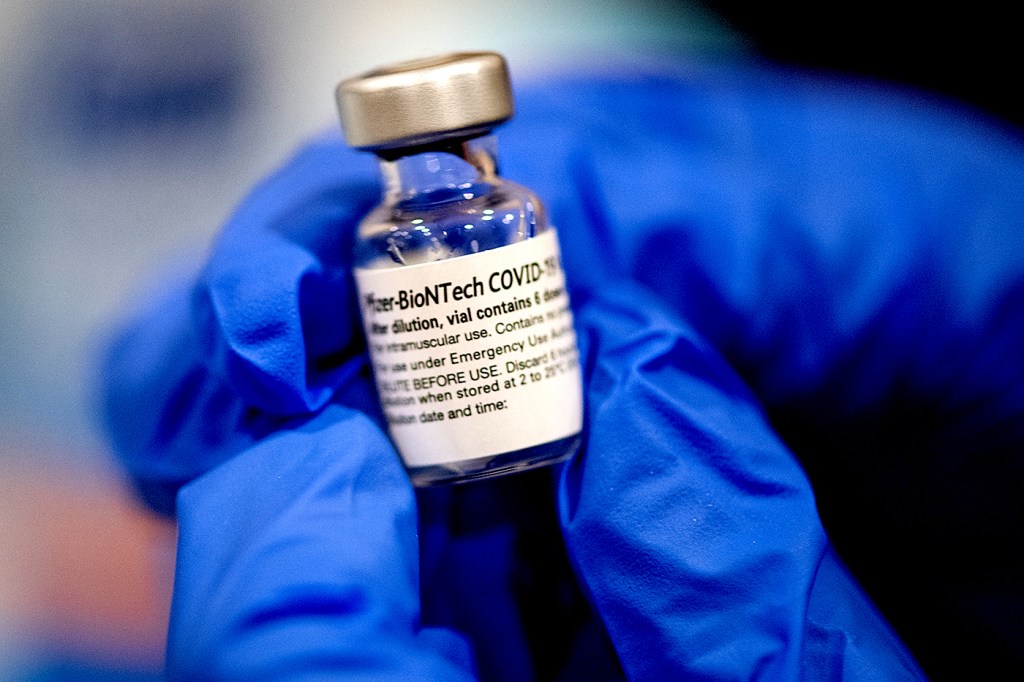

Empirical data reveal Hispanics have the lowest vaccination rates compared to other racial groups, according to a March study by Northeastern, Harvard, Northwestern, and Rutgers. They also register higher levels of hesitancy and lower levels of access to vaccines, researchers found.

The national survey did not ask respondents why they were reluctant to get inoculated or their immigration status.

Parmet suggests that trepidation over submitting a name into a database to get a perceived “government” vaccination shot may be contributing to the low numbers. Another reason may be that the threat posed by the public-charge rule hasn’t completely gone away.

Republican attorneys general from a handful of states, including Arizona, sued the White House to defend the rule. The suit is pending before the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals located in San Francisco, the largest of the 13 courts of appeals. Ten of the 29 judges on the Ninth Circuit were appointed by former President Donald Trump.

Under the original public-charge rule, immigrants who were “unable to take care of himself or herself without becoming a public charge” could be denied visas or permission to enter the United States. The Immigration Act of 1903 expanded the scope of the rule, allowing the federal government to deport immigrants who become a public charge within their first two years in the country.

The Trump administration broadened it further in 2019, defining “public charges” as immigrants who received government benefits such as Social Security or public housing, and authorizing immigration officials to investigate green-card applicants regarding their financial status.

The measure doesn’t affect refugees or asylum-seekers, but does apply to many other non-citizens in the United States who wish to change their status. They include people such as individuals on work visas who marry U.S. citizens.

The rule created a deportation risk for people who were eligible for benefits. And it effectively created a de facto point-based immigration system for low-income people who lacked benefits such as health insurance, Parmet says.

Now that the Biden administration has moved on from it, the rule still casts a long shadow. Parmet says there also is concern about what happens with the next presidential election in 2024. “People may wonder ‘If I use a benefit now, is it going to come back and bite me? What if Trump comes back?’”

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.