As feared, hate crimes targeting Asian Americans rose sharply during the COVID-19 pandemic

Asian Americans are increasingly being targeted in hate crimes as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic—a deplorable wave that was anticipated by Jack McDevitt, director of the Institute on Race and Justice at Northeastern.

“It’s very serious, and we knew it was coming,” says McDevitt, a professor of the practice in criminology and criminal justice who has been studying hate crimes since the 1980s. His institute received a grant from the state of Massachusetts last year to create a hate-crime guide for schools in Massachusetts that was based in part on “fear that unjust blame for the pandemic would be suffered by people who are perceived to be Asian American.”

The attackers have cut across a wide swath of the Asian American community, says Carlos Cuevas, a professor of criminology and criminal justice who co-directs the Violence and Justice Research Lab at Northeastern.

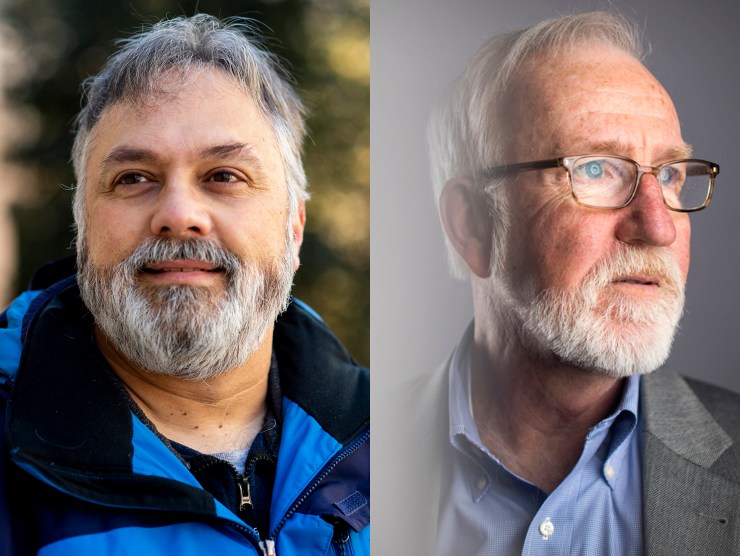

Left, Carlos Cuevas, a professor of criminology and criminal justice who co-directs the Violence and Justice Research Lab. Photo by Ruby Wallau/Northeastern University. Right, Jack McDevitt, director of the Institute on Race and Justice. Photo by Adam Glanzman/Northeastern University.

“You have to think about people who perpetrate hate crime or bias-driven violence,” Cuevas says. “They are not having a full-blown intellectual evaluation about what they’re going to do. They have heard the messages around China as the cause of the virus, and then they target somebody because they perceive that person to be from that place.

“They’re not going to ask, ‘Are you from China? Are you from Japan or Korea?’ They’re not going to care. They’re going to perceive you as the group that they are focused on. And they’re going to target those individuals.”

U.S. hate crimes have been rising overall since 2016, after a decade in which they had been waning. The FBI recorded 7,314 hate crime incidents in 2019.

There were 122 such incidents in 2020 that were directed at Asian Americans in 16 major U.S. cities, according to California State University’s Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism. That represents a 150 percent increase, which has led Brian Levin, executive director of the hate and extremism research center, to predict that “2020 will be the worst year this century for anti-Asian hate crime.”

The number of reported hate crimes amounts to “the tip of the iceberg,” says Cuevas, who notes that the FBI’s definition of a hate crime doesn’t account for acts of harassment or slurs that are viewed as protected free speech.

McDevitt says hate crimes are “vastly underreported” for several reasons: Victims don’t trust the police, they’ve been threatened by offenders to not report the crime, or they believe that nothing will change.

The U.S. has a history of anti-Asian American activity, including the establishment of Japanese internment camps during World War II. The recent trend of anti-Asian American hate crimes has been fueled by political rhetoric during the pandemic, including labeling of COVID-19 as the “Chinese virus” or “Kung-flu.”

McDevitt says hate against Asian Americans has been registered in online chat rooms. Further amplifying the rage is China’s ascension as a world power and rival to the U.S. in the form of trade and culture wars. Altogether it reminds him of the assaults suffered by people who were perceived to be of Arab descent after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001.

“The largest increase in hate crimes against a particular group was against people perceived to be Arab American after 9/11—there was a huge spike in hate crimes that year,” McDevitt says. “What we’ve seen is that some people feel defensive against a group because they perceive that group to have done something to them. We’re seeing the same thing here, partly because of the rhetoric around it being a Chinese disease, and the sheer volume of misery that COVID-19 has caused. There are a number of people out there who are blaming people they perceive to be Asian, and trying to retaliate against them, for bringing COVID-19 to the United States.

“It’s all wrong. These people weren’t involved. But that’s the way it goes in the rhetoric put forth by organized hate groups over the internet.”

Cuevas hopes that U.S. political leaders will seek to reduce tensions.

“The tone and rhetoric of leadership does matter,” says Cuevas, who ran a National Institute of Justice-funded study of bias victimization among Latino adults in the U.S. “Shifting the blame game is one thing. Another thing that’s really important is trying to educate people about the makeup of this country and what this country is going to look like” as the U.S. continues to diversify.

Based on interviews with hate-crime victims over the years, McDevitt has learned of their needs in three areas.

“They want leaders in the community—it could be a college president, a mayor, a governor, or a CEO of a company—to stand up and publicly denounce the attack,” McDevitt says. “The offenders think that everybody else shares their biases, and that they’re the only ones who are brave enough to act on it: They see themselves as heroes. And we have to confront that and say, ‘no, what happened here is wrong.’

“The second thing is that the police have to take it seriously,” says McDevitt. “One of the reasons for that is because of the commonplace threat from offenders that if you go to the police, we’ll come back and get you or your family. There’s no group in our society that can offer protection other than the police. Consequently, the police have to prioritize protecting the victim.

“And then the third thing that they say is most important to them is for their neighbors, co-workers, and members of the community to step forward and say, ‘We want you to be part of our community,’” McDevitt says. “That makes the victims feel like everybody doesn’t hate them, that there are people who are their allies. Because you wonder, if you’re the victim, does everybody share the bias of the offender? It’s really important that we as members of the community step forward and share with the victims that they are an important part of the community and we value them.”

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.