Will more states follow California’s lead in adopting new COVID-19 lockdown measures?

In the wake of a post-Thanksgiving surge in COVID-19 cases, more states will need to follow California’s lead in adopting restrictive mandates, says a Northeastern professor who has closely tracked the virus over the course of the pandemic.

Samuel Scarpino, an assistant professor in Northeastern’s Network Science Institute, warns that inaction on the surging pandemic will lead to tragic consequences—and thus, far-reaching lockdowns will be necessary to bring the surging pandemic under control in the coming months.

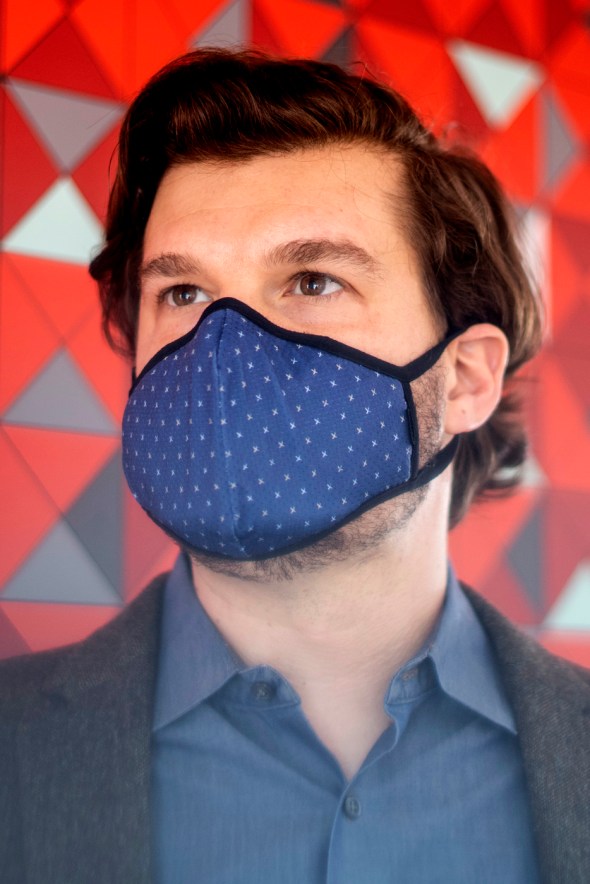

Samuel Scarpino, assistant professor in Northeastern’s Network Science Institute. Photo by Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University

But he says states and the federal government will need to provide better messaging and support to help people make it through a second shutdown.

California’s restrictions, which include a ban on indoor and outdoor dining, and closure of recreational facilities and hair salons and barbershops, were enacted Dec. 5 as burgeoning cases threatened to overwhelm hospitals in the country’s most populous state. The restrictions resemble those established in March when California was one of the first states to enact strict measures to combat the coronavirus outbreak.

“Most places in the United States are past the point where anything besides a lockdown is going to be effective,” says Scarpino, who heads the Emergent Epidemics Lab at Northeastern. “Lockdowns have to go into place to save lives.”

But those measures might be met with more resistance from the public this time around. Rising cases have tended to coincide with an increase in “pandemic fatigue.” With no end in sight, people are less motivated about following recommended public health measures to protect themselves and others from the virus. They’re frequenting bars again, attending family parties, and returning to offices and classrooms—all while skipping masking and social distancing protocols.

That’s why this time, public officials will need to do more to enforce compliance with the regulations. A top-down approach won’t work again, says Scarpino. What has proven effective is educating the public and providing them with the resources they’ll need to comply—a federal stimulus, for example, would allow some people to stay home from work, he says.

Congress is currently debating a $908 billion measure to provide an economic lifeline to small businesses and the unemployed, but no deal has been struck yet. Lawmakers are racing to finish before adjourning later this month.

Communicating a plan and timeline to the public about how states will distribute a COVID-19 vaccine and steps to returning to some semblance of normal life could also reinvigorate public vigilance, says Scarpino.

“One of the things that we’ve continued to lack in this country is a plan that says: Here’s what we’re asking you to do. Here’s why we’re asking you to do it. Here’s when it ends, and this is what the end looks like,” he says.

Early on in the pandemic—and in the absence of strong federal leadership—states were left to improvise their own responses. This meant sweeping stay-at-home orders were instituted even in areas where cases were low or non-existent.

“In many places in the U.S. that locked down, it didn’t really do very much, and that’s part of what contributed to lockout fatigue,” Scarpino says.

Additionally, chronic underfunding of public health and underinvestment in public health data infrastructure resulted in a lack of effective COVID-19 data collection and disease surveillance systems, leaving many states flying blind.

“As a result, that means we don’t really know what’s working and what’s not working,” Scarpino says. “This leaves us with the unfortunate option of closing everything down or leaving everything open.”

Still, Scarpino emphasizes the importance of early intervention to curb the spread of an infectious disease, and notes that the lockdown measures established in March “very clearly” saved lives. Studies published later showed a faster response could have saved thousands more lives, he says.

“Again, that goes to this idea that acting early is better, even if whatever you do doesn’t work as well,” he says.

Conversely, states such as Massachusetts, which introduced restrictive lockdown restrictions early but then lifted them prematurely, fueled a resurgence of coronavirus cases, says Scarpino.

The lack of a cohesive national plan that includes bailout and stimulus money is once again forcing states into impossible situations, he adds. Draconian shutdown restrictions, such as the ones adopted by California, will inevitably have significant consequences on the economy and on people’s lives.

“We’re kind of forced into this impossible situation of either letting COVID-19 run rampant—as we’re doing in Massachusetts—or shutting everything down and taking the huge economic consequences, as they’re doing in California,” he says.

The coming weeks and months are going to be critical to controlling this latest surge as the holidays approach and the promise of a vaccine looms, Scarpino says.

“Every day that we delay [a shutdown] just pushes that back further,” he says.

For media inquiries, please contact Marirose Sartoretto at m.sartoretto@northeastern.edu or 617-373-5718.