Researchers observe the bizarre sexual behavior of shipworms for the first time

One afternoon, a researcher walked into his lab at Northeastern’s Marine Science Center and saw something shocking: A competitive sexual frenzy was happening right before his eyes, with individuals wrestling and sparring for dominance. The participants? A cluster of shipworms—marking the first time this unusual sexual behavior has been observed and documented.

Shipworms are fleshy, worm-like mollusks that use their shells to carve into unprotected logs, driftwood, docks, and ships and make themselves at home. Once burrowed, the wood-eating clams stay put, slowly eating through their own habitats (and causing billions of dollars of damage to wooden structures in the oceans).

Shipworms have two snorkel-like siphons that are used to bring water in and expel waste. These siphons are the only part of the clam that protrudes from its wooden home.

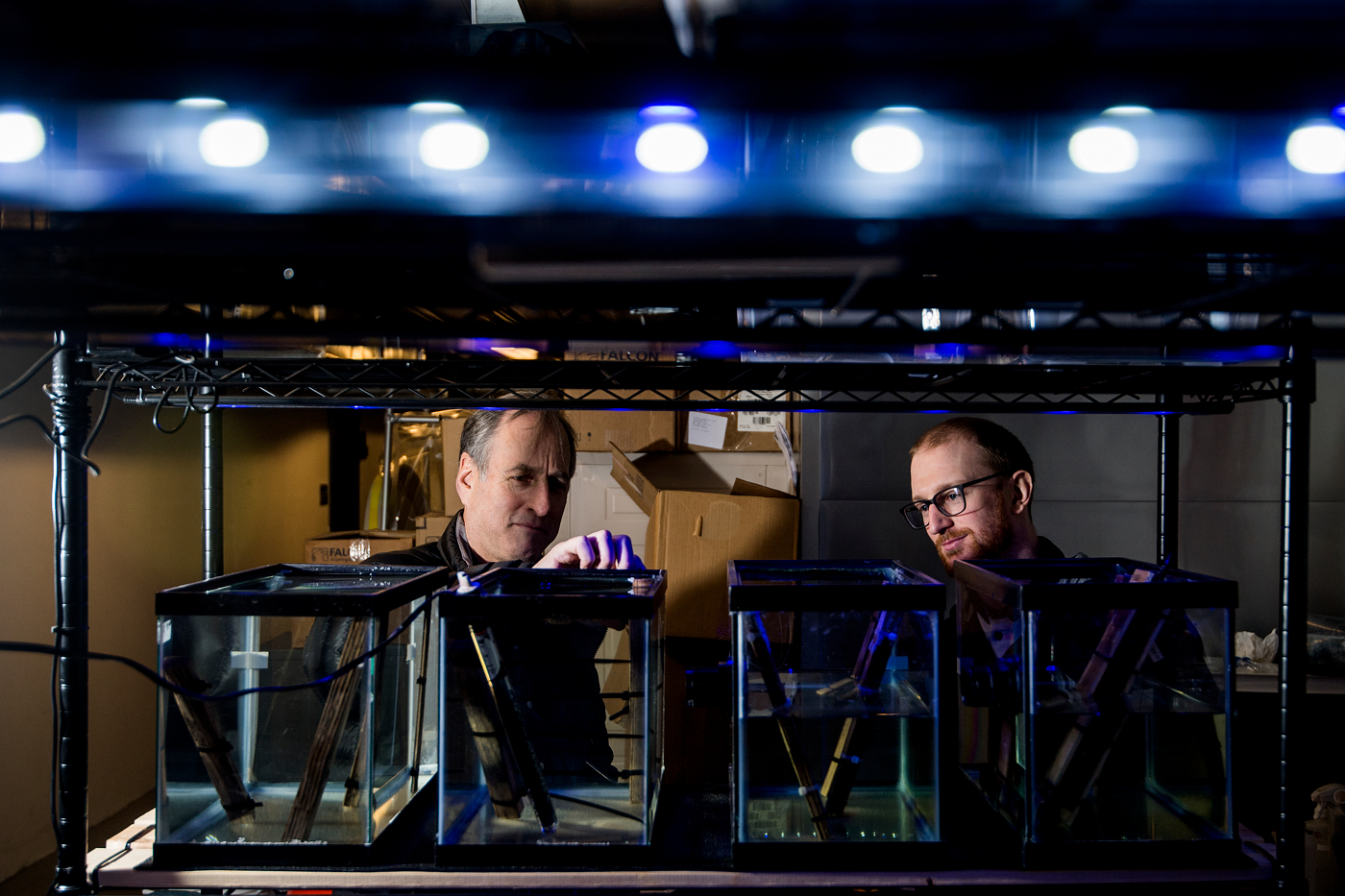

Dan Distel and Rueben Shipway are renowned researchers of shipworms. They discovered a new genus of shipworm in the Philippines in 2019. Photo by Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University

But, as it turns out, that’s not all those siphons are good for.

“This type of mating—where one animal puts its siphon inside another animal’s siphon and releases sperm—is basically unknown in bivalves,” says Dan Distel, who directs the Ocean Genome Legacy Center at Northeastern’s Marine Science Center.

Bivalves (a class of animals that includes mollusks with a hinged shell, such as clams, mussels, scallops, and shipworms) utilize a variety of techniques to mate with each other, says Distel, who co-authored a new paper about the rare sexual behavior of the specific shipworm known as B. setacea.

Most bivalves expel eggs and sperm into the water around them and hope for the best. But shipworms display an unusually complex variety of strategies to increase the likelihood of reproductive success. For example, some shipworms nurture their young in a protective brood pouch before releasing them into the wild. In others, the female maintains a harem of up to 100 tiny dwarf males in a special pouch, where they’re ready to provide sperm for her fertilization.

But the behavior witnessed in the lab by Reuben Shipway, a researcher at the University of Portsmouth who completed his post-doctoral research with Distel at the Ocean Genome Legacy Center, stands out even among such variety.

Distel, Shipway, and their colleague Nancy C. Treneman from the Oregon Institute of Marine Biology, studied 79 shipworms in a single piece of pine in an aquarium. Of those, 74 mated with each other while five remained on the sidelines, lodged in place in the wood and too far away to take part.

The researchers identified distinct stages of the mating behavior, which is known as pseudocopulation.

First, the intake, or incurrent siphon on a recipient mollusk becomes inactive and opens wide. (Shipworms are gender-fluid, and have been observed reproducing indiscriminately.) Then, the expelling, or excurrent siphon on a donor mollusk inches along the surface of the wood until it encounters the recipient siphon of a neighbor. Once they’ve found each other, the siphons entwine and the donor transfers the sperm to the recipient. Finally, fertilized eggs are released into the sea, where they’ll find their own wooden homes to burrow into.

Vying for an advantage, the shipworms use their siphons to wrestle and joust with each other in order to deposit sperm into another shipworm’s receptive siphon. Some of the mollusks the researchers studied received sperm in one siphon and planted their own sperm in a different shipworm at the same time, Distel says. Others were observed removing the sperm of a rival neighbor from a receptive shipworm in order to deposit their own. And shipworms that grow faster, and have longer siphons, can reach more distant neighbors for mating.

“It’s a rare and sophisticated form of reproductive behavior, with sparring between rival mates, pulling potential mates closer and away from rivals, and going as far as to include pulling a rival’s sperm out of a siphon so it floats away,” Shipway says.

Distel adds: “While pseudocopulation has been known for some time to occur in shipworms, this may be the first time the behavior has been caught on film and the first time its apparent competitive nature has been revealed.”

The findings, which were published in Biology Letters on Wednesday, help shed light on the distinct way that shipworms have evolved to survive, Distel says.

“When you’re stuck in a piece of wood, you can’t run out and find mates,” he says. There’s a ticking clock, too: Shipworms eat the wood they live in, destroying their own habitats as they go. Therefore, Distel says, “any strategy you can find to make mating more successful is going to help make the species more competitive.”

For media inquiries, please contact Shannon Nargi at s.nargi@northeastern.edu or 617-373-5718.