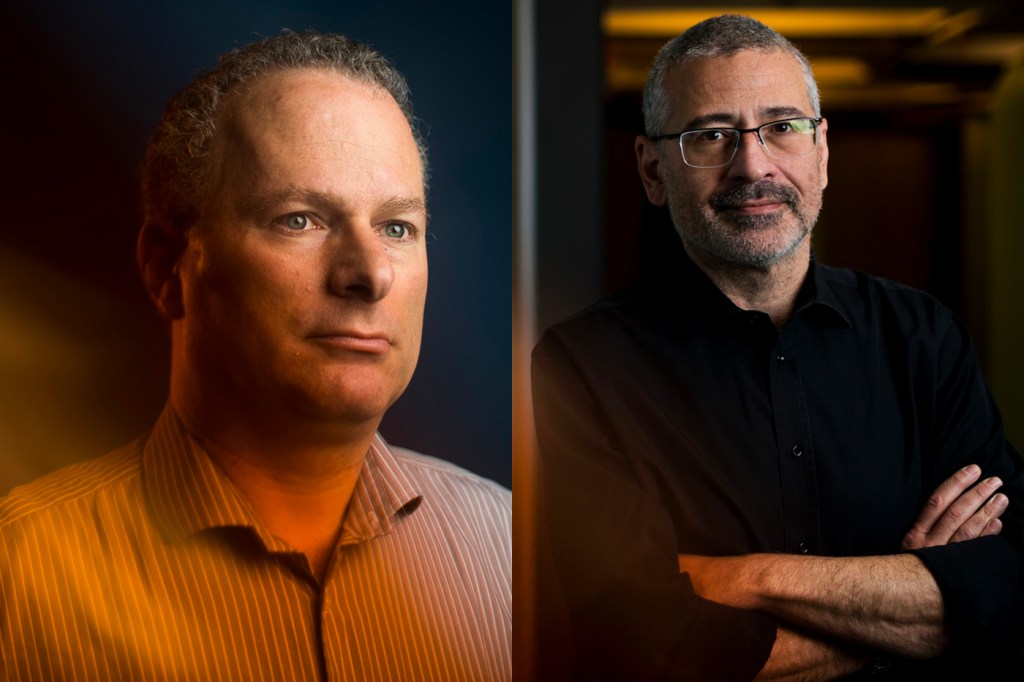

These professors are forecasting the COVID-19 pandemic and gauging public opinion about it

One night last February, on his way to a yoga class, professor David Lazer poked his head into the office of his colleague Alessandro Vespignani and asked a question about an emerging disease from Wuhan, China: “How bad is it, really?”

“I haven’t been to yoga or had a zen moment since,” says Lazer, the University Distinguished Professor of political science and computer and information science. “After that, I asked myself: ‘What can I do?’”

Since receiving that early warning about COVID-19 from Vespignani, the Sternberg Family Distinguished University Professor of physics, computer science, and health sciences, Lazer has conducted a series of nationwide surveys that gauge everything from the public’s support of a vaccine to people’s satisfaction with how the government has handled the crisis.

Lazer explained this project during a virtual panel on Thursday titled “Social Dimensions of the Pandemic.” He was joined by Vespignani and two other professors—Andrea Parker from Georgia Institute of Technology and Jacqueline Wernimont from Dartmouth College—to discuss their research and how it helps us better understand the spread of COVID-19.

Since starting his project this spring, Lazer has conducted 16 surveys that examine the health, economic, and political impacts of the pandemic.

“If I had to summarize the impacts in one word it would be ‘unequal,’” he says. “The metaphor I think of is an automobile accident. In the same accident, you could have some people fatally injured and others who walk away unhurt, and that’s the situation we’re finding ourselves in.”

The three main causes of these inequities are biology, sociology, and luck, Lazer says. Some people are at a higher risk for extreme complications due to COVID-19, for example, and others are more likely to contract the disease because of their living situations or work environments.

And then there are people who get stuck in the wrong place at the wrong time—such as those who attended unforeseen superspreader events at the beginning of the outbreak.

Lazer’s most recent survey focuses on bipartisan differences in intention to vote by mail as a result of the pandemic in the 2020 general election.

According to the results, more Democrats than Republicans are expected to vote by mail, which could mean that some states will “most likely have substantial vote shifts toward Biden that could affect the outcome of the election,” he says.

During the panel, Vespignani, who is also the director of the Network Science Institute, explained his research, which involves modeling and forecasting the pandemic using mobility data among other information about specific populations.

“We take advantage of all the data we have access to—flights, commuter patterns, age structures of a population,” he says.

For example, during the early stages of the pandemic, it was hard for researchers to access information about how many cases there were in China. But through the use of mobility data—how many flights go between China and Japan, and how many cases are now in Japan?—Vespignani and his team were able to work backwards.

“One of the other big questions we’re looking at now is once we have a vaccine, what do we do with it?” he says.

A recent study conducted by Vespignani and other researchers at Northeastern’s MOBS Lab found that if vaccines were allocated equally to each country based on population, 61 percent of deaths could be averted. Alternatively, only 33 percent of deaths would be averted if the vaccine were monopolized by wealthier countries that could afford to stockpile available doses.

The MOBS Lab is one of 44 organizations that inform the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s national COVID-19 deaths forecast.

“But unfortunately there’s no other similar operation at work internationally. Right now, it’s all a patchwork response,” he says. “This is one of the things I’m advocating for—we need to build an international forecasting system for outbreak science.”

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu