Working with Ruth: A law professor reflects upon his time as a colleague of Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s

In 1970, Michael Meltsner—who is currently the George J. and Kathleen Waters Matthews Distinguished Professor of Law at Northeastern—was hired by Columbia University to create a clinical program within its law school. While he was there, Meltsner worked alongside a cadre of lawyers who brought a new perspective to law. Among them: Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

The clinical law program Meltsner co-founded was one of the first of its kind, designed to give students a hands-on experience in representing underserved communities, he said, something that, at the time, was rather controversial.

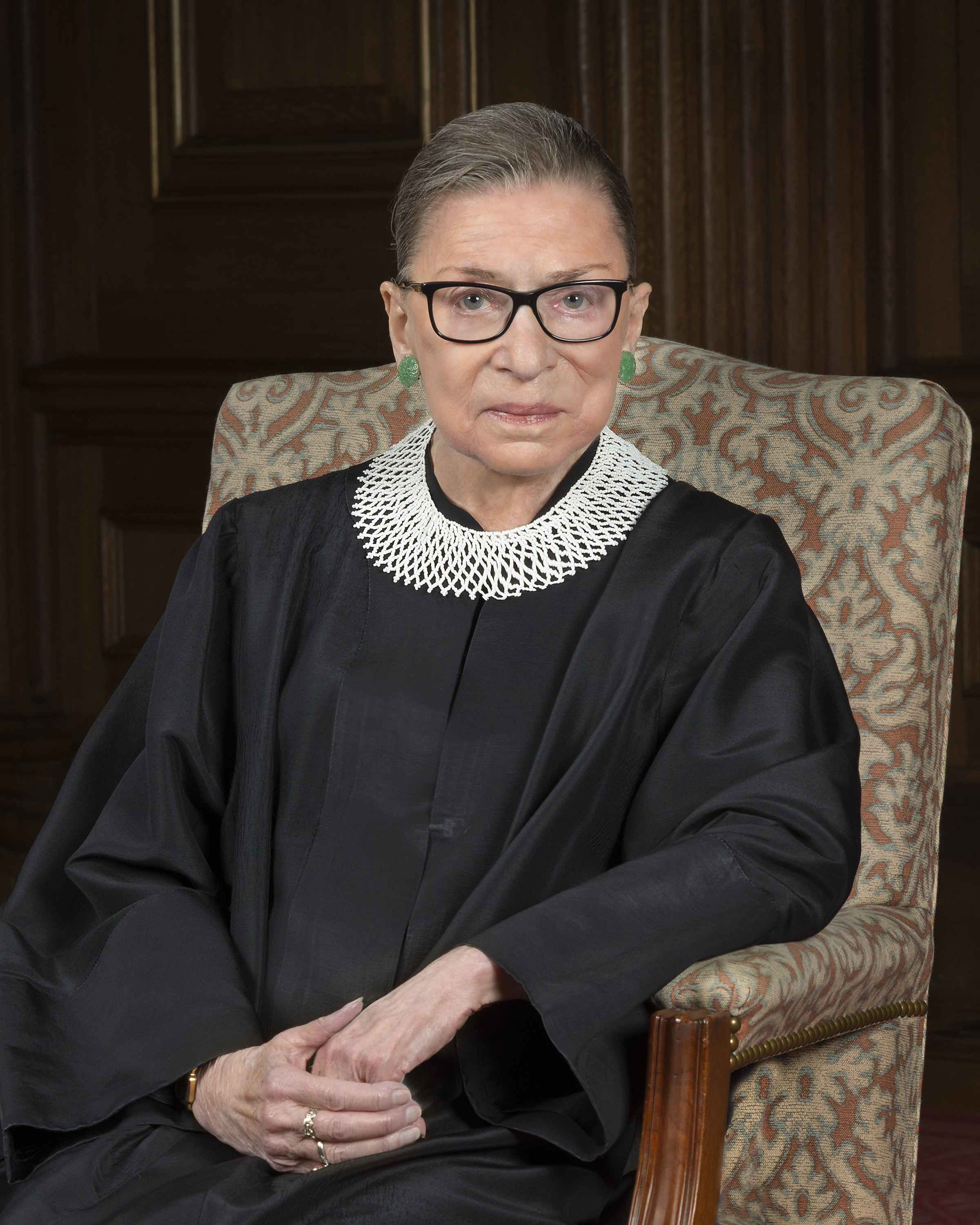

Official Photograph of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg from the Supreme Court of the United States

“Until around that time, American legal education was primarily cerebral and analytic,” Meltsner said.

To take on the project, Meltsner had left his position as first assistant counsel at the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) Legal Defense Fund.

At Columbia, there was a sense of outsider-ness among the group of law teachers hired to create a more experiential, real-world clinic that would shake up the heady legal education system.

Two years after his arrival, a young firecracker lawyer was hired to join the faculty in a move that many celebrated for its historic nature. According to reporting by The New York Times and Meltsner’s own recollection, Ginsburg was, in 1972, the first woman to be hired as a full-time professor in Columbia Law School’s then-114-year history.

Ginsburg made an “indelible” impression upon Meltsner from the very start, he said. One day, on his way to hand papers to his secretary, Meltsner knocked on Ginsburg’s door to welcome her.

In a post for the Human Rights at Home blog (co-edited by Northeastern’s own law professor Martha Davis), and an interview with News@Northeastern, Meltsner said Ginsburg was sitting “facing away from her desk, toward a dormitory building that blocked our full view of Morningside Park.

“She swiveled in her chair to greet me. Hair pulled back in a bun, crouched over a yellow legal pad, she acknowledged my greeting,” Meltsner said. “She smiled her very particular and winning smile. We exchanged a few words. After we talked for a while, she looked down at the pad. She was, she said, writing a Supreme Court brief.

“I said, ‘Well, you should get on with it, then,’” he recalled. “She did.”

Meltsner said Ginsburg was working on a brief for Frontiero v. Richardson, a case in which Sharron Frontiero, a lieutenant in the United States Air Force, sought a dependent’s allowance for her husband. At the time, federal law required husbands to depend upon their military wives for at least a half of their support in order to receive dependent status. Wives of military husbands, however, did not have to meet the same requirement.

Michael Meltsner is the George J. and Kathleen Waters Matthews Distinguished Professor of Law at Northeastern. Photo by Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University

“It was one of the cases she won that dramatically changed American law,” Meltsner said.

Ginsburg was hired to teach procedure, conflicts, and a new course in conjunction with the American Civil Liberties Union on sex discrimination. At the time, Ginsburg was quite active in her work with the ACLU, and made it clear that her work with the organization would continue while at Columbia.

“The only confining thing for me is time,” she told New York Times reporter Lesley Oelsner in 1972. “I’m not going to curtail my activities in any way to please them.”

Meltsner said he sensed “apprehension” bubbling under the surface among his new Columbia Law colleagues over the hiring of outspoken lawyers.

“We were both outsiders to some extent—on the margins—and coming into this law school to make changes,” he said.

A woman, Ginsburg especially was considered an outsider at the time, and Meltsner recalled several colleagues who voiced doubt, or at least ambivalence, about offering her tenure. Before her appointment at Columbia, Ginsburg was a tenured professor at Rutgers Law School. Offering her immediate tenure at Columbia was therefore a necessity, Meltsner said.

According to an interview with the New York Times reporter Oelsner just after her appointment at Columbia, Ginsburg was under no illusions about what lay ahead of her.

“I don’t think I’ll have any problem,” she told the Times. “People will be pleasant on the outside. Some of them may have reservations about what I’m doing, but I don’t think they’ll be expressed.”

For media inquiries, please contact Shannon Nargi at s.nargi@northeastern.edu or 617-373-5718.