They’re planning to build a new space station… at the bottom of the ocean

When we wanted to study space, we built the International Space Station—a place where astronauts could live, work, and conduct long-term experiments without having to return to Earth.

What if we had something similar on the bottom of the ocean?

Fabien Cousteau, a renowned aquanaut, environmentalist, and documentary filmmaker (and grandson of Jacques-Yves Cousteau), has been envisioning exactly that. And Northeastern is helping to make it a reality.

“If it gets built, and I truly hope it does, it will be transformative,” says Mark Patterson, who is the associate dean for research and graduate affairs in Northeastern’s College of Science. “It really will be like the International Space Station at the bottom of the sea.”

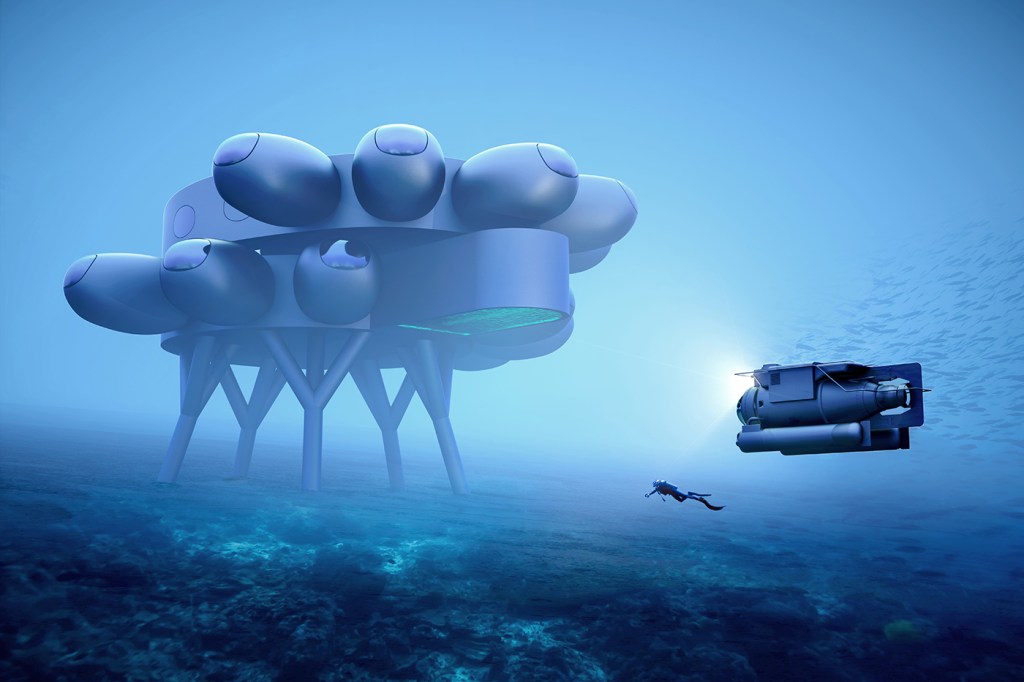

The research station already has a name—Proteus, after an ancient Greek sea god—and a location—60 feet underwater, by a coral reef off the island of Curaçao in the Caribbean. Although the designs are not set in stone, it is planned to be four times larger than any previous underwater habitat, with space for research labs, sleeping quarters, an underwater greenhouse, and a video production facility to livestream educational programming. Northeastern is one of several partners in the endeavor.

Mark Patterson, associate dean for research and graduate affairs in Northeastern’s College of Science, is advising on the scientific program for Proteus. Photo by Northeastern University

Patterson and Brian Helmuth, both professors of marine and environmental sciences based at the Coastal Sustainability Institute in Nahant, are advising on the scientific program for Proteus. The advantage of working from an underwater habitat, Patterson says, is that it gives researchers “the gift of time.”

“If you need to be out in the water column—making your measurements, collecting the weird organisms that are there, doing engineering tasks—and you’re operating from the surface, you don’t have the luxury of time,” Patterson says. “You’re on the clock the instant you hit the water.”

When divers head underwater, the ocean presses in on them—you might have experienced a popping feeling in your ears only a few feet below the surface. That pressure causes the nitrogen in the divers’ lungs to dissolve into their tissues. The deeper they go and the longer they stay there, the more nitrogen dissolves into their bodies.

Nitrogen is an inert gas, so this isn’t really a problem as long as the diver stays at the same depth. But when they return to the surface, and the pressure eases, that nitrogen forms into bubbles like a fizzing carbonated drink, which can cause a dangerous and even deadly set of symptoms known as decompression sickness.

To prevent this, divers must limit the amount of time they spend at depth and ascend slowly to let their bodies adjust. But if they have a way to stay at depth—say, in an underwater research station—they can work all day in the water, for weeks on end, and only have to worry about decompressing carefully at the end of the trip.

“You have unlimited time every day, so you can put in eight to 12 hours a day outside in the water, the same way that astronauts in space can,” Patterson says. “When you have time, you start seeing things that you didn’t see before; you make discoveries you would not have anticipated, because you’re present.”

Patterson has logged 89 days of saturation diving, as it’s called, over the course of 10 missions. Many of those have been in an underwater habitat known as Aquarius, in the Florida Keys. This meant Patterson and other Northeastern faculty and students were perfect scientific partners for Mission 31 in 2014, in which Cousteau and two other aquanauts lived in Aquarius for 31 days straight. Northeastern was a scientific partner for Mission 31, and a team of students and faculty provided support from above and below the water.

Where Proteus truly surpasses its predecessor is that it will have laboratories to process samples, troubleshoot equipment, and run multiple experiments. It’s not just intended to be a base to collect things before they are sent up to the surface—it’s a self-contained underwater research center.

“Aquarius on steroids—that’s what Proteus is envisioned to be; a true underwater laboratory,” Patterson says. “So there would be PCR machines to do DNA sequencing and fully functioning laboratories to look at plankton or microplastics. Or an engineering lab so that if you were working with underwater robotics, or new methods of harvesting energy from the ocean, or aquaculture that you have the tool you need right there.”

Working from Proteus would help marine scientists and engineers to be more productive with the time that they have. It would also allow the aquanauts to reach a world-wide audience, and involve citizen scientists as well as students, such as those from Northeastern’s Three Seas Program. And it would create the opportunity to make discoveries simply by being in an incredible place long enough to look around.

“We used to go out at night after dinner, just to watch the predator show all around the habitat,” Patterson says. “All the lights attract all the plankton, and that attracts the small fish, and that attracts the bigger fish, and then the big predators show up like sharks and barracuda and these giant goliath groupers—they can be up to seven feet long and 1000 pounds when they’re maxed out. It’s quite the show to watch the food chain in action. It makes you feel a little bit insignificant.”

For media inquiries, please contact Shannon Nargi at s.nargi@northeastern.edu or 617-373-5718.