The CDC is no longer in control of COVID-19 hospitalization data. Here’s what that means.

Under a new federal mandate, the COVID-19 data that U.S. hospitals had been sending directly to the Centers for Disease Control and prevention are now being sent to a different central database, using a system run by a private technology firm.

The change raised concerns among public health experts, who warned the new directive might be a move to sideline the CDC, the leading public health agency in the U.S.

Samuel Scarpino, an assistant professor who runs the Emergent Epidemics lab at Northeastern, says that barring a catastrophe, such as computing systems being hacked or destroyed, changing the way data is collected in the midst of a public health crisis is far from ideal.

“It’s a horrible idea—that’s the technical term for it,” Scarpino says. “They’re taking a really complicated process around capturing, organizing, and analyzing data from the hands of individuals that have been doing it their entire lives, and putting it into the hands of individuals that have little to no experience—right in the middle of a pandemic.”

Samuel Scarpino is an assistant professor of marine and environmental sciences and physics. Photo by Adam Glanzman/Northeastern University

The new reporting system is intended to help streamline the process of collecting data, including levels of staffing in hospitals, intensive care units, and personal protective equipment, among other important information about COVID-19 patients.

With the new system, government officials are coordinating the allocation of supplies and drugs, including the only known treatment for COVID-19, remdesivir, which is limited and reserved only for the sickest patients.

Still, public health experts have expressed concerns because the CDC has for decades played an integral role in informing people in the U.S. on how to prepare for and respond to public health crises such as the current pandemic.

Since its inception in the 1940s, the agency has been the leader of collection, analysis, and interpretation of important data to help authorities from different states and cities understand and respond to outbreaks and emergent diseases at the national, state, and local levels.

That is, the agency helps facilitate communication between states which don’t always agree on actions, ranging from how to report data to which measures to take in response to a public health crisis, Scarpino says.

“That’s one of the really critical roles the CDC plays during an infectious disease outbreak,” he says. “It’s a really big deal that these data are being moved out of the CDC, because you have this complicated political relationship between all the states.”

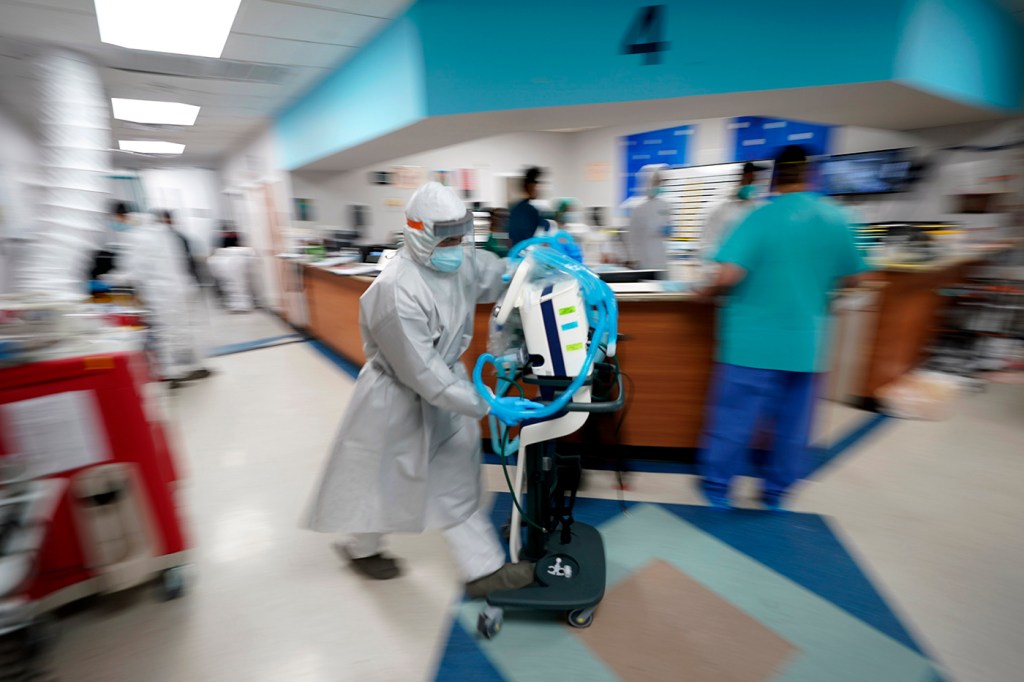

Another concern of changing that data collection process is that medical staff suddenly need to learn a new reporting system, at a time when some hospitals are overwhelmed with COVID-19 patients.

And, Scarpino says, the move could also mean further confusion for researchers, public health agencies, and local authorities who are developing action plans to reopen different sectors of the economy.

“We’re all starting to make decisions around how or if we can reopen K-12 schools, how or if we can safely bring undergraduate students back to campus,” Scarpino says, adding that researchers and school administrators will need to make those decisions even if something goes wrong with the new data-collection process or if the data is unreliable.

The CDC began collecting COVID-19 hospitalization data on a daily basis in March, using a system that has operated for decades to track infectious disease outbreaks.

The move to change reporting systems comes after the arguments of the Trump administration against the recommendations of the CDC to reopen schools.

And it highlights an important problem within the U.S. that has politicized science, and which could cause harm and devalue the input of scientific experts in the eyes of the public, Scarpino says.

“What this means is that a process that should be as largely apolitical as possible, is being politicized as so many other things around this pandemic have been,” Scarpino says. “This is going to make it much more difficult for individuals to understand and contextualize the kinds of biases that may be present in the data that we’re looking at.”

For media inquiries, please contact Marirose Sartoretto at m.sartoretto@northeastern.edu or 617-373-5718.