Here’s how policing in the US could be reformed

The cycle has become common and familiar. An unarmed Black man or woman is shot or choked to death. The police officers involved in their deaths are often placed on paid administrative leave while an investigation is conducted. Outrage builds among the public while an inquiry into the officers’ behavior goes on for months, sometimes years.

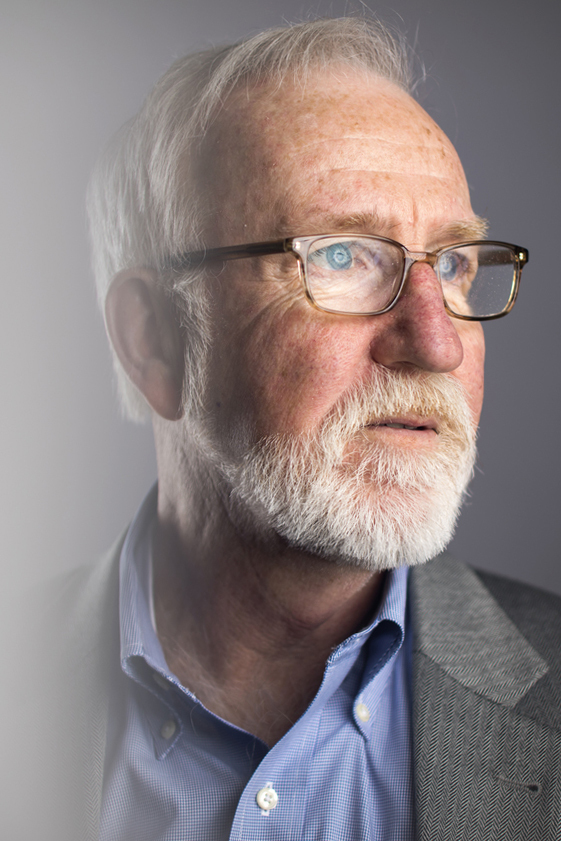

Jack McDevitt is a professor of the practice in the School of Criminology and Criminal Justice in the College of Social Sciences and Humanities and director of the Institute on Race and Justice at Northeastern. Photo by Adam Glanzman/Northeastern University

So it was a departure from the norm when Derek Chauvin, the former Minneapolis police officer seen in a video with his knee on George Floyd’s neck, was almost immediately arrested and charged with second-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter. Officers Thomas Lane and J.A. Keung, who helped restrain Floyd, and a fourth officer, Tou Thao, who stood by, were also charged on Wednesday with aiding and abetting murder.

Jack McDevitt, director of Northeastern’s Institute on Race and Justice, said that while Minneapolis Police chief Medaria Arradondo’s firing of Chauvin and the other three officers involved in Floyd’s killing signals an ‘unprecedented’ response, police departments must do more to change the way they operate.

“What this police chief said was, ‘Look, I don’t care that this is how we have done things in the past. This was such a heinous event. And the police officers who watched it are also at fault because we don’t allow trained police to allow crimes to go on even if it’s committed by another police officer,’” said McDevitt, a professor of the practice in the school of criminology and criminal justice at Northeastern who studies hate crime and racial profiling. “The city took the input of the chief, took the unprecedented step of saying, OK, you’re all fired. We know we’re going to go to court, but we’ll fight it in court.”

Law enforcement agencies must heed the demands of the protestors, said McDevitt, and act to bring about structural change to departments. That begins with increasing the diversity of the police force, and actively recruiting members of the Black community, he said.

“You got to go in and say to people, ‘We’re going to value you as a person; you’re going to have the same rights to a promotion; you’re going to have the same chances to succeed,’” he said. “Today, how many African American kids think that?”

Other reforms are necessary to address racial injustice and inequalities within the culture of policing, McDevitt said. He supports training programs that help officers recognize and address underlying bias, as well as monitoring their interaction with the public. McDevitt is also a proponent of creating a system that allows officers to report other officers’ misconduct.

While the camaraderie and solidarity of law enforcement is important in helping build trust and partnership among officers whose job requires them to work together in often dangerous and tense situations, he said, it can also repress officers from exposing corrupt colleagues.

“We need to break the culture of silence and make it a culture where officers report misbehavior and agencies respond to it,” McDevitt said.

Equipping civilians with a legitimate role in looking over police misconduct cases is also crucial, he said. In the early 1990s, McDevitt was a part of a special commission that reviewed police misconduct and use of force in the Boston Police Department that resulted in the firing of the city’s commissioner, Francis M. Roache. One of the commission’s findings, said McDevitt, was that a small number of officers was responsible for the majority of the complaints from civilians.

“The bad apples are killing people,” he said.

If citizens had played a role in the Minneapolis Police Department’s system of accountability, said McDevitt, perhaps Chauvin would not have evaded disciplinary action despite racking up 17 complaints during his nearly two decades with the department.

“That’s unheard of in a police department,” he said. “Generally, an officer will have one or two complaints in their whole career. Whether or not they’re sustained, that should be enough of a red flag to say this person needs help.”

Jeff Liu, commander of the East Palo Alto Police Department and a 19-year-veteran, could only agree. On Wednesday, he joined protesters in the Northern California city’s Bell Street Park by kneeling in silence, the stillness eclipsed only by the whirring of a police helicopter hovering above and a symphony of honking car horns driving past.

“They should have been charged,” said Liu from behind a black cloth mask, in between hugs and elbow bumps with the dispersing protesters. “They stood there and did nothing. We have it in our policy manual that if you see another officer doing that, you will intervene. You will get that officer off that person.”

Liu said it was hard for him to stay on one knee for so long. Several times he felt himself fighting the urge to switch, but he stayed still.

“I wanted to know how it felt,” he said. “All my weight was on my knee, and that was not an easy position to maintain. I don’t know how you could possibly kneel like that without putting all your weight on that knee. It just makes it that much worse.”

Added Liu, “I think we can all agree that what happened in Minneapolis was not right.”

It’s possible, said McDevitt, that the unrest that has been ignited in neighborhoods across the country stems from feelings of frustration and anxiety that people were already experiencing from the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as larger societal issues.

“Now all of a sudden you take African American and Latino communities and say, and by the way, in addition to the health crisis and the economic crisis, you’re still subject to a justice system that is biased and unfair,” McDevitt said. “It’s really asking people to put up with an awful lot at once.”

At the same time, he said, COVID-19 has revealed racial health and economic disparities in the U.S. We’ve learned that there are certain groups of people who are more likely to have chronic diseases. We’ve been made aware that there are groups of people that are more likely to either not have a job or have a job that doesn’t pay a living wage. And we’ve been reminded that there are people who are subject to police misconduct and police violence.

Much of the time, it happens to be the same group of people, said McDevitt, so it’s worth contemplating how we got here.

“One of the things we have to do is to understand that there are people in our society who are disadvantaged across systems,” he said. “How do we now cut across systems and share information from the medical field to the economic field to the justice system to say how are we going to be able to identify the most vulnerable in our society and support them?”

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.