Models can predict how COVID-19 will spread. What goes into them, and how can we use what they tell us?

Countries around the world are grappling with how to handle the COVID-19 pandemic. Some of the best tools global leaders have at their disposal are epidemiological models, which predict how the disease will spread. But what goes into these models, and how do leaders and public health authorities use this information?

On Thursday, Joseph E. Aoun, president of Northeastern, will sit down for a conversation with Alessandro Vespignani, the director of Northeastern’s Network Science Institute, who is leading one of the major efforts to model this disease.

This is not Vespignani’s first epidemic. His team’s forecasting models for various diseases, including the 2014 outbreak of Ebola in West Africa and the potential spread of the Zika virus in the U.S. in 2016, have informed the decisions of health agencies across the globe. In the case of COVID-19, his model is one of several guiding the policies of the White House.

The key to Vespignani’s work, and what makes it different from traditional modeling methods, is including the human element. His model accounts for the incubation period of the disease, how contagious it is, and the method of transmission. But it also incorporates factors that influence human behavior, such as transportation, social interactions, and the availability of medical resources in different areas.

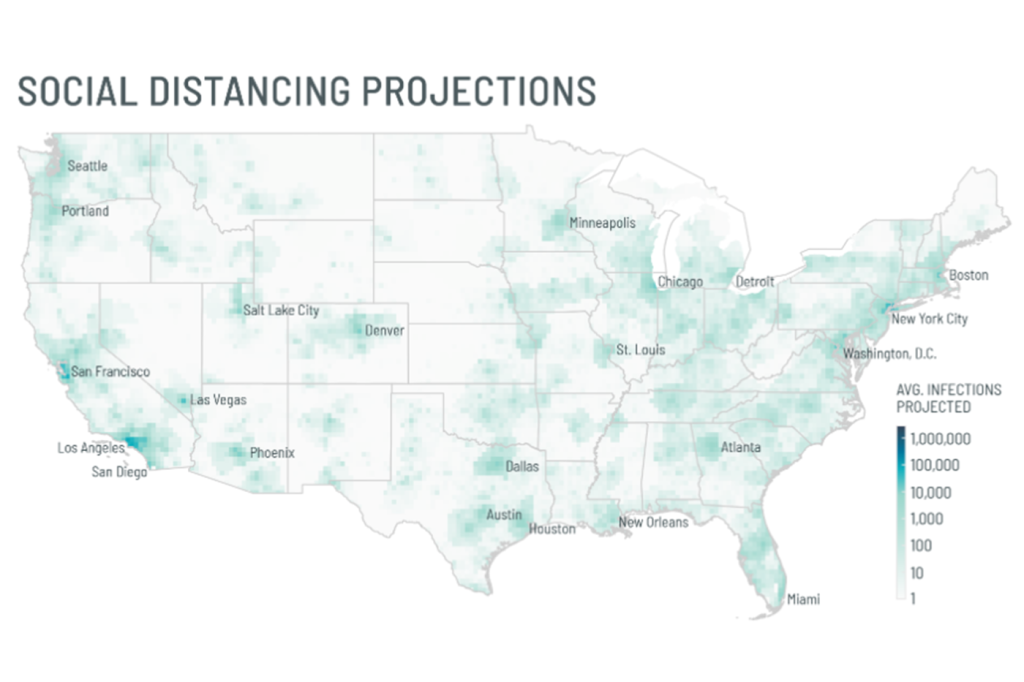

Recently, his team has been using anonymous location data from mobile devices to gauge how the behavior of people in the U.S.—how much they are traveling, commuting patterns, number of contacts with new people—has changed in response to physical distancing measures.

His research also revealed that SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, was already circulating in major U.S. cities in January—long before most of us were paying attention.

All this information feeds back into the model to predict the likely spread of the disease and, most importantly, how specific policies could help bring it under control.

Listen in on Thursday at 2:30p.m. on Facebook Live.

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.