How can the US ensure an accurate 2020 census without going door to door?

Every 10 years, the United States government sets out to count every single person living in the country—something it’s been doing since 1790. The information is used to determine how critical resources, including congressional representation and hundreds of billions of dollars in federal funding, are allocated. This year poses a particular challenge for federal officials, though: How do you count people during a pandemic?

“The assumption this year has been that a great many people will submit their census forms online and/or use other kinds of digital media to ensure they’re counted,” says Ted Landsmark, distinguished professor of public policy and urban affairs at Northeastern, and director of the Kitty and Michael Dukakis Center for Urban and Regional Policy.

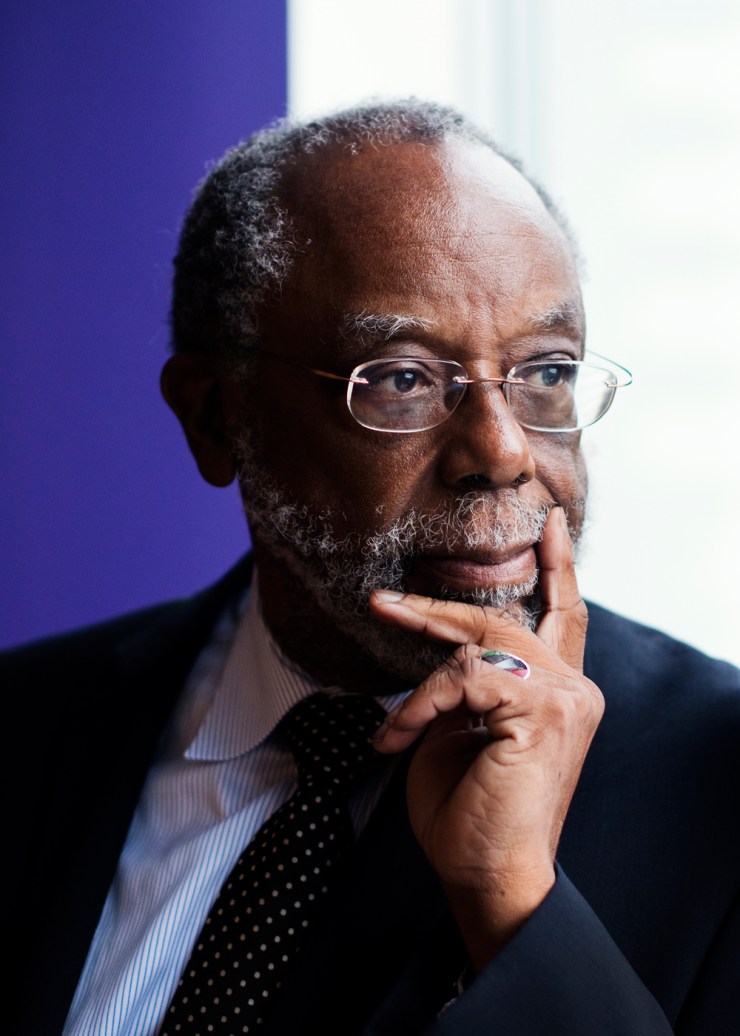

Ted Landsmark is distinguished professor of public policy and urban affairs in the College of Social Sciences and Humanities, and director of the Kitty and Michael Dukakis Center for Urban and Regional Policy. Photo by Adam Glanzman/Northeastern University

The assumption rests on the notion that everyone has easy and reliable access to a computer and to the internet, but that’s not the case in many parts of the U.S., Landsmark says. And while scores of local organizations had been preparing for months ahead of the census to reach people in those communities, much of their effort has been stymied by public health protocols that require physical distance and isolation.

“One of the things that’s come obvious during the COVID-19 pandemic is that generally underserved communities and rural communities where there’s not a high level of digital accessibility aren’t being as well-served,” Landsmark says.

That puts the pressure back upon traditional counting techniques, Landsmark says. Any other year, census-takers could have overcome the disparity by going door to door and hand-counting people. But efforts to slow the spread of the novel coronavirus have made that option an impossibility.

“As long as census-takers aren’t going to be able to interact face-to-face, it would almost certainly lead to a significant undercount in communities of color and rural communities—communities that are underserved and most in need of the federal resources that flow from a census count,” Landsmark says.

Undercounting the population of any community could lead to the loss of a congressional seat in the district, or more, as well as potentially billions of dollars of federal funding, Landsmark says.

An undercount would reduce the amount of money a municipality has for health services, education, transportation, unemployment and other job support programs, youth programs, Community Development Block Grants used for housing, infrastructure improvements, and a range of other federal government investments, he says.

The census is taken every 10 years, but such underinvestment could have a snowball effect well beyond the next decade, Landsmark says. Federally funded early education programs would suffer, as well as healthcare services for children—creating a generation of adults who are more likely to be unemployed and suffering from health deficiencies than their peers, he says.

“Any lack of investment now because of an undercount that reduces federal funding going into underserved communities has long-term negative implications for communities that could easily run into the billions of dollars,” Landsmark says.

So, how do federal officials prevent such undercounting without the option of door-knocking? Landsmark says the next best option is that people fill out the form by hand and mail it in.

But, the U.S. Postal Service is beleaguered by the effects of COVID-19, too. Mail volume has fallen drastically since this time last year and the agency says it needs an $89 billion in order to continue operating past September, a bailout that doesn’t seem likely to come, according to information from the Trump administration.

Short of the mail service, Landsmark says, the U.S. Census Bureau may need to rely upon specific federal agencies, such as the Federal Emergency Management Agency, to invest in community-based outreach.

“As the initial census-filling period starts to wind down, we’ll need heavy participation on the part of community organizations to assure that people complete and submit those census forms.”

For media inquiries, please contact Jessica Hair at j.hair@northeastern.edu or 617-373-5718.