From a health clinic in Haiti to the school nurse’s office in Massachusetts, she’s caring for community

Not so long ago, Keziah Furth worked on a landfill.

Not at a landfill, but on top of one, at a community health clinic in the Jubilee Blanc section of Gonaives, Haiti. Built in a neighborhood that served as the “town dump,” Furth says, Klinik Jubilee started as a scrappy—but essential—healthcare center for nearby residents who had until then relied upon themselves or weekly visits from a nurse for their medical needs.

“There just wasn’t anything, in terms of facilities,” Furth recalls.

Furth graduated from Northeastern’s nursing program in 2008, and spent the next eight years in Haiti working at various care centers and helping to get Klinik Jubilee up and running. Now, she’s the school nurse at The Rashi School, a private school in Dedham, Massachusetts.

“In a lot of ways, it feels like I existed in one world and now I exist in a completely different world, and ‘never the twain shall meet,’” Furth says, borrowing a line from the poet Rudyard Kipling.

At the clinic in Haiti, she once treated a man who’d cut his leg with a machete while he’d been harvesting sugar cane. Because he lacked proper first aid, his wound had become badly infected with maggots, Furth recalls. She and her colleague at the clinic spent an hour and a half each day for a week patiently removing them with tweezers.

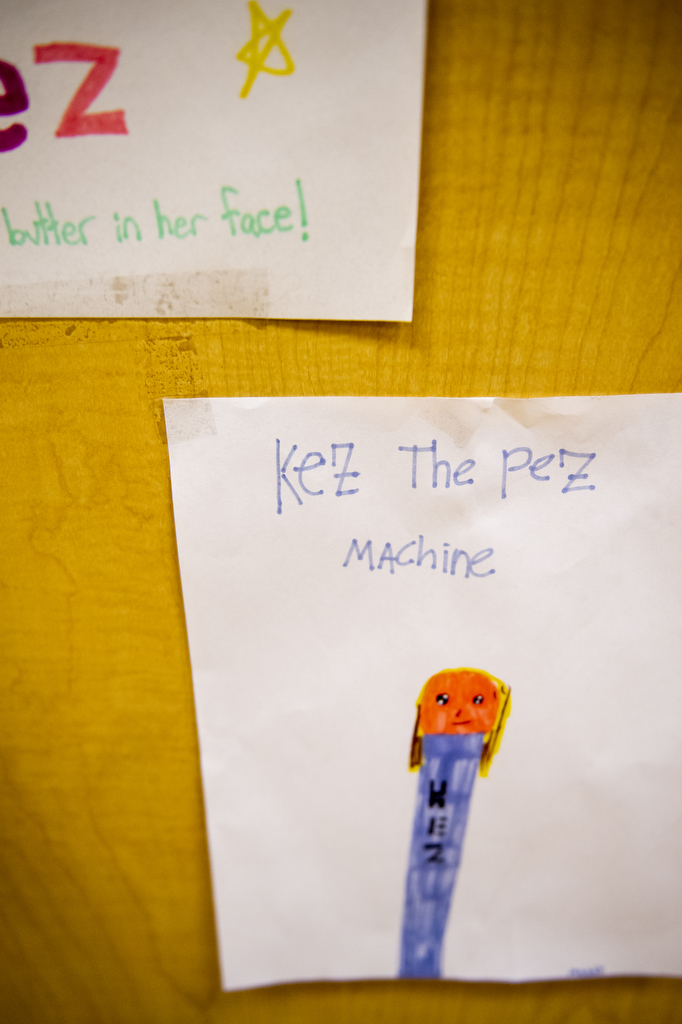

At The Rashi School, Furth’s bright office is filled with drawings from students, and she has access to all the medical supplies she could need—at school, and in the U.S. more generally, she says.

“The world of Haiti that I was in was so completely different from the life we have here, and all the luxuries we have here,” she says. “It can be difficult to mesh the two.”

Furth worked in the Caribbean country for the first time while she was on co-op as a Northeastern student. She lived and worked in an orphanage for teenagers, during which time she became fluent in Haitian Creole.

“Mostly, I was serving as an older sister and mentor for the teens,” she says.

Furth quickly fell in love with the work and the communities she worked in, and “moved back right after graduation,” she says.

She lived in Port-au-Prince after graduating, this time at a home for malnourished infants and toddlers. She also worked in a health clinic under the supervision of a physician’s assistant from the U.S. For three and a half years, Furth did home visits in the nearby neighborhoods, and generally tended to the medical needs of her community, she says.

“It was wonderful; I got to see kids grow up and families grow and mature,” she says.

Eventually, it was time to move on, and Furth moved up the coast to a smaller city: Gonaives. Friends of Furth’s were working at a school there. Once per week, a nurse would set up in one of the rooms in the school, and provide care for the neighboring communities. Around the time Furth moved to the city, that nurse quit her post, so Furth stepped in.

She and her friends built a separate medical facility that could be open all week: Klinik Jubilee. Each day, they focused on a different need—Mondays were for general consultations; Tuesdays for prenatal check-ups and aid for malnourished children; Wednesdays for blood-pressure check-ups; and Thursdays were catch-all days for assorted medical needs and follow-up appointments, Furth says.

Once the clinic was up and running, Furth taught community health classes for adults and young adults. She taught basic first aid and more advanced courses for community members who showed particular interest or skill.

She trained some people to work in the clinic, and trained others to become healthcare advocates in their own communities, Furth says.

“It was really, really rewarding work,” she says.

After a total of eight years in Haiti, though, it was time to return home, Furth says. She saw peers working in other non-government organizations getting burned out or disillusioned with the work they were doing in the country, and didn’t want to get to that point, herself.

Now, at The Rashi School, she tells the story of her experience whenever she gets the chance. When inquisitive students visit her office, she’ll tell them of the people she met and the work she did. When the school’s annual philanthropic fundraiser, Tamchui, was looking for organizations to highlight, she nominated Klinik Jubilee—and the students raised $3,242 for the facility.

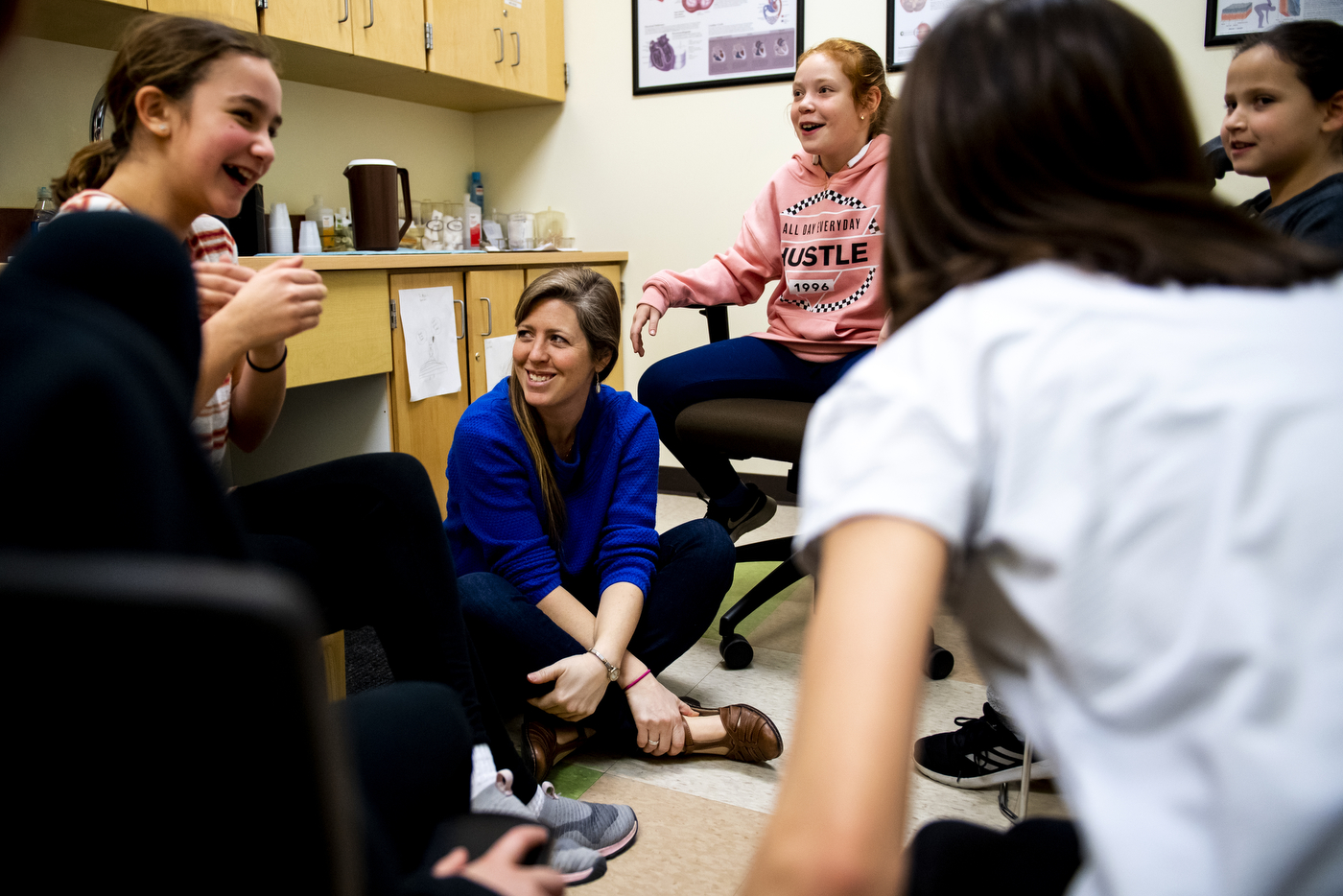

Furth teaches an after-school yoga class at Rashi, and uses the opportunity to answer her students’ questions about Haiti, and to teach the budding yogis about compassion and empathy. That is, when school is in session. Like schools across the world, Rashi has been closed since mid-March, 2020, in order to help slow the spread of COVID-19.

“We’re trying to educate kids, and that’s so much more than math, reading, and writing,” Furth says. “We want them to grow up to be young people who can change the world and really have an impact. So, if even one of these kids is inspired to go do something to touch the world, that would make me really, really happy.”

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.