A custom staircase builder learns the trade in Australia, one step at a time

BRAESIDE, Australia—Chase Bivona considers himself one of the luckiest people he knows: “I always say to myself in the morning: ‘It’s another beautiful day to be a stair builder.’”

The unfailingly cheerful Bivona, 22, from Exeter, Rhode Island, is showing a pair of visitors around the huge S&A Stairs workshop in an industrial park in suburban Melbourne, where he’s doing a six-month co-op as part of his civil engineering studies at Northeastern.

There’s wood stacked in every conceivable location, the smell of sawdust and glue hangs in the air, and it’s hard to hear over the noise of sawing, sanding and the beeping of forklifts.

Loud Aussie rock blasts out from bass-heavy speakers, in an apparent attempt to penetrate the workers’ hearing protection.

Bivona has traveled to the other side of the world to learn production and management techniques he hopes can take his father’s 35-year-old custom stair building business, Hardwood Design Inc., to the next level.

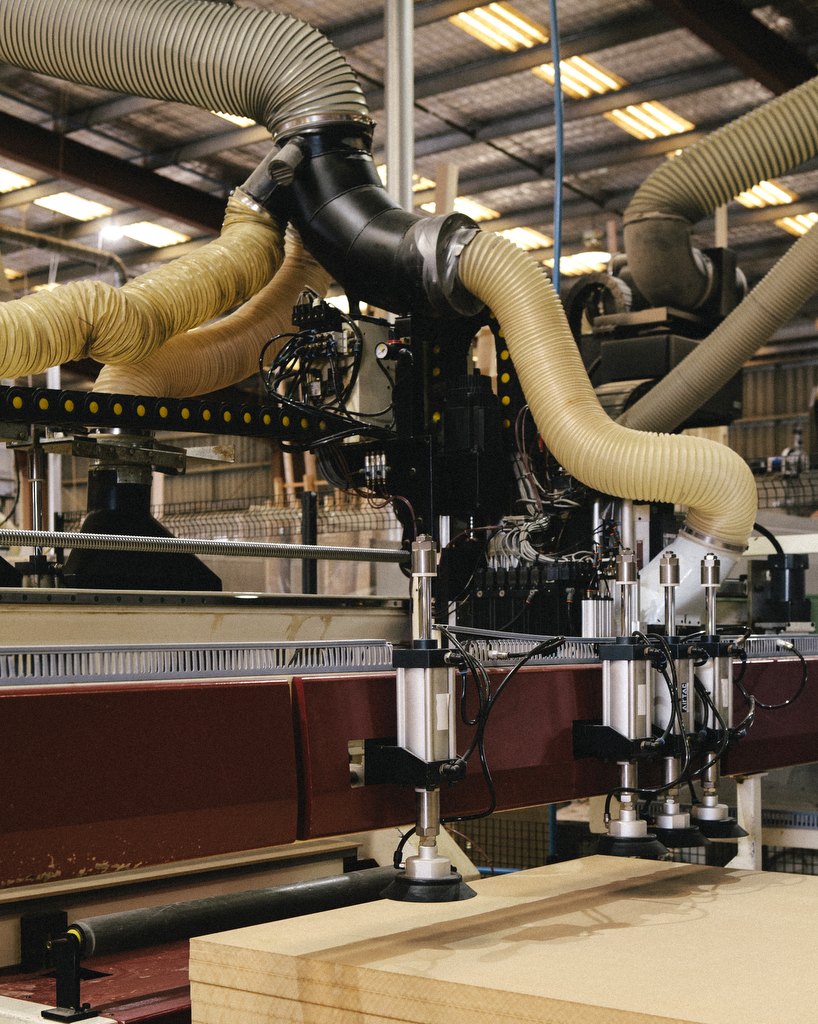

Bivona points out the huge computer numerical control machine, with its long conveyor belt, that precuts most of the wooden components.

He stops off at the assembly station, in front of a long beam with triangles cut out of it.

It’s called a stringer, and it’s one of the three major parts of a staircase.

“The stringers are like the beam underneath the stair, the treads are what you step on and the risers are the vertical pieces,” he explains. “The CNC machines cut all this stuff. But it ends up not being perfect.”

He grabs a chisel and goes to work smoothing out the rough edges in the corner of one of the triangles.

“This really needs to be a perfect 90 degrees, so I have to go in with a chisel and make it nice,” he says.

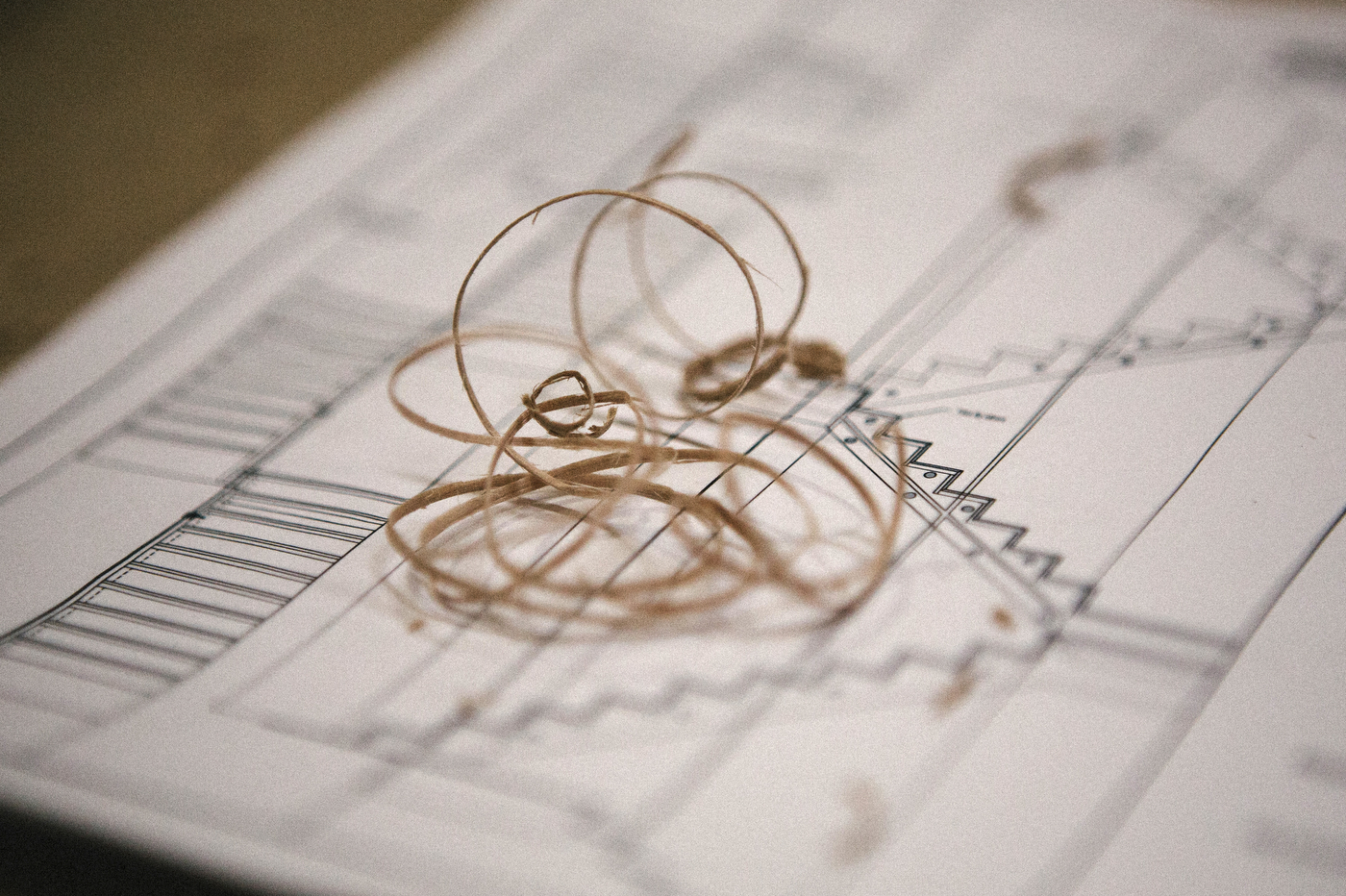

Bivona spent the first two months here in the workshop, but he’s currently working in the front office, learning how to plan jobs using a 2D drafting software package called Autocad—though he still helps out in the workshop once a week if they’re busy.

His final two months will be learning to work the computer numerical control machines.

“I’ve also been having a lot of business development conversations with the managing director and senior management staff,” he says.

It’s these conversations that could prove the most valuable for his father’s business.

S&A and Hardwood Design Inc. may operate on different scales, but both are family-run businesses that emphasize their dedication to quality.

Custom stair building is something of a dying art. It’s a true craftsman’s pursuit—a highly technical, yet creative job, building the finely detailed centerpieces of high-end homes.

“You can really make a statement with it,” Bivona says. “Picture walking in the front door and you’ve got an incredible curved staircase staring you in the face. That’s why some architects design homes around these things.”

Jobs can take anywhere from a few days for a straight flight, to six months, for a five-story set of elliptical stairs.

It’s a trade that requires military-level precision, from transforming the architect’s plans into something practical and achievable, to measuring everything on site down to a fraction of an inch, then building the components in the workshop to transport and assemble on site.

It was the foreman on a stair installation job back in Boston who first suggested S&A for Bivona’s third and final co-op. He says he was already familiar with the company’s work on Instagram.

S&A is like his father’s 25-person company on steroids—a fourth-generation outfit with almost 200 employees that built the grand staircase at Australia’s Parliament House and worked on Sydney’s Olympic Village. It operates across four locations in two states.

They’ve grown by using assembly line production techniques and technology to manufacture large numbers of stairs each week—which still resemble the high-quality craftsmanship of years gone by.

Unlike Hardwood Design, which builds and assembles as much as possible in its workshop, S&A prepares the components and sends them in Ikea-style flatpacks to be assembled on site.

S&A is able to undertake many more jobs at the lower end than Hardwood Design, and this high-volume work now accounts for about 65 percent of their output.

“That’s the biggest difference,” says Bivona. “My dad’s company does the slow, highly-detailed work, and he doesn’t chase the lower end stuff, but the company in Australia does both and does it so fast and efficiently, it’s crazy.”

“This is an incredible experience because this company does a lot of things that (Dad) doesn’t, that I can bring back.”

Bivona’s father, Bill, agrees that the six-month co-op could be “the mother lode” for Hardwood Design.

“They have been so good to him with regards to sharing details from manufacturing to design to management,”he says. “I like to think that we reciprocated.”

Bivona has been around the family business since he was a toddler, sleeping under his mother’s desk some days.

Bill recalls him as a 13-year-old, starting the workday by sweeping the workshop floor.

“Everyone at the shop used to tell me he was a perfect ‘Mini-Me,’” Bill says. “Like me, he has a real passion for working with wood.”

While the younger Bivona toyed with becoming a lawyer, ever since he was old enough to drive, he has wanted to take over the family business someday.

Bill says he didn’t pressure his son, but admits it’s “every father’s dream.”

“He tells me that he really wants to do this and so it will be up to him to earn the respect and knowledge to the point that he can take over at some point,” he says.

At the age of 22, Bivona realizes he’s one of the lucky ones, to have already found his path in life.

“A lot of my friends, a lot of the kids I go to school with at college, they’re like ‘I don’t really know where I’m going to end up,’ and that’s a really strong point of anxiety in their early 20s,” he muses.

“‘Am I studying the right thing? What am I, what do I want to do?’”

“So I was really lucky to have found this thing I’m incredibly passionate for.”

He introduces Nick Acquroff, the youngest of the three brothers who run S&A Stairs.

They’re the fourth generation in the family business in its 99-year history. Managing director Robert Beard also followed his father (a former apprentice who became a partner) into the business back in 1975.

Acquroff initially pursued a career in freelance journalism, before joining at the age of 29.

“Nothing feels like this does, because you belong to something,” he says. “There’s a shared sense of belonging here, and it gives you a really great, strong identity.

“Dad always just said: ‘You do what you want. If you come back, you come back.’ We’ve all come back.”

For Bivona, picking up and moving overseas for six months was a huge decision. Despite the opportunity, he admits he wrestled with feelings of anxiety and doubt about the move.

It was a Northeastern Dialogue of Civilizations trip to South America last year—looking at climate change science and policy in developing countries—that gave him the confidence to take the plunge.

“It really opened my eyes to what’s out there and gave me that travel bug: ‘I gotta get out an explore the world especially while I’m young,’” he says.

And he says it’s turned out better than he’d hoped.

“People in Melbourne are really incredibly friendly compared to what I’m used to. It’s not really normal in New England, to interact with strangers,” he laughs.

Now more than halfway through his co-op, Bivona has mixed emotions at the thought of returning home in December.

“It’s been better than I could have imagined as far as learning things at work and being challenged—and even outside of work,” he says.

“I think when it comes time for me to leave, it’s going to be a little bit tough.”

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.