Impeachment inquiry runs into Constitution’s sparse language on congressional subpoenas

The White House recently announced that it would not cooperate with the congressional impeachment inquiry, calling it, in a letter to Democratic House leaders, an illegitimate effort “to overturn the results of the 2016 election.”

The main reason the White House considers the impeachment inquiry illegitimate, according to White House counsel Pat A. Cipollone, is that the House never formally voted for it. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi announced during a Sept. 24 press conference that the House would open a formal impeachment inquiry, and that was that.

“Your contrived process is unprecedented in the history of the Nation,” Cipollone wrote to Pelosi.

That the decision is unprecedented is true, says Dan Urman, a scholar of Constitutional law at Northeastern, but that doesn’t make it illegal. The Constitution doesn’t require that the full House pass a resolution before the House committees start gathering evidence, he says.

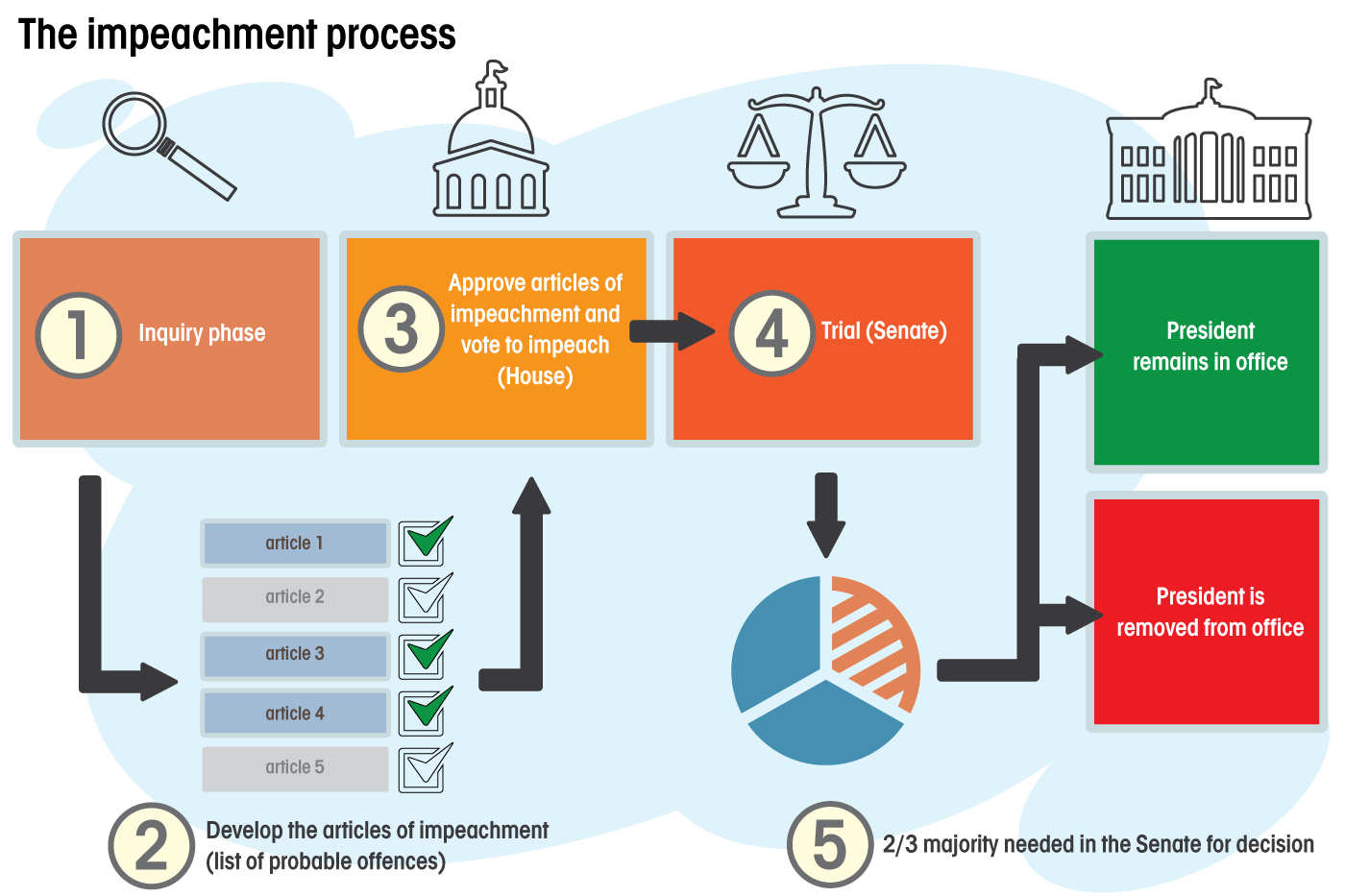

Graphic by Gregory Grinnell/Northeastern University

The Constitution provides very little legal framework for impeachment at all, leaving plenty of room for interpretation.

“Impeachment is an emergency, break-the-glass procedure in our political system,” Urman says. And while the impeachment processes of Andrew Johnson, Richard Nixon, and Bill Clinton all began with a full House vote, there is nothing in the Constitution that requires it, he says.

Why is there so little guidance in the country’s founding document on one of the most serious political procedures its government can enact? Urman says it’s because the Constitution’s framers simply didn’t anticipate the country would be so deeply divided by its party politics.

“I’m suggesting that the founders thought that Americans would be best protected by a separation of powers,” Urman said. “Ultimately what we have now is a separation of parties, not of powers.”

As of this writing, the administration has mostly stuck to its word:Many of the officials subpoenaed by Congress to provide information related to an investigation into the president’s alleged request for dirt on a political opponent from the Ukrainian government. There are a few notable exceptions, though. A former White House aide, Fiona Hill, testified on Monday. And Gordon Sondland, who is the U.S. Ambassador to the European Union—is scheduled to testify, despite being advised not to by the U.S. State Department.

What happens when someone defies a Congressional subpoena? Congress has three options for recourse, Urman says, and we’re about to find out which they choose.

Congress has an “inherent power” that gives it the authority to use the Sergeant at Arms of the U.S. House of Representatives to “hold and imprison someone who’s in contempt of Congress” until that person complies, Urman says.

That’s the first option for recourse, though members of Congress haven’t used this power since the early 1900s, Urman says.

The second option is that members of Congress can make a criminal contempt case to the Department of Justice, Urman says. The problem with this option for Democrats who want to push ahead with the inquiry is that the Department of Justice reports to the president “and has already shown that it’s on the same page as the president when it comes to this inquiry,” he adds.

The third, and most likely option, he thinks, is that Congress sends the case to the federal court system for resolution.

“The challenge here, of course, is that the courts tend to move pretty slowly, so there might not be a resolution until 2021 or ’22,” Urman says, far too late for House representatives who likely want a resolution before the 2020 presidential election.

Democrats in the House have also hinted at a fourth option: The articles of impeachment with which Richard Nixon was charged included one that he failed to provide information to House inquirers.

For media inquiries, please contact Marirose Sartoretto at m.sartoretto@northeastern.edu or 617-373-5718.