Can nature reduce the damage caused by hurricanes?

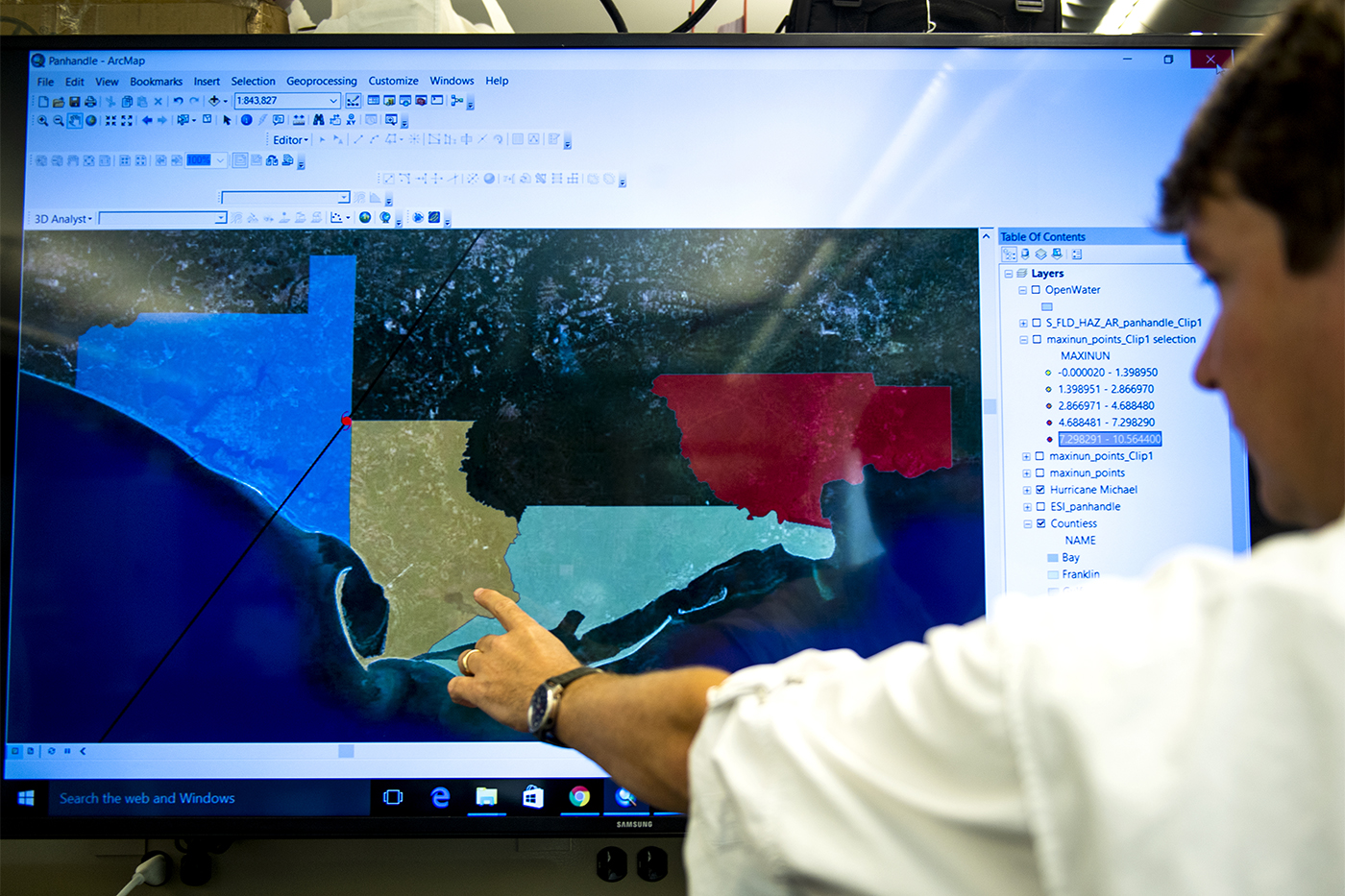

On Oct. 10, 2018, Hurricane Michael ripped through the Florida Panhandle with winds that whipped up to 160 miles per hour, resulting in the deaths of more than 40 people and causing over $25 billion in damage. But coastal and upland green spaces, such as marshes and forests, may have prevented the storm from wreaking even more havoc.

When we think of the first line of defense against hurricanes, seawalls might come to mind before all else. These massive structures, often made of concrete or metal, loom along coastlines to shield communities from crashing waves and floods.

“In some places, we need these walls,” says Steven Scyphers, an assistant professor of marine and environmental sciences at Northeastern. They can provide an immediate barrier to protect specific streets, for example, and modern engineers have developed designs that have further enhanced the walls’ resistance to the impact of certain waves.

But people tend to underestimate the power of non-engineered solutions that may complement seawalls. One of the best defenses against natural forces could be nature itself.

Scyphers has teamed up with Christine Shepard at The Nature Conservancy and U.S. Naval Academy engineering professor Tori Tomiczek to investigate the impacts of natural ecosystems—particularly marshes—on the damage inflicted by Hurricane Michael.

Shepard, who is director of science for The Nature Conservancy’s Gulf of Mexico program, says nature-based solutions, like protecting green spaces and restoring salt marshes, can and should be part of planning for and recovering from coastal storms. “We have quantified the benefits provided by nature for other storms like Hurricane Sandy in the Northeast and Hurricane Ike in Texas, and each study further makes the case for including nature-based approaches when planning to reduce risk to people and property along the coast,” Shepard says.

“There’s been a lot of research that shows that natural habitats like salt marshes are far more environmentally beneficial than seawalls and [other] artificial structures,” Scyphers says. “What we’re focused on with this study is understanding the role of these different types of structures in coastal protection, and that’s an area where a lot more science is needed. We hope this work will help communities prioritize ecosystem restoration efforts in areas that may reap the greatest benefits.”

For proof of nature’s strength, first consider the fact that Florida’s wetland ecosystems exist at all. The tall, billowy grasses in the marshes of the Panhandle and the deeply rooted mangroves of the Florida Keys have endured and evolved in regions that have been battered relentlessly by hurricanes and other harsh weather conditions.

And unlike seawalls, which gradually deteriorate, marshes, mangroves, and other coastal habitats have the capacity to recover and regenerate over time. Through storm after storm over thousands of years, these natural wonders have demonstrated their resilience.

Some scientific evidence suggests that this resilience can help surrounding communities limit damage from storms. In 2017, for instance, just after Hurricane Irma struck the Keys, Scyphers and his student researchers collaborated with Tomiczek to study the protective effects of the area’s mangroves.

Ultimately, Scyphers says, they found that “the houses that had mangroves in front of them had significantly less damage compared to houses that had artificial structures.”

Funded by The Nature Conservancy through a grant from the Walton Family Foundation, their upcoming study will determine if similar protective effects can be found in the Panhandle, where salt marshes predominate instead of mangroves. Past research offers reasons to be optimistic.

“Marshes perform a lot of similar functions [to mangroves],” Tomiczek says. Studies have shown that marshlands act like a giant sponge, absorbing water to reduce flooding. They also provide a buffer for waves. As water crashes over or through a marsh’s rough grasses, its waves lose energy and weaken by the time they reach farther inland.

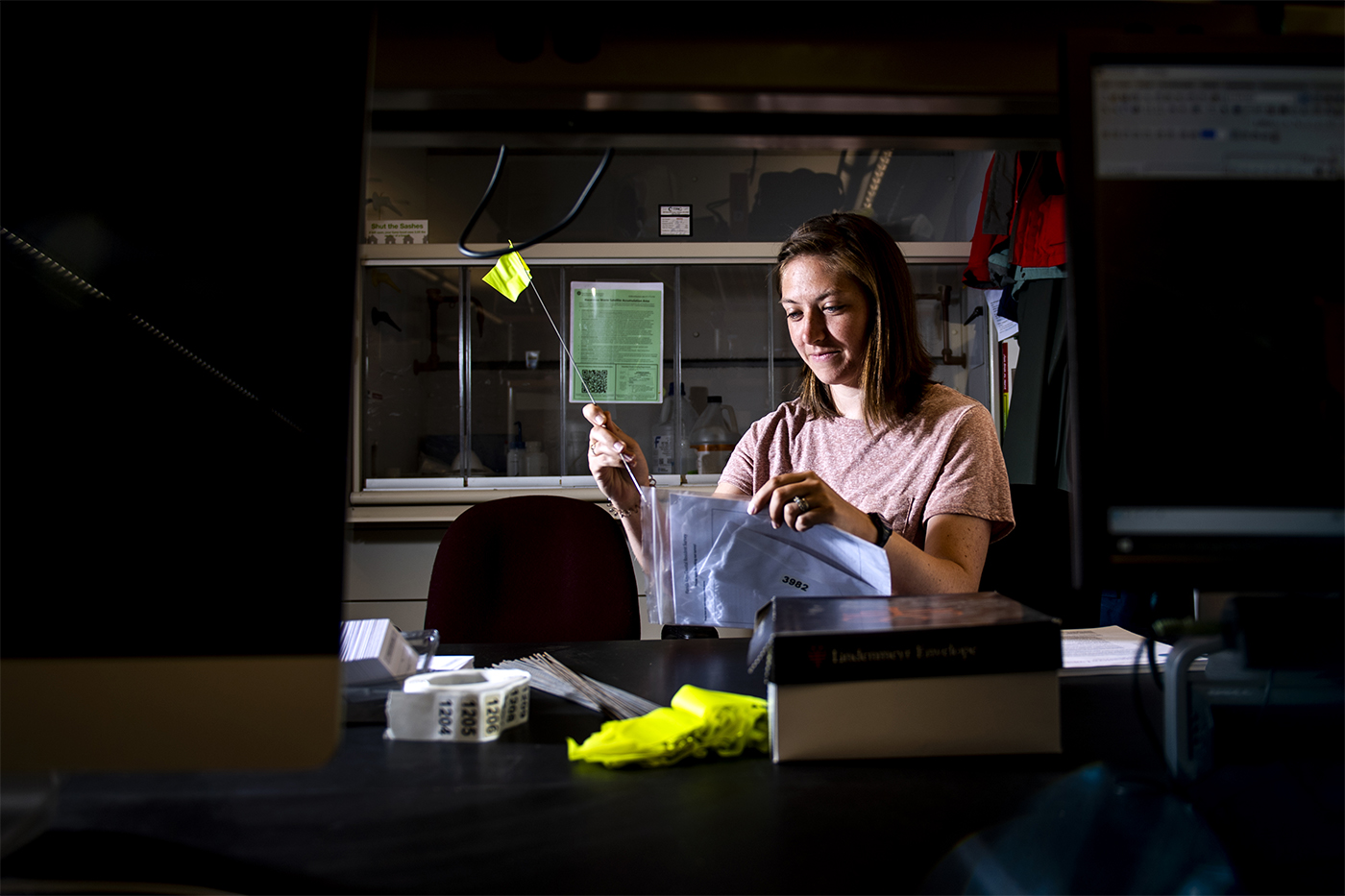

But their study won’t just take a closer look at the marshes, says Kiera O’Donnell, a doctoral candidate at Northeastern who is working with Scyphers to conduct this research. It will also seek to capture the stories and the struggles of people affected by Hurricane Michael.

Researchers are conducting surveys of residents across the Florida Panhandle. They’ll ask some questions about the visible signs of destruction, like collapsed walls and caved-in roofs—but then they’ll move beyond that, working to reveal hidden mental, social, and financial repercussions.

The survey includes questions such as:

—How frequently do you visit with your neighbors before versus after the storm?

—Did your employment change?

—Do you feel that you have mentally recovered?

After they receive the results, the researchers will assess whether proximity to natural barriers helped reduce the structural, social, and mental impacts caused by the storm.

When they examined the Keys about a month after Irma hit the region, though, Tomiczek said that it wasn’t the damage that struck them the most, but the community’s ability to overcome hardship.

Tomiczek remembers she was surrounded by crumbling walls, shattered windows, splintered doors. Then she saw the mangroves. They had already begun to rebuild, their newly sprouted branches rising amid the brokenness.

A family sat outside the empty slab that used to be their home, Tomiczek recalls. They had lost everything—yet, somehow, they had not. Somehow, they had hope. “We’ll be back,” Tomiczek remembers the family saying. “It might take some time, but we’ll be back.”

Scyphers says his research will help determine whether the resilience of coastal and upland ecosystems bolsters the ability of surrounding communities to recover more quickly from hurricanes.

“We want our science to help people make responsible, sustainable decisions, whether those are environmentally based or societal,” he says. “The number one goal for our work is that we provide scientifically reliable advice that helps communities recover and develop more sustainably.”

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.