Shellfish geneticists help bivalve hatcheries breed better oysters to survive warming oceans

Humans have been selectively breeding animals for thousands of years: cows that produce more milk, pigs that grow to larger sizes, sheep that have thicker wool. Genetic testing, which has become faster and more accessible, has made this process even easier.

So why not do the same with oysters?

Oyster hatcheries already try to breed animals with characteristics that make them more marketable, like meatier bodies or specific shell shapes. But the briney bivalves currently face threats from warming oceans and several parasitic diseases. The traits that could help them survive are harder to spot.

Now, a group of shellfish geneticists is trying to help the oyster industry select for the traits that will make oysters both thrive in their environment and melt in your mouth.

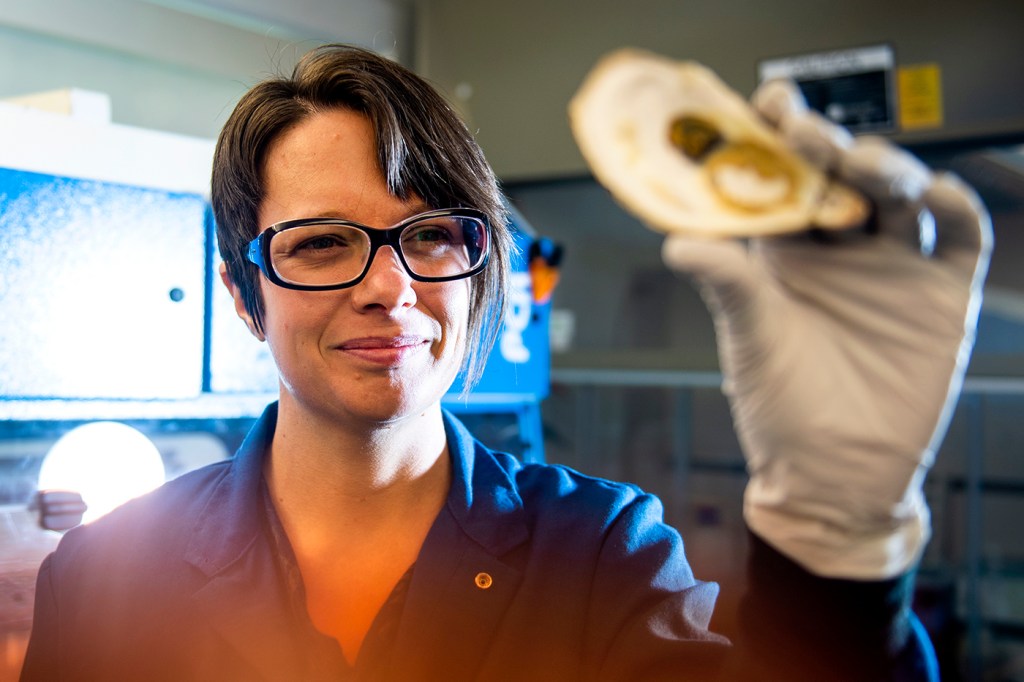

“There’s a lot of room for improvement to breed a better oyster,” says Katie Lotterhos, an assistant professor of marine and environmental sciences at Northeastern. “We’re bringing in new expertise and new tools into the industry that will help increase productivity.”

Lotterhos is part of the Eastern Oyster Breeding Consortium, a group of researchers from 12 institutions, which recently received a grant from the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission to develop new tools to help oyster hatcheries choose the right oysters to breed.

The group is specifically focused on the eastern oyster, Crassostrea virginica, which ranges from the Atlantic coast of Canada to the Gulf of Mexico. While these animals are all the same species, they have different adaptations depending on the region where they are found, Lotterhos says. Animals in the south may be better able to handle warm water, while those growing near the mouths of rivers might be adapted to water with less salt in it.

“So instead of just thinking about one trait, like disease, we’re trying to breed for multiple traits,” Lotterhos says.

Oysters are what scientists call broadcast spawners, which means that when the timing is right, they eject eggs and sperm into the water around them and leave the rest to chance. This doesn’t make it easy for growers, whose farms are typically located in coastal areas open to the ocean, to ensure that the right oysters are reproducing, or even staying on the farm.

Instead, most growers purchase “seed” (baby oysters about the size of your fingernail) from hatcheries, where oysters are encouraged to spawn in a more controlled environment. With the help of genetic analysis, hatcheries could provide oyster seed that is specifically tailored to particular regions and resistant to certain diseases, ensuring that more of the oysters survive to adulthood.

In individuals of the same species, the vast majority of their genetic code is identical. But scattered throughout that code are occasional variations called single nucleotide polymorphisms (which researchers write as SNPs and pronounce as “snips”).

Members of the consortium previously sequenced the entire genomes of eastern oysters growing as far south as Louisiana and as far north as Maine. Lotterhos and her colleagues will be analyzing these sequences to figure out which variations are tied to important oyster traits.

They will be compiling the small segments of DNA that contain those variations on a tool called a SNP chip (“snip chip”). Oyster hatcheries will be able to use the SNP chip to determine which of their oysters have these same desirable traits.

“Once you know which genetic markers contribute to certain traits, like disease resistance, you can use individuals that have those markers in the breeding process,” Lotterhos says.

The hope is to breed a better oyster able to cope with changing ocean conditions and also appeal to restaurants and other customers. The slimy, salty experience of eating a raw oyster may not be for everyone (Lotterhos admits they’re not her favorite food), but for the bivalve buff in your life, this research could provide a ray of hope on the half shell.

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.