What LSD, mushrooms, and toad venom taught Michael Pollan about spirituality

The smoked venom of the Sonoran Desert toad is “the Everest of psychedelics,” Michael Pollan was told. The moment he lifted the pipe to his lips and inhaled its vaporized crystals, he felt a roaring rush of energy filling his head—and terror, as if everything that he had been was no more.

“That was not a very happy experience,” says Pollan, who was exposed to LSD, psilocybin mushrooms, and other psychedelics while researching his latest book, How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence.

It was not enough for Pollan to experience his own apparent disintegration; he also had to bring his readers along with him. It was a quantum leap for a man, and a (not quite) indescribable passage for a journalist. In the book, he compares his encounter with the toad to the Big Bang in reverse:

Rushing backward through fourteen billion years, I watched the dimensions of reality collapse one by one until there was nothing left, not even being. Only the all-consuming roar.

This was followed, to his relief, by an equal and opposite reaction.

Pollan will be sharing his experiences at Northeastern’s 2019 Ruderman Lecture: What Can Psychedelics Teach Us About Spirituality? Hosted by Northeastern Ruderman Professor Lori Lefkovitz, it will be held Tuesday at 6 p.m. at East Village and will be streamed live.

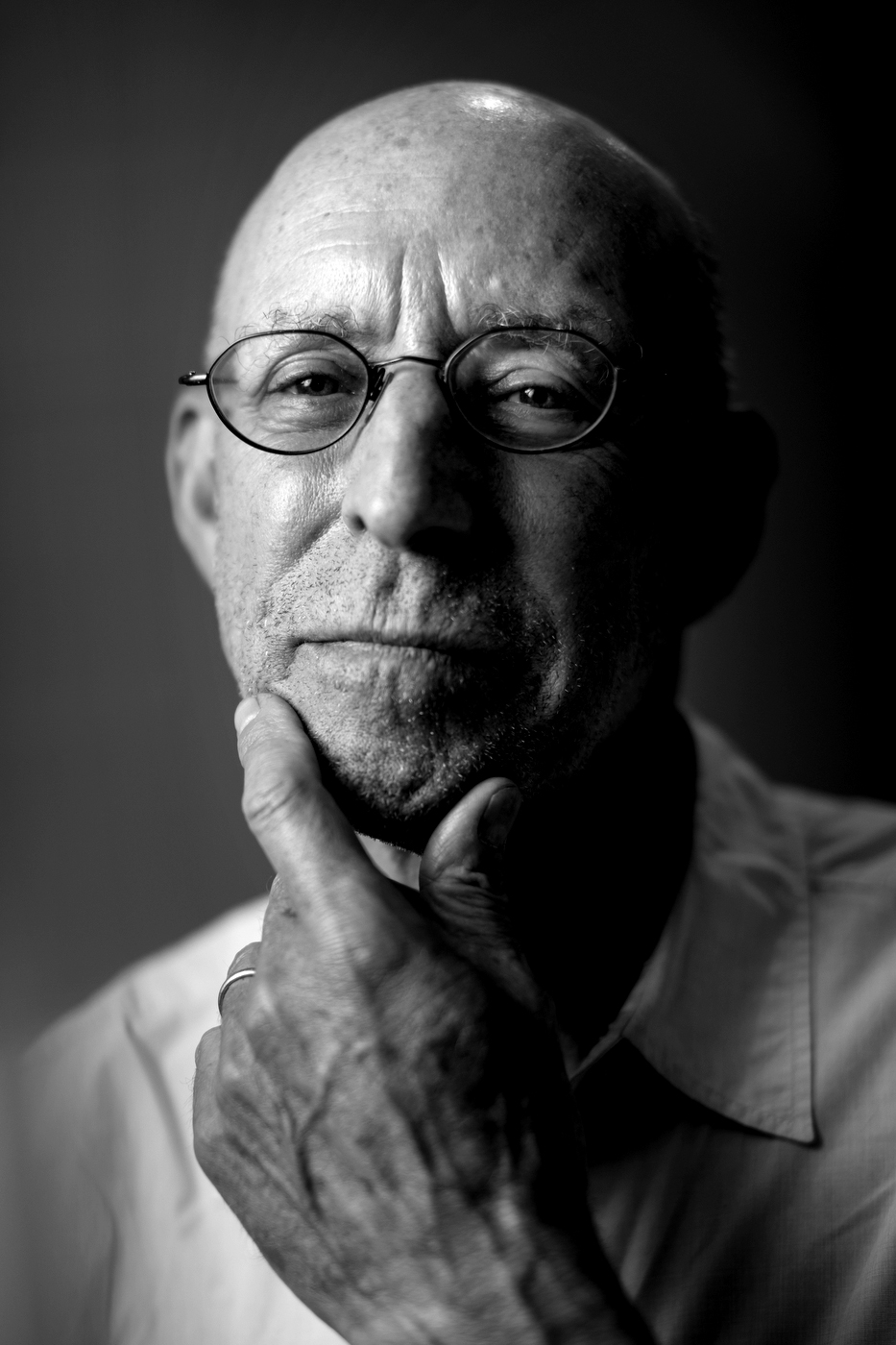

Psilocybin mushrooms, which he ate with bites of chocolate, introduced Pollan to a world of sunlight and color, of liquid transformed into sparkling diamonds. Photo by Adam Glanzman for Northeastern University

Pollan has written 10 books, and their arc tells a story of his evolving fulfillment. In Second Nature: A Gardener’s Education, he explored his relationship with nature in the modern-day world. For A Place of My Own: The Architecture of Daydreams, he designed and built a one-room house in which he would write many of his ensuing best-sellers on food, including the award-winning The Omnivore’s Dilemma: A Natural History of Four Meals.

His recent investigation of psychedelics was something else. LSD and other drugs were deemed illegal and dangerous following the counterculture 1960s era, which was personified by the self-aggrandizing Harvard psychologist Timothy Leary, who urged followers to “think for yourself and question authority,” and “turn on, tune in, drop out.”

Both Pollan and his publisher recognized the commercial risk of this provocative subject.

“How many of my readers are going to be interested in something that’s kind of fringy?” Pollan says from his office at Harvard, where he teaches nonfiction. “As it turned out, a lot of people interested in food were interested in psychedelics. They saw a common denominator that I hadn’t seen, which was health: They trusted me to write about nutritional health, and that translated, in their minds, to being trusted to write about mental health.”

“The Ruderman Family Foundation is committed to advocating for mental health and shattering the stigma that surrounds mental health,” says Jay Ruderman, president of the foundation. “We are excited to have bestselling author Michael Pollan as the keynote speaker for the Morton E. Ruderman Memorial Lecture, and to hear about his exploration into his own mental health and wellbeing.”

Pollan also found himself investigating spiritual health. Psychedelics open users to natural and supernatural visions and experiences that can help people who are dealing with addictions and terminal diseases. The influence of psychedelics can connect them to a larger world that transcends the five senses, enabling them to see their place in it.

All of Pollan’s psychedelic trips were supervised by experienced guides who were granted anonymity in his book. While lying on a mattress with eyeshades and listening to rhythmic, natural music replete with the sounds of rain showers and crickets, LSD led him along a terrain of beaches and mountains that were recognizable and ever-changing as he reviewed his life experiences with his wife and their son.

Psilocybin mushrooms, which he ate with bites of chocolate, introduced him to a world of sunlight and color, of liquid transformed into sparkling diamonds. His own being gave way to a sheaf of Post-it sized papers that scattered in the wind—without conjuring panic or fear in him. His obliteration continued, until he had been liquefied and dispersed like paint; and then he was greeted by a parade of the people he had known whose deaths he had failed to properly mourn.

At night he would dictate pages of memories, which enabled him to share his experiences.

“The recall is remarkable. It’s really vivid,” Pollan says. “I used to think the opposite of spiritual was material. And I realize that’s not really right. The opposite of spiritual is egotistical. To the extent that you can diminish the role of the ego, you become a more spiritual person—more connected, less defended.”

Throughout his psychedelic trips, Pollan experienced epiphanies of love, which, he acknowledges, can ring banal. Some of his visions left him crying. As he recovered from the abject nothingness set forth by the venomous toad, he experienced a profound sense of gratitude for his being.

“I’m not an advocate out there fighting that we’ve got to legalize psychedelic drugs,” Pollan says. “I have disappointed a lot of activists in the psychedelic space by not taking a more forceful position.

“But I am an advocate for more research. It’s a new subject. I’m still in the exploration phase, as opposed to the conclusion phase.”

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.