Global resilience expert at Northeastern University says scientists, engineers, and city planners need to collaborate to prepare for the next Hurricane Dorian

Hurricane Dorian wreaked havoc in the Bahamas, where it killed more than 40 people and destroyed thousands of homes and buildings. Then it hit North Carolina, where it stranded 800 people on Ocracoke Island because of storm surges that flooded roads, houses, and businesses. And a tornado spawned by Dorian on North Carolina’s coast leveled countless trailers and mobile homes that once dotted the beach town of Emerald Isle, making it uninhabitable for many longtime residents.

Stephen Flynn, who directs the Global Resilience Institute at Northeastern, says scientists, engineers, and city planners need to work together in order to prepare communities to withstand and recover from natural disasters of this magnitude. He discussed how the institute is helping cities, states, and Caribbean nations prepare for the next catastrophic storm.

What does “resilience” really mean?

Resilience is about addressing the need to better anticipate and adapt to risks, to nimbly recover from disruptions when they happen, and to “bounce forward” by building back better and smarter. We need to do that at multiple levels and from multiple angles. If you approach it as a technical problem, you’re likely to miss the human dimensions. Tackling it requires the humanics learning model that President Aoun has been advancing, [which integrates three new literacies—understanding technology, understanding data, and understanding what it means to be human]. And we have to move beyond just doing the research within academia that generates resilience best practices. Those practices will not be widely adopted without there being incentives to move beyond the status quo—that’s why engaging with the market, regulators, and public sector practitioners is so important.

How are Northeastern researchers working with the Global Resilience Institute to improve the ability of people and places to prepare for, respond to, and recover from natural disasters?

A central challenge that we find with advancing resilience is being able to understand the complex interdependencies among systems. This is why the work of our colleagues at Northeastern’s Network Science Institute led by Alessandro Vespignani is such an important research capability that we are leveraging.

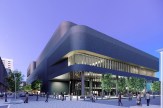

Stephen Flynn, director of the Global Resilience Institute. Photo by Brooks Canaday/Northeastern University

At the Global Resilience Institute, we have over 100 faculty affiliates who are engaged in resilience-related research across all nine colleges at Northeastern. These include Jerry Hajjar, CDM Smith Professor and Chair of Civil and Environmental Engineering, and Taskin Padir, associate professor of electrical and computer engineering and director of the Robotics and Intelligent Vehicles Laboratory. Together we have been working on an early-stage research project that demonstrates the potential to deploy drones to conduct automatic damage assessments of critical infrastructure after a disaster.

For some time we’ve been able to fly drones and collect data by placing sensors on them. But who’s going to process all that data? If it takes a human being to interpret what drones are seeing, then emergency responders will have to be diverted from other tasks to conduct these post-disaster assessments. This project brings together in an integrated way the drone, the sensors, the data the sensors generate, and the knowledge of structures and engineering expertise to create algorithms that can analyze without human intervention whether a bridge or other key asset is safe after a disaster. Accomplishing this will free up first responders to focus on their lifesaving responsibilities.

How does the Global Resilience Institute apply its research to help communities around the world?

Most recently we have been working with the city of New Orleans, which has been on the frontlines of the growing risk that urban areas face from extreme weather events. The people of New Orleans understand why resilience is such an urgent imperative having been knocked down so many times, especially after Hurricane Katrina. But they keep getting back up and have much to teach the rest of us.

We’ve also been working with the state of Maine, helping them to develop an economic development strategy that simultaneously advances their economic and resilience goals to include coastal adaptation to climate change.

On the global front, we have been moving offshore with the Island Resilience Initiative. This effort involves drawing on researchers who are a part of the Global Resilience Research Network that we launched in 2018 and is made up of 30 universities and research institutions from around the world, including several based in the Caribbean. The goal is to help inform and advance the overall preparedness of people who live on islands like Puerto Rico and the Bahamas, where they face increasing storms, rising seas, and long-standing structural challenges.

What can we do to improve the ability of infrastructure to withstand and recover from natural disasters?

An essential stepping off point is to map out how critical things are connected to other critical things. Here is one example: In Boston we have worked with MassPort, the Massachusetts Emergency Management Agency, the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority, the U.S. Coast Guard, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, National Grid, and others on understanding the likely impact of storm surges on the transportation and energy sectors that Boston relies on. We found that each sector had a good understanding of what such an event would do to them. But they had little awareness of what the effects would be on the other sector that they mutually rely on, which translated into some real hiccups for their emergency plans.

Based on that work, we know that if Hurricane Dorian had come north to Boston and brought the kind of storm surge it had on the Bahamas and the Outer Banks of North Carolina, it would be catastrophic. Many of the city’s electrical substations are in low lying areas that include the South Boston Power Complex, which is the backbone of the T. Storm surge will likely damage much of the port infrastructure, which will prevent ships arriving with aviation fuel, diesel oil, heating oil, and liquified natural gas. Without those supplies, backup generators would start running out of fuel and go dark. The tunnels to Logan Airport, the New England Aquarium, and much of the Blue Line would be inundated as well.

Understanding and planning for this kind of risk is not so much a difficult science or technical problem as it is a choreography challenge. It is not a natural act for infrastructure owners and operators to come together to examine their interdependencies. This is a where Northeastern is positioned to play an important role that transcends research. We help bring local, state, federal, and private sector players to the table and help them to better prioritize what measures they can and should be taking before, during, and after the next disaster strikes.

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.