Nearly eight million tons of plastic are missing from our oceans. New research shines some light on what may be happening.

Northeastern professor Aron Stubbins has a mystery to solve: We seem to have misplaced nearly eight million metric tons of plastic.

That’s the estimated amount of plastic waste spilling into the world’s oceans each year, yet more than 98 percent of it is unaccounted for. How could it simply vanish? Stubbins has a culprit in mind: sunlight.

Over time, says Stubbins, the sun’s powerful ultraviolet rays strike large pieces of plastic floating in the ocean and break them into fragments about the size of a sesame seed or smaller, which scientists call microplastics. As sunlight continues to beat down on these microplastics, it degrades them into dissolved carbon. Eventually, they dissolve completely, and presto! No more plastic.

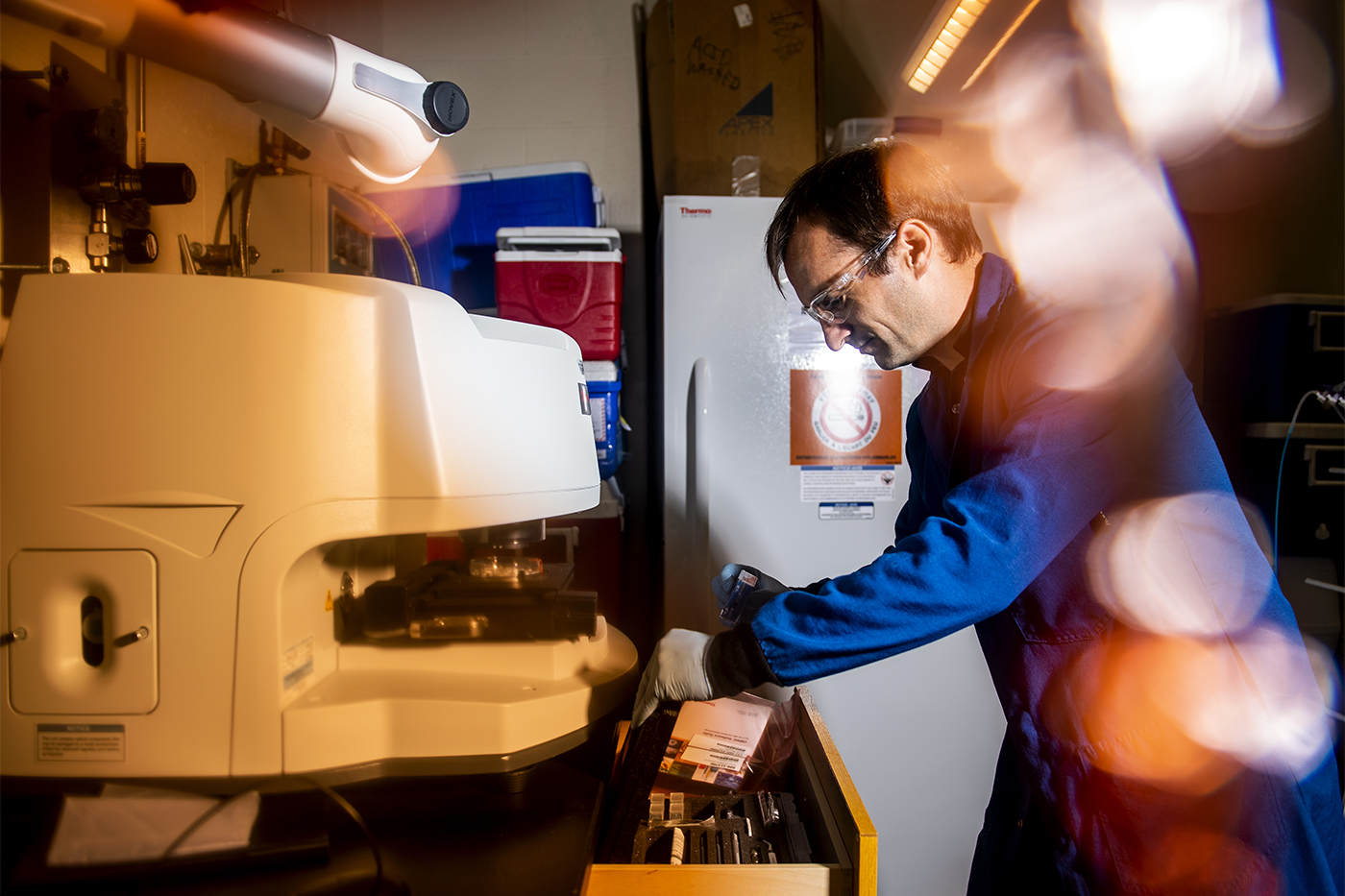

Together with doctoral student Lixin Zhu, Stubbins studied this phenomenon by floating microplastics in seawater under artificial ultraviolet rays produced by a “sun in a box,” a device that mimics sunlight. Sure enough, a couple months’ exposure to the light increased the amount of dissolved carbon in the water and made those tiny plastic particles even tinier.

“This is good news,” says Stubbins, who was recently awarded a grant from the National Science Foundation to study the problem of the disappearing plastic, “but it should be tempered. Sunlight’s not going to solve all our problems.”

One issue is that the sun isn’t as effective at degrading certain types of plastics. For instance, while a five-millimeter piece of Styrofoam would disappear after just a few months of exposure, polyethylene—one of our most abundant plastics—would take “decades to centuries” to break down.

He also points out that only plastics that float will dissolve in this manner.

“Other [plastics] will just sink, and if they get buried in sediments—either at the bottom of the oceans or in soils, like plastics we put in landfills—they will probably stay as big plastics for much longer,” says Stubbins, who holds joint appointments in the departments of marine and environmental science, chemistry and chemical biology, and civil and environmental engineering. “They’re much slower to degrade in the dark, so it might be thousands of years before they become microplastics. If plastic ends up in an environment that’s very stable, it essentially lasts forever.”

And although Stubbins’ experiments suggest that sunlight could be the main remover of the plastics in our oceans, the case isn’t closed yet: Uncertainties could partly explain the missing waste, too. Some of it may be washing up in remote, under-sampled areas, for example—and perhaps eight million tons is an overestimate.

Regardless, Stubbins says, “the better we know the [degradation] processes involved, the more we can understand whether those plastics are likely to build up in the open ocean, on beaches, and in places where they may have cosmetic, human health, or environmental health impacts.”

He’s also investigating how microplastics affect the ocean’s microbe population. Preliminary evidence suggests that some types of microplastic waste promote the growth of bacteria, while other microplastics inhibit that growth, but we still need to work out the details.

For that matter, we aren’t even sure how microplastics directly affect humans.

“They’re finding plastics everywhere,” Stubbins says. “You’re almost certainly breathing in microplastics as we speak, because these small fibers are in the air, too. There’s no strong evidence that they’re bad for us yet, but they’re certainly out there, and we don’t know if they’re having a negative effect in most systems.”

Ultimately, he plans to share his findings with schoolchildren to inspire future generations to think critically about the world around them.

“Hopefully we make the right choices for them now so that the future they inherit is good,” he says—but someday, those choices will be theirs to make.

Stubbins thinks back to his own childhood, as he gazed with wonder into the rivers surrounding his home in the Welsh countryside. At first, he thought only about the creatures he could see. But in time, his focus shifted to the invisible influences that shape the natural world: to the single-celled plants that float in our oceans and the legions of microbes that swim alongside them—and now, to vanishing plastic and ultraviolet rays.

Over the years, he has learned that just because something is out of sight, it shouldn’t be kept out of mind.

“The impact of the processes we can’t see,” he says, “is often greater than the impact of what we can see.”

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.