Smart medical implants could someday advance medicine by communicating wirelessly via sound waves

Pinned to a wall in Tommaso Melodia’s office, next to a stack of wireless technology guidebooks, is a child’s illustration: a smiling heart symbol alongside the word “Papa.” His office is covered with drawings like these, drawings suggesting that this Northeastern engineering professor and father of four has touched the hearts of his children. And someday—through next-generation pacemakers that emit sound waves to regulate cardiac rhythms—he may touch the hearts of many more.

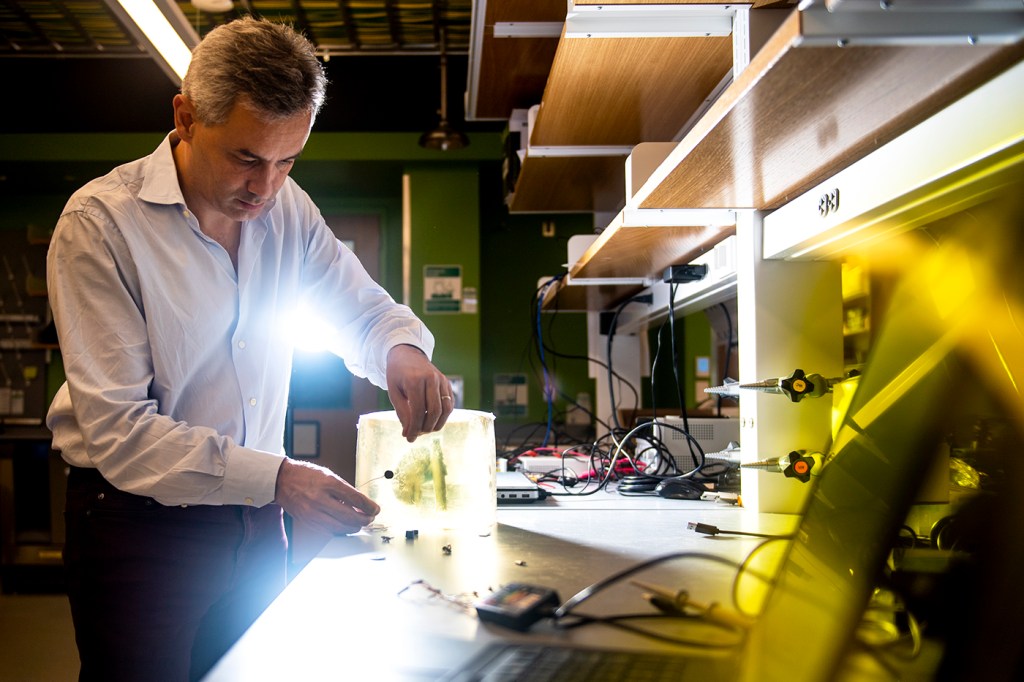

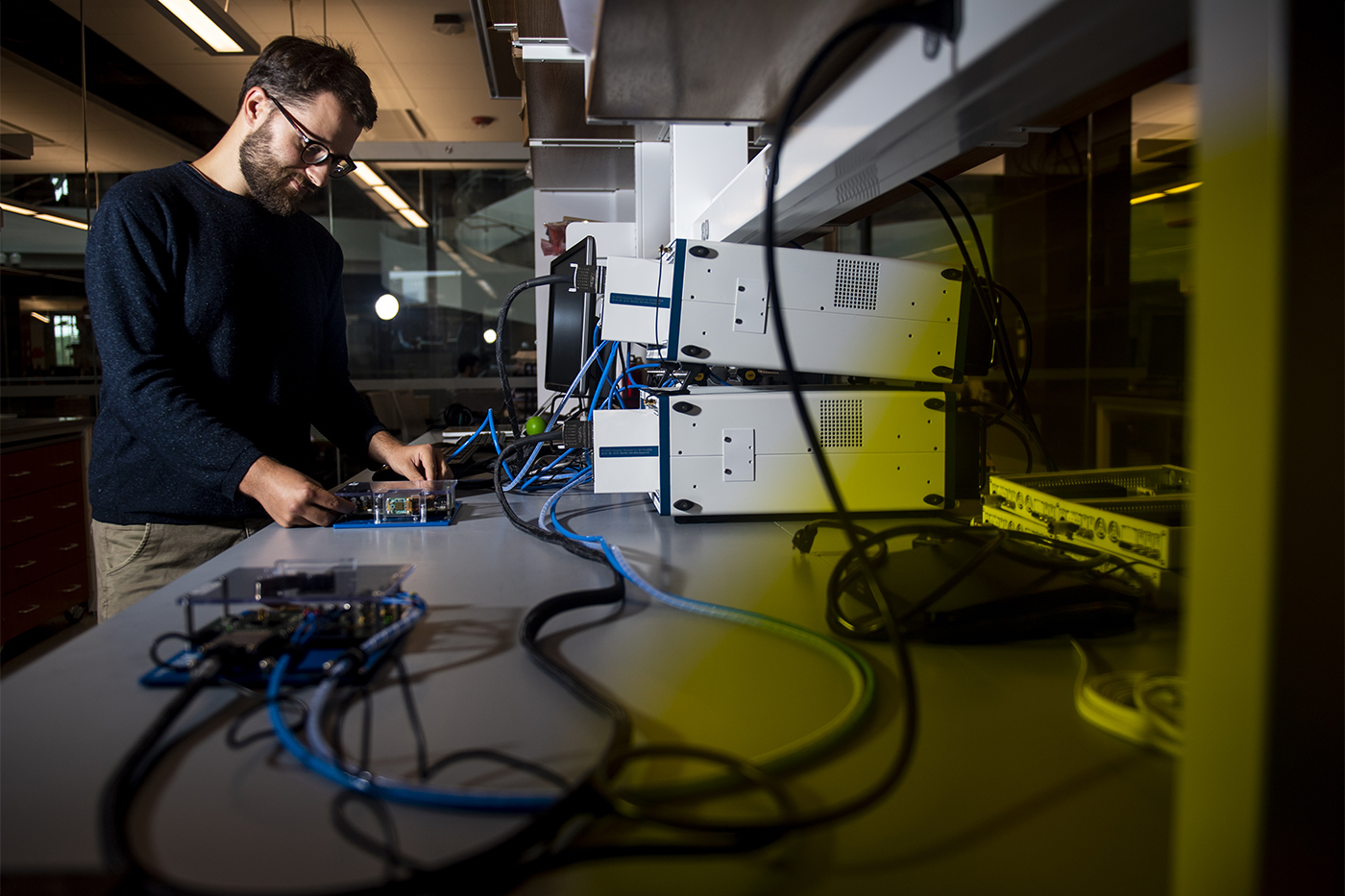

Melodia is working to develop miniature implantable medical devices that sense and communicate wirelessly via sound waves. As the director of Northeastern’s Institute for the Wireless Internet of Things and the founder of the spinoff company Bionet Sonar, he believes this technology could one day treat a broad range of ailments, including diabetes, epilepsy, Parkinson’s disease, and heart conditions.

Traditional pacemakers and other wireless medical devices currently on the market rely on electromagnetic radio waves to communicate. When these waves travel through water, they’re primarily absorbed into it, which means they can’t travel through it freely. (That’s a big deal, if we pause to consider that water makes up 60 to 70 percent of the human body!) As a result, when two portions of a pacemaker need to communicate with each other, they must transmit signals via special wires called leads, which can become infected or break. This energy inefficiency also means that patients must periodically undergo additional surgeries for battery replacements.

For years, Melodia wondered if sound waves—which easily propagate through water and human tissues—were the solution to these problems. In 2012, a grant from the National Science Foundation gave him the opportunity to put this idea into action.

“We’re using ultrasonic waves—frequencies that cannot be heard—to carry information between different implantable medical devices,” says Melodia, who is William Lincoln Smith Chair Professor in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering.

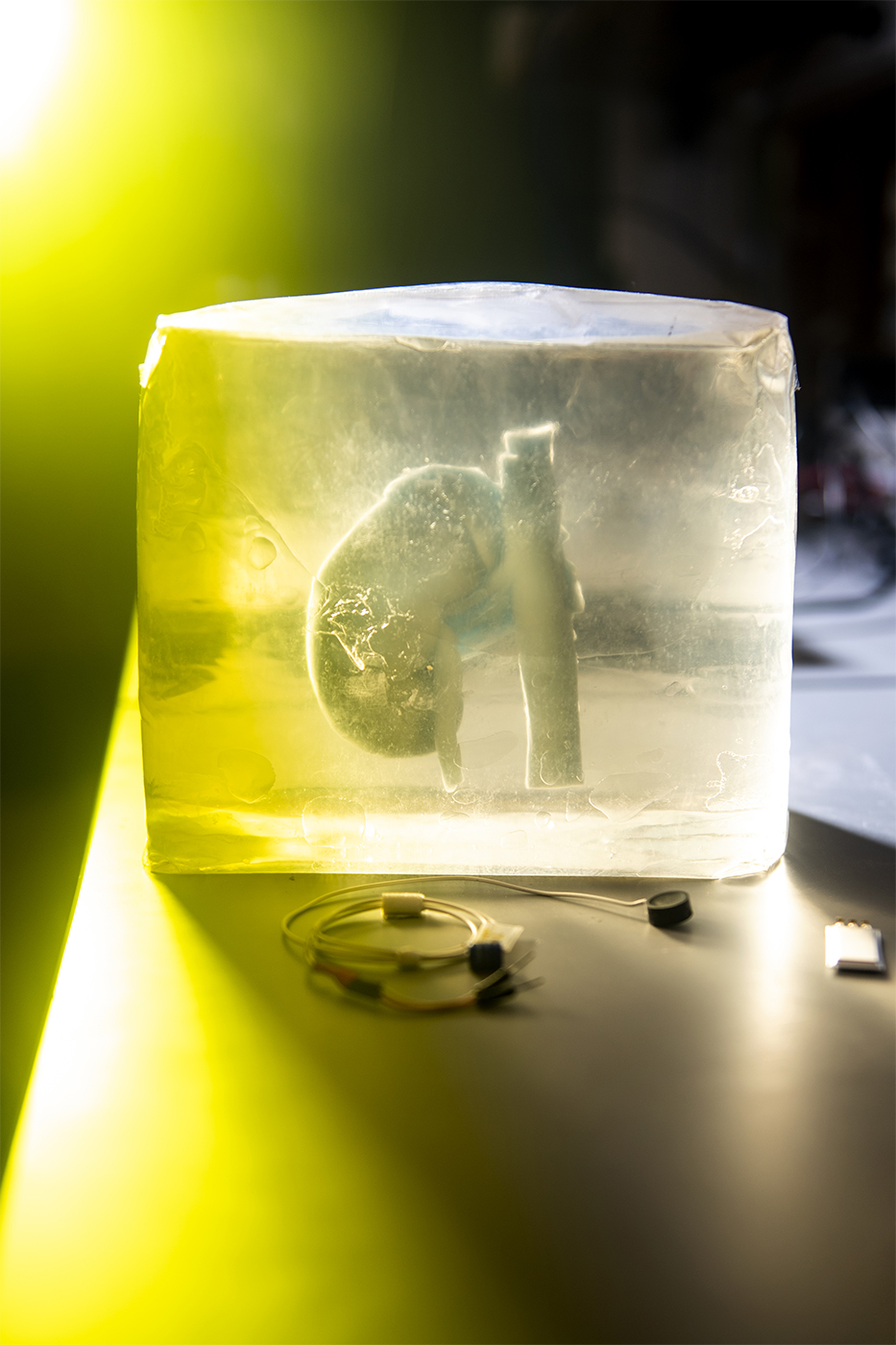

He and his research group hope to begin testing their ultrasonic pacemaker in animal models by the end of the year. The pacemaker would be comprised of multiple implants, each smaller than a dime, that would nestle within the different chambers of the heart and maintain its rhythm through synchronized, invisibly pulsing ribbons of sound. No leads required—and a tiny battery, rechargeable by sound waves from the outside world, would sit under the skin.

Ultrasonic-pacemaker patients would also be less vulnerable to hackers—a surprisingly valid concern, at least for public figures. In 2013, for example, doctors disabled the wireless capabilities of former Vice President Dick Cheney’s pacemaker out of fear that terrorists might hack into him. In contrast, says Melodia, with ultrasonic implantable devices, “[hackers] have to at least touch the person—and chances are you’d notice if someone was touching you—so it’s an additional layer of security.”

Meanwhile, diabetics could someday benefit from a similar system, a wirelessly controlled “artificial pancreas” entirely within the body. An implanted glucose-measuring sensor would continuously send signals to another device: an internal pump that would, in turn, deliver the exact dose of insulin to keep the patient safe.

People with certain neurological conditions could use this technology as well. For instance, Melodia is working to develop a tiny, artificially intelligent chip embedded within brain tissue that could predict incoming seizures and send signals to alert a second device. That second device could then counteract the seizure with carefully calibrated neurostimulation. And Melodia has formed a partnership with a neurosurgeon at the University of Louisville to investigate the possibility of creating lead-less, battery-less deep brain stimulation to treat tremors in people with Parkinson’s disease. “I have no doubt that we’ll do something in that space,” he says.

“If this technology became the basis of miniaturized implantable devices that don’t exist today, it could help save lives,” Melodia adds. He acknowledges that the technology is still being tested in models that mimic human tissues—and while they’ll soon try the implants in animals, testing in humans is likely a long way off. “But we have beautiful prototypes that work great. … The potential is huge.”

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.