Northeastern University graduate Colin Asher writes acclaimed biography of Nelson Algren called Never A Lovely So Real

Nelson Algren was the first winner of the National Book Award for his 1949 masterpiece The Man with the Golden Arm. He was hailed by Ernest Hemingway and others as the leading novelist of the post-World War II era, which led to Algren’s election to the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters a few months before his death in 1981. Today, however, he has been largely forgotten.

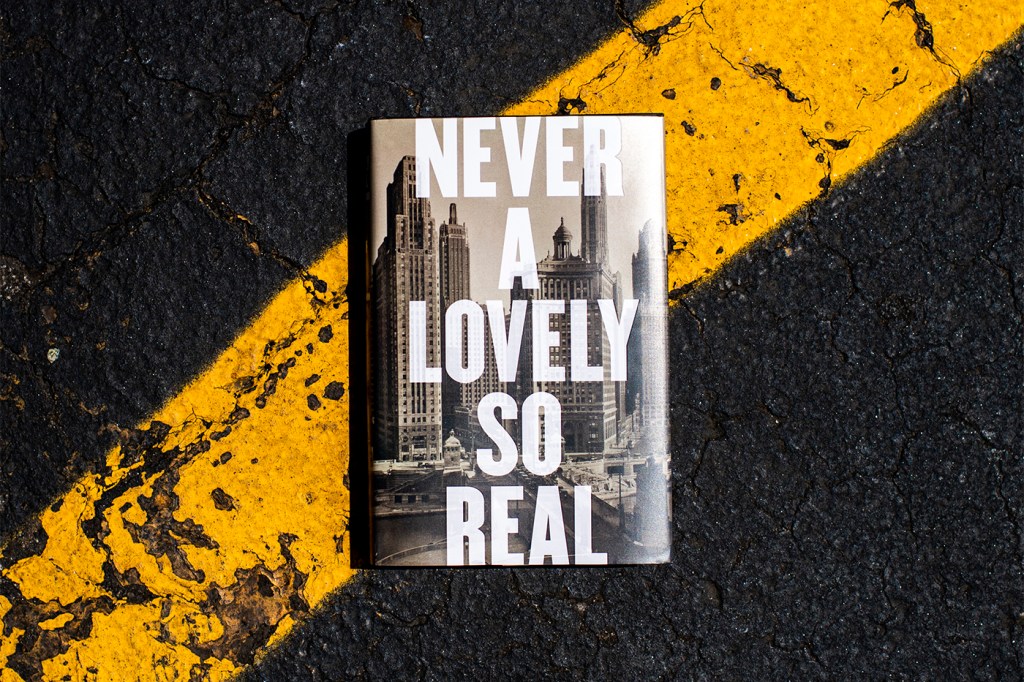

Colin Asher, who graduated from Northeastern in 2009, explores the poignant life of one of America’s great writers in his acclaimed biography Never A Lovely So Real. Photo courtesy of Colin Asher

Colin Asher, who graduated from Northeastern in 2009, explores the poignant life of one of America’s great writers in his acclaimed biography Never A Lovely So Real. It exhumes and makes sense of the influences that elevated and forestalled Algren’s brilliance: His upbringing in Chicago, where he spent most of his 72 years; the Great Depression, which inspired him to tell stories of Americans who had been left behind; and his ties to the Communist Party that stifled his career in the 1950s.

“I had been warned that if you write a biography about somebody, you will end up hating them,” says Asher of his debut book. “That was not what I found.” Asher knew nothing of his subject until he started reading Algren a decade ago in the midst of the Great Recession.

How did you become interested in Nelson Algren?

I had dropped out of high school and spent a long time working before I decided to sign up for community college, and then ultimately to transfer to Northeastern and graduate from there. It was one of the worst periods in American history to be graduating—much like it was for Algren when he finished college in 1931.

It was in that context that I discovered Algren’s work. There were incredible parallels between the things he observed at the beginning of his career, and what I was seeing in America in 2009. He came out of college with a belief in the American Dream—and felt that he had been betrayed by America.

You have said that Algren was “incredibly prophetic.” What were some of the emerging themes of his books?

During the Depression, he immediately starts talking about displacement and poverty and, for a lack of a better phrase, structural inequality.

Nelson Algren in 1956. Photo by Walter Albertin/New York World-Telegram and the Sun

After World War II, he looked to the inner cities and said there’s a group of people being left behind, who feel alienated from all this power and wealth. And I think that is something that we’re dealing with now, right? One of the lessons of the last election is that there is this mass of people in America who no longer see themselves being represented in popular society.

He said that one of the effects of this alienation is that people were receding into drug abuse. There was a morphine epidemic after the war, and he saw this as a manifestation of the capitalist society, of people feeling as if they had become superfluous. And so they were just going to reject society by dropping out.

He also was talking about mass incarceration in the 1940s. As the country was becoming wealthier and more powerful, it was also left with this mass of people who didn’t quite fit into the modern economy, and the way that society dealt with them was by imprisoning them, even if they weren’t particularly a threat and hadn’t particularly done anything.

Algren’s ties to the Communist Party were investigated during the “Red Scare” of the 1950s, when Senator Joseph McCarthy and the House Un-American Activities Committee led the persecution of Americans who were thought to be friendly to the Soviet Union. You uncovered the full extent of the investigation by obtaining the FBI’s files on Algren, who was an outspoken critic of McCarthy. How much was Algren aware that government pressure was forcing publishers to back away from him and therefore stifle his career?

In the broad sense, he certainly knew he was not doing himself any favors by antagonizing McCarthy.

What he didn’t know was the extent of the surveillance—the extent to which the FBI and the local police were in contact with people in his life. And the thing that’s upsetting about that is that he ends up blaming himself. You read his letters from the time, and he is talking about his inability to focus, or about how much he likes his publishers, and how he’s not blaming them for not publishing his books.

He’s not cynical enough to understand what’s happening to him at that point in his life, and it does have these pernicious emotional effects. He never firmly places the responsibility for those things on the government. He has a series of breakdowns, and he attributes them to his financial and marital troubles.

The French writer Simone De Beauvoir met Algren during her 1947 visit to Chicago, which set off a sensationalized, intermittent love affair. What did they share in common?

She came over for a speaking tour not long after the war and she wanted to meet him.

She was connected to the intellectual scene of Paris; he was a guy who was out collecting material in taverns and brothels and police lineups. Her English was imperfect, and his was very colloquial. He had this Chicago drawl that was even difficult for people with neutral American accents to understand.

They really were from completely different worlds, and yet there was this immediate spark, having to do with the fact that they saw the world in similar ways. They shared a love of literature, and there was an immediate physical attraction as well.

Ultimately, Algren was denied a passport [based on the FBI’s ongoing investigation] which prevented him from continuing his relationship with Beauvoir.

Which of Algren’s works is a good starter for those who haven’t read him?

I recommend The Man with the Golden Arm, but the price of admission is high. He modeled it structurally after the Russian authors who he liked the most, so the beginning of the book is a lot of introducing characters and setting themes and setting the tone. I often find people tell me that the first 40 pages are tough to get through. I think that it is the greatest expression of his ethos as a writer.

How is it that someone so famous and accomplished as Algren has been forgotten so quickly?

One thing that was particular to him is that when he had his greatest achievements, he was still relatively uninterested in publicity. He was quiet and mostly focused on his work. After he wins the first National Book Award, he has a name that everybody knows—especially after that novel gets turned into a Frank Sinatra film—but he never tries to capitalize, in part because of the Red Scare, but also because he was interested in just producing more work.

So he had this moment when he could have really cemented himself in the American imagination, but he wasn’t all that interested. And the politics of the times got in the way.

He exceeded expectations, he didn’t expect to be great, and so he had never laid the groundwork to be a huge figure. The other lesson here is just how pernicious the effects of the Red Scare were on the artistic community in the United States. You could be one of the most famous writers in America, and that was not going to save your publishing future.

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.